Lyme disease in dogs is easily contracted and can cause an array of symptoms. If you live in an area with ticks, you should arm yourself with knowledge of what this disease looks like and how to prevent it. Integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby breaks down 10 facts about Lyme disease in dogs—including information about dog Lyme disease vaccines.

After coming in from the yard, you notice a tick attached to your dog behind his ear. Instant anxiety. How long has that tick been there? Could the tick carry diseases? What should you do next?

In a previous post, we discussed tick-borne diseases in dogs and what you can do to limit your dog’s exposure. While ticks can transmit many diseases, Lyme disease in dogs is the one that I worry about most.

Whether you live in a Lyme endemic area or not, Lyme disease should be on your radar. My dog loves frolicking through tall grass and hiking. I am always keeping a close eye on his exposure to ticks, and doing what I can to reduce risk.

If Lyme is prevalent in your region, both your dog and your family are at risk. If Lyme is not prevalent in your area, it may only be a matter of time until it is.

Let’s take a look at ten facts about Lyme disease every dog parent needs to know.

1. Dogs all over the world contract Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is not just a U.S. problem. Variants of Lyme have spread into Canada and Europe. This is possibly due to migratory birds carrying the infected ticks to far-off places and across the ocean.

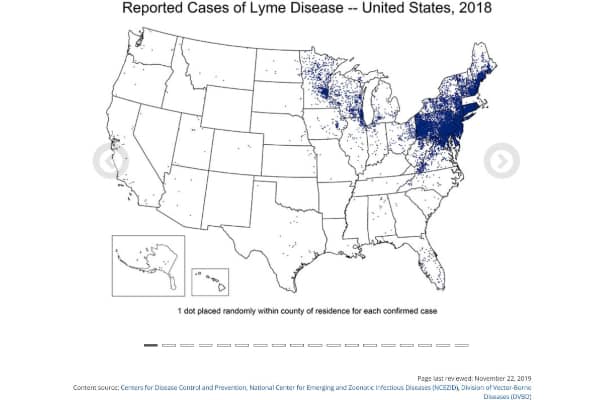

Lyme is named for Lyme, Connecticut. While we typically think of the northeast and upper midwest as being a hotbed for Lyme cases, every state in the country has reported documented cases.

People may mistakenly assume they are safe from Lyme based on geography. Sadly, nothing could be further from the truth for both dogs and their human owners.

I’ve even heard cases of missed diagnoses in humans because Lyme is not considered endemic in their geographic areas. The reality is that Lyme is rapidly becoming a serious problem throughout the United States and worldwide. Just because you’re in an area without a lot of cases of Lyme disease doesn’t mean it can be ruled out as a possibility.

Lyme disease in dogs: The statistics

The Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) is a non-profit organization dedicated to reducing the number of parasites in dogs and cats, as well as reducing the risk of transmitting these parasites and diseases to humans. It is my go-to resource for information about parasites of all kinds.

Based on research from the CAPC, there are around 915,000 antibody-positive Lyme disease tests in dogs annually. Let that sink in. There are almost a million positive Lyme tests in dogs every year!

2. Lyme disease exposure in dogs is cheap and easy to diagnose.

What do I mean by “Lyme disease exposure”? I say exposure here because the tests vets routinely use to “diagnose” Lyme disease actually detect antibodies in dogs, proving that they have been exposed to natural Lyme infection and their immune system has responded. However, most of these dogs are asymptomatic—up to 90% will never develop clinical signs.

While that is great news, recognizing that a patient has been exposed is super helpful to me in caring for their health (present and future). One of the reasons is that dogs with Lyme disease can develop joint inflammation and arthritis that is not readily apparent. Knowing a dog has tested Lyme positive puts me on guard to be hyper-vigilant about subtle clinical signs of Lyme.

Dog Lyme test

In veterinary medicine, we are lucky to have options for in-house Lyme testing. These inexpensive tests are run with just a few drops of your dog’s blood. And the results are ready within minutes. Many veterinary hospitals carry combination tests. They test for heartworm disease in dogs, Lyme, and other tick-borne diseases. I recommend these tests yearly for most of my patients.

Additional tests, such as one which measures the dog’s antibody levels to a special peptide (C6), are great tools for veterinarians seeking to diagnose and track Lyme-positive patients.

