Bloat in dogs. It’s one of a very few veterinary emergencies where every second matters. As your dog’s biggest advocate, learn the signs, symptoms, causes, and risks associated with this life-threatening medical emergency. Dr. Julie Buzby’s veterinary colleague and friend, Dr. Lauren Blackwelder, shares the facts you need to know about dog bloat.

As a veterinarian, very few things send a shiver down my spine more than receiving a phone call like this one…

“I just got home from work and my dog, Koda, doesn’t seem right. He keeps retching and nothing comes up. He seems agitated and restless. And his stomach is really bloated.”

A few weeks ago, the owner of one of my absolutely favorite Great Danes on the planet left a message like this one. From the moment the phone call came through until the moment Koda’s owner brought him in, I was on edge. Was Koda suffering from GDV (gastric dilatation and volvulus), commonly called bloat in dogs?

As veterinarians, we get numerous calls a week about “pet emergencies” which are not really life-threatening matters, but bloat in dogs is on the short list of “true and urgent” veterinary emergencies. (As an aside, xylitol poisoning in dogs also makes my list of serious veterinary emergencies.)

What is bloat in dogs?

A dog’s stomach is a busy organ. It stretches to accommodate a meal, grinds up the food, and moves it on through to the intestines. It’s constantly expanding and contracting. In some cases, the stomach can stretch beyond its normal means, filling up with huge amounts of food, water, and gas. When this happens, the stomach can twist on itself.

This is a life-threatening emergency for two reasons:

- The twisting not only traps all that gas inside but it can pinch off blood flow to the stomach itself.

- The bloated stomach can also reduce blood flow to the rest of the body by putting pressure on the vena cava (the main vein supplying blood to other vital organs). This can quickly lead to shock.

Therefore, unless they receive emergency veterinary treatment, dogs with GDV (dog bloat) can die within hours.

What are the signs of bloat in dogs?

Just like my veterinary client described, symptoms of bloat can be pretty dramatic:

- Significant abdominal distention (Hence the term “bloat.”)

- Retching—since the entrance to the stomach is “blocked” by the twisting, the dog can’t bring anything up when trying to vomit.

- Restlessness

- Panting

- Drooling

- Abdominal pain

- Pale gums

Usually, these symptoms of bloat begin 2-3 hours after eating, especially a large meal. However, GDV can potentially occur at any time.

It can sometimes be tricky to distinguish signs of bloat from signs of other conditions causing abdominal discomfort. Retching, hunched posture, drooling, and a tense abdomen could also be associated with conditions such as pancreatitis in dogs.

A thorough physical exam and some diagnostic testing will help your vet determine whether your dog has bloat. Any of these signs, particularly in an “at-risk” dog breed, warrant a call to your veterinarian right away.

Is my dog at risk? What factors cause dog bloat?

Technically speaking, any dog can potentially be affected. However, there are some factors that make certain types of dogs at higher risk for GDV.

Large breed dogs, especially deep-chested breeds (sometimes referred to as “barrel-chested” breeds) tend to suffer from bloat more than their smaller counterparts because of their build. There’s just more room for the stomach to “misbehave.”

Statistically, 20% of dogs over 100 pounds will develop bloat.

The following dogs are our “poster children” for this condition:

- Great Danes (42% of Great Danes develop bloat without preventive surgery)

- Irish Setters

- Saint Bernards

- Standard Poodles

- German Shepherds

Additionally, there are other risk factors that can be the cause behind dog bloat. Does your dog check any of these boxes?

- Fast eaters—Dogs who eat fast (looking at you, Labradors!) might be at higher risk for bloat than dogs who take their time with meals.

- Older dogs—Age is a risk factor for bloat too. I love nothing more than the grey-face and soulful eyes of a big old senior pup; however, they are more likely to bloat than younger dogs. This is possibly because the stomach is suspended between the spleen and the liver, and ligaments in the abdomen become more lax with age. This laxity makes it easier for the organs to stretch and allows the bloated stomach the mobility to move and twist on itself.