Incidentally, these tests are not available for humans. So the road to a human diagnosis is often more complicated.

3. Symptoms of Lyme disease in dogs can be very serious.

The most common presentation of Lyme in dogs is subclinical infection. This means a dog will test positive without showing any signs. Clinical signs only develop in 5-10% of infected dogs, but they can be very serious.

Signs of Lyme disease in dogs include:

- Fever (as high as 103+ degrees)

- Joint inflammation and pain

- Shifting leg lameness (intermittent limping that moves from leg to leg)

- Lethargy in dogs

- Loss of appetite/not eating

- Swollen lymph nodes

4. Dogs can develop a life-threatening complication called Lyme nephritis.

A small percentage of dogs (1-5%) who test positive for Lyme go on to develop a condition called Lyme nephritis—inflammation of the kidneys. However, this is a unique kind of kidney insult that we believe is related to the way the immune system fights the disease, which causes damage to the kidneys.

Sadly, the prognosis (expected outcome) for dogs that develop Lyme nephritis is not good. These cases often end in euthanasia because dogs can go into sudden, progressive, renal failure. This is most commonly seen in Labrador and Golden Retrievers. But we do not know if this is a true breed-specific statistic or if it’s just that those are the most popular breeds of dogs living at-risk lifestyles and, therefore, are overrepresented.

Even if “classic” Lyme nephritis is not diagnosed, one research study reported that dogs who tested positive for Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria that causes Lyme disease) exposure had a 43% increased risk of later developing some form of chronic kidney disease. This is an intimidating statistic that should motivate any dog owner to take tick control seriously. And, for dogs who are at risk, vaccinate for Lyme disease.

It’s also why, as a veterinarian, I closely monitor a Lyme-positive dog’s blood tests and urinalysis regularly. Although only a small percentage of Lyme-positive dogs will develop Lyme nephritis, I want to make sure to catch it early if it happens.

5. Lyme is not transmitted animal-to-animal.

Lyme is vector-borne, meaning it is spread through tick bites, specifically by deer ticks and black-legged ticks. Once Lyme infects your dog, your furry companion cannot transmit it directly to other animals or people.

However, if your dog is positive, you are also at risk because you and your dog live and play in the same places. So if your dog tests positive, it’s a red flag to indicate that you should be concerned about exposure for you and your family as well.

If you are experiencing symptoms of the human form of Lyme disease, make an appointment to talk with your doctor as soon as possible.

6. You don’t have to see a tick to get Lyme disease.

You may be wondering, “How can I get Lyme disease if I never see a tick on my body?”

Unfortunately, people often don’t see the tick, but it happens—just look at the thousands of cases diagnosed annually in the U.S. About 30,000 cases each year are reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; however, the majority of Lyme diagnoses go unreported. It is estimated that 300,000 people contract Lyme disease each year.

This data can be extrapolated to dogs. Ticks are very good at hiding in fur and in biological crevasses like between dogs’ toes.

A painless tick bite

One of the reasons ticks may go unnoticed is that tick bites are painless. There’s usually no significant irritation right away. Later, inflammation is common at the site of attachment. Tick bites fly under the radar of the body’s defenses.

The 48-hour window of tick-borne disease transmission

It is thought that ticks need to feed for 36-48 hours to transmit Lyme disease. This is why I stress that you need to frequently check yourself and your pets for ticks—particularly after you’ve been in a high-risk area like grassy fields or woods.

Timing matters immensely. If you remove a tick that has only been attached for a few hours, there’s little chance of tick-borne disease transmission.

This is also how many tick-preventative products work to protect against tick-borne diseases. Usually, the products will cause the tick to die or fall off shortly after it bites—well before the 48-hour mark.

Just because you’ve never seen a tick on your dog does not mean that he or she cannot have contracted Lyme disease. Most of the time we never see the tick that transmits the disease.

7. Lyme disease presents differently in dogs than people.

When you hear the words “Lyme disease,” perhaps the thing that pops into your mind is the classic red bullseye rash.

The scientific name for this “bullseye rash” is erythema migrans. Since a dog’s hair hides the rash, it’s common to miss seeing it.