- Genetics—Ultimately, family history (aka genetics) is the most important risk factor for bloat in dogs. Direct family members of dogs who have bloated are more likely to develop GDV at some point.

Koda, a 7-year-old Great Dane who was, let’s just say, “food motivated,” checked a lot of the boxes for being at risk for bloat. Fortunately, his mom had armed herself with knowledge. She knew his breed was on the “at-risk” list and knew what to watch for.

Her vigilance absolutely saved his life.

How to treat bloat in dogs

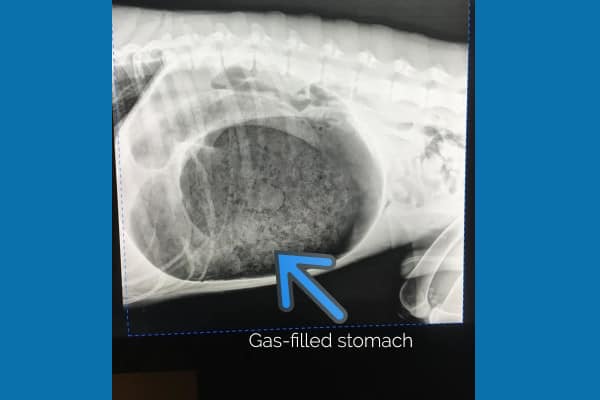

Although it seemed like hours, realistically Koda, my canine patient, was brought through our hospital doors and into the treatment area within about 20 minutes. X-rays and a physical exam confirmed that his stomach was twisted.

The X-rays below show what a dog’s bloated, gas-filled belly looks like…

We all knew time was our enemy.

Surgery for bloat in dogs

Quickly, we placed an IV, started fluids to treat for shock, and prepped Koda for emergency surgery for bloat.

My patient was one of the lucky ones. Although Koda’s stomach was definitely twisted, it still looked healthy.

When the stomach twists, it cuts off the blood vessels that supply the stomach itself. The longer a dog’s stomach is without normal blood flow, the higher the risk for a portion of the stomach to become necrotic, or die. Sometimes parts of the stomach, and even the spleen, have to be removed during surgery if they’ve been deprived of oxygen for too long.

Koda’s stomach was able to be returned to its correct position and appeared normal.

Gastropexy procedure during surgery

Unfortunately, dogs who bloat are at a huge risk of bloating again. That’s why a veterinarian typically performs a procedure called a gastropexy after untwisting the stomach during GDV surgery. This involves permanently tacking the stomach to the inside of the body wall. That way, if the stomach ever overfills with gas again, it is seated in place and cannot twist on itself.

In dogs with bloat, the most danger lies in the twisting, because blood flow is interrupted.

How can you prevent bloat in dogs?

The most effective way to prevent GDV is a prophylactic gastropexy. In high-risk dogs, there is no need to wait until they bloat to tack their stomachs. A prophylactic gastropexy is a surgery where the stomach is permanently sutured to the body wall to prevent it from flipping if it ever bloats.

If you’re worried about your dog’s risk for GDV, talk to your veterinarian about this procedure. Oftentimes, the procedure can be performed at the same time as a spay or neuter. Plus, there are minimally invasive techniques that can make it a relatively simple surgery.

A few weeks after Koda recovered from his ordeal, his mom brought his sister, Scout, to see me. Remember—having a close relative that has bloated is the main risk factor for GDV, and Koda’s owner did not want Scout to go through it too. We were able to get Scout in for a prophylactic gastropexy (much less stressful than an emergency one!) and she recovered beautifully.

Do elevated dog food bowls or slow feeders help prevent bloat?

Many concerned dog owners ask me about the effectiveness of elevating the dog’s food bowl as a way to prevent bloat in dogs. While this used to be commonly recommended to prevent GDV, more recent studies have actually disproven its effectiveness.

The best study we have available showed that elevating food and water bowls was actually associated with an INCREASED risk for GDV. (It’s important to mention that elevated food and water bowls can be beneficial for other medical conditions in aging dogs. For more information, read 7 Senior Dog Care Tips.)