If you do see a rash on your dog, it will continue to grow because the bacteria, which are called spirochetes (and look like little corkscrews), are literally screwing themselves through the tissue. At some point (scientists aren’t sure when or why), the bacteria stop disseminating through the skin, turn, and go into the rest of the body—the joints and the nervous system. Really, no body system is off-limits.

However, Lyme disease symptoms and the progression of those symptoms are quite different between dogs and people.

According to Dr. Wendy Brooks of the Veterinary Information Network, “After being bitten by a tick that has transmitted Borrelia burgdorferi, 80 percent of humans will develop a rash and/or flu-like symptoms. In the next few weeks, joint pain ensues with 15% of people developing neurologic abnormalities associated with Lyme disease and 5% of people developing a heart rhythm disturbance… At this same point in the infection timeline, dogs have yet to develop any symptoms at all and 90% of infected dogs never will.”

While this is great news for dogs, don’t let your guard down. Dogs who manifest clinical signs are sick, painful dogs, and only a small percent develop Lyme nephritis.

8. Dogs with Lyme disease are not protected against future Lyme disease.

Unfortunately, unlike some other diseases, infection with Lyme does not create protective immunity. That means a dog can contract Lyme disease more than once.

Therefore, if your dog has tested positive for Lyme disease in the past, you are not off the hook. We still need to take precautions to protect your dog against another Lyme infection.

9. There is a vaccination for Lyme disease in dogs.

Although there’s currently no Lyme vaccine on the market for humans, there are several vaccinations available for Lyme disease in dogs.

Whether to recommend the Lyme vaccine to dogs is a bit of a contentious debate in veterinary medicine. The Lyme vaccine is not currently considered a “core” vaccination. Core vaccines, such as Rabies and distemper/parvo vaccinations are ones that are recommended for all dogs regardless of lifestyle risk.

Does my dog need a Lyme vaccine?

The fact that the Lyme vaccine is not a core vaccine does not mean that it is not safe or that dogs should not be vaccinated for Lyme. It simply means that, at this point, there isn’t enough evidence to recommend the vaccine for all dogs.

Reasons for this selective recommendation include:

- Lyme is less common in some geographic areas

- A vast majority of dogs who test positive for Lyme do not get sick

- Tick preventions, if used correctly and consistently, do a good job of preventing tick-borne illness

- Most dogs who get sick from Lyme disease (with the exception of those rare cases of Lyme nephritis) respond well to antibiotic treatment

With these considerations in mind, we (veterinarians and dog owners) must make judgment calls on an individual basis as to whether to vaccinate a dog for Lyme.

Would I recommend the Lyme vaccine for a Maltese dog in Colorado who is pottying on a pee pad and rarely leaves the house? Probably not. Would I recommend the Lyme vaccine for a Labrador Retriever dog in Connecticut who spends every weekend hiking and camping with his owner? Absolutely.

Remember: Even if your dog is vaccinated for Lyme, that does NOT mean that you should slack on tick prevention! We want to employ every bit of protection for dogs that we can, and Lyme is not the only disease that ticks can transmit!

10. Your vet is your best ally for preventing Lyme disease in your dog.

I encourage you to talk with your veterinarian about your dog’s Lyme risk. I would never want to recommend something different than what your vet believes to be best for your dog. If your dog’s next wellness visit is coming up, why not ask your vet about Lyme disease in dogs? Together, you and your vet can determine whether your dog needs the Lyme vaccine.

Also, don’t forget to tell your vet about travel plans that include your dog. Especially with diseases such as Lyme, risk can be affected by geography. If you live in a low-risk area but are traveling with your dog to an area with more Lyme, your vet’s recommendation about vaccinating your dog may change.

Don’t forget to talk with your vet not only about the Lyme vaccine but also about which parasite preventions he or she recommends to keep your dog safe from a whole host of illnesses!

Hope for a world without Lyme disease in dogs—and people

I’m delighted and grateful that scientists, veterinarians, and doctors are making progress in the fight against Lyme.

I hope that in the next decade, the same technology we’re using for Lyme vaccination in dogs will be available and effective in people. I truly believe the stage is set. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if, in just a few short years, Lyme disease is an illness of the past for both dogs and humans?

Have you had firsthand experience with Lyme disease in dogs?

Please share your dog’s story in the comments below. We’d love to hear how you’ve faced—and overcome—the all-too-common illness.