Slow feeder bowls and feeding strategies to help prevent bloat in dogs

Since dogs who eat too quickly may bloat more frequently, trying a slow feeder bowl is a good option. Slow feeder bowls are specially designed, sort of like a little puzzle the dog has to solve in order to get to the kibble. This exercises a dog’s mind and slows down food intake!

Another feeding strategy to consider is the number of meals per day. Dogs who are fed only once per day are more likely to bloat. Splitting feedings into two or three smaller meals per day is proven to lower the incidence of GDV.

The bottom line on bloat in dogs

As I mentioned, Koda is one of the lucky ones. First, he has a knowledgeable owner who recognized his signs of distress and sought emergency medical treatment right away. Second, we were able to untwist his stomach before any permanent damage had been done. Third, he didn’t suffer any ill effects from shock or heart arrhythmias that can go along with this condition.

Ultimately, even with prompt treatment, bloat in dogs carries a 10-30% mortality rate. If you notice any signs of distress like retching, restlessness, and abdominal distention in your dog, call your vet right away. And if you are the parent of a higher risk dog breed, talk to your vet about ways you may be able to reduce the risk of this happening to your dog.

What questions do you have about bloat in dogs?

Please comment below.

A week ago I lost my 29 month old female GSD. 4 hours after her evening meal around 9:30 (she is fed 3 times per day) she vomited mushy partially digested food 3 times, drank water and vomited again. She was a pacer and anxious by times so her being restless checking the other dogs kennels for food etc was not unusual. I checked her abdomen which was soft I listened with a stethoscope to gurgle normal bowel sounds she did not pull away, whimper or react like she was in pain. She settled, and then about 11 went out for a bowel movement which was soft and had some mucous in it. She drank some water and kept it down. Around midnight she was wanting to go out again and I was thinking she may have diarrhea so out she went she was straining to go then went in a jog around the property and laid down in the snow. My husband went out to bring in her because she was ignoring me per usual and noticed a large pile of stool on the ground a short distance away from where she was. When she saw him she jumped up tail wagging and trotted into the house. A short time after she came into the kitchen acting kinda panicky wanting out then went into her kennel. On the floor there were three spots of blood and she had blood around her rectum. Once again I checked her. Breathing & were Pulse, normal and her gums pink and warm. I cleaned up her rectal area and noted some smeard stool and bright red blood.. she then went into the bathroom had a drink and stretched out on the heated floor. She was resting quietly so we thought she my have passed the large stool pile my husband saw and has tore it possibly had a hemorrhoid. By 2pm we were on the way to the emergency vet as I checked her again and she was bloated, breathing shallow cool pale gums and her pulse was fast. Xrays showed air in her stomach and entire intestinal tract. The X-rays were not typical of GDV and there was no obvious intestinal blockage just her entire system filled with gas. There was still bright bleeding from her rectum but not gushing or anything just a small amount of seepage. Unfortunately she was too compromised to survive surgery and we held her and chose a pain free passing surrounded by love and heartbreak. 12 days before her death we had a complete check up and thorough blood work with every test coming back normal. She had puppies in August a large litter and was not back in condition so wanted to ensure she was healthy thus the 6 pages of blood work. The vet thinks it was GDV with AHG and it simply over whelmed her. Tests and X-rays were sent to our vet who along with the emerge vet agreed it was not a genetic disorder so we opted not to have an autopsy although I am racked with guilt and wish we had gotten it done.. what does this scenario sound like to you?

Dear Terry,

I am so sorry for the tragic loss of your beloved girl. Honestly, I am just as puzzled as to what could have caused these severe symptoms as you. I have never seen hemorrhagic gastritis and GDV occur at the same time but that doesn’t mean it isn’t possible. Is there any possibility your girl could have come across something toxic or poisonous? While you may never know the exact cause, I do think you made the most loving choice to free her from her suffering and offer peace and rest. May her memory be with you always and continue to be a blessing in your life. Wishing you comfort and healing for your heart.

Could a breathing problem in dogs cause bloat?

Hi Sammy,

Not typically, but I guess it is possible. If a dog is swallowing lots of air and the air becomes trapped in the stomach, then it may be able to progress to bloat.