Hi Everyone, My pup Grover was a rescue in Ky. He had been dumped at a Truck Stop 3 months prior to me being tagged to his rescue . After 2 weeks and 5 hours each day. I was able to get him. I gave him bravecto before I rescued. Just in case. My vet said ticks dead. But Grover had Ticks not familar for Ky. SC yes .. After 3 months at the vet. He was determined to be in remission at the age of 5. Had to remain calm. we did so for the next 8 years. Then areas around us got hit by Toronados. Friend 🧡 needed temp foster with her pup. Sure no – biggy. But Grover got stressed. Now having Night Mares . Lots of panting . Still eats , No Bathroom issues . I dont want to stress him out again . But could have a possible 13 year old coming to live with us. Not sure what to do. He is my #1 priority. Any advise ? Thank you ♥️ 😊 🙏

Hi Ange,

It sounds like Grover has been through a lot and he is very lucky to have found you when he did. Forgive me for asking, but what are you needing advice about? I was a bit confused after reading your post. Are you worried about a relapse of the Lyme Disease? Are you looking for ways to help reduce stress or keep him calm? Is it the nighttime anxiety that has you most concerned? Hoping you can find the answers you are looking for and ensure your sweet boy has many happy years ahead. Bless you both.

Our mixed breed cocker spaniel/husky/beagle was diagnosed at age 10 with Lyme. He was 1 of 8 puppies in an ALL MALE litter, and he looked like a mini golden retriever. The other 7 puppies varied in size, color, fur type, and physical features. Dusty was the only one of the 8 who got the long hair trait, and although it was the slightly curly signature spaniel trait, the density of the fur was more like a husky. Finding a tick on him is practically impossible given the amount of his thick, incredibly long fur. We treat him regularly for tick prevention. Our first indication that something was wrong was overnight he went from being his normal and active self, to being unable to stand at all. His body was shaking, he had a fever and I didn’t know what happened. He wouldn’t move his legs at all and I worried he may have had a stroke overnight. I rushed him to the vet, they did multiple tests including the lyme antibody and they said his kidney function was slightly lower than they’d like to see, but it was a very minor margin. They treated him for Lyme with Doxycycline, and within a day he was almost back to his normal self, but we continued the course of treatment for a full 4 weeks. I had to take him back to get another kidney function test and it hadn’t changed. That was encouraging news, considering the known effects of Lyme on the kidneys. He’s had 2 visits with the vet since then, and his kidneys hadn’t shown any alarming levels of change, his last check up was in March 2023. He never gained all of his energy back, but I’d say he got to maybe 90%. He was happy, and seemingly healthy. Dusty turned 12 in October 2023. The first week of November we found him once again, just overnight, unable to stand, he had a fever, and he was shaking. I rushed him to the vet, and as I suspected it was from Lyme again. This time his kidneys had shown a little more change than she’d like to see, especially because he was symptomatic again. She told me that at age 12, recurring lyme disease and the decline in kidney function since March, she couldn’t promise that his level of recovery would be what we saw last time. He wasn’t in kidney failure yet, but warned us that it was something that could happen if it wasn’t caught in time. She started another 4 weeks of Doxycycline treatment again and just like before, we had our boy up and walking, doing stairs within a couple days and he slowly improved over those next 4 weeks, but it wasn’t the same level or pace of recovery as the first time. We had constant contact with the vet, she wanted to be sure he wasn’t experiencing a change in urination throughout the last month. His 4 weeks of treatment ended last week, and he was supposed to go back for a visit this Monday. Our vet is retiring and her clients are in the process of finding alternative offices to continue care. Her office is currently doing basic comprehensive testing and care during the transition, no surgeries, and no emergency care. On the morning of December 16th 2023, our son woke up first and was going to take Dusty out to go to the bathroom and he wouldn’t come out of his crate. His breathing was somewhat labored, he was trembling, he was drenched as if he had been sweating profusely, and I knew immediately that it was very bad. I called the animal hospital she recommended in case of emergency and they said to bring him right away, even though it is an hour drive. My husband helped me get his crate into the van and I left with him right away. Our kids knew deep down that I’d have to make some really tough decisions based on whatever the emergency vet said. Dusty has always done well at the vet, he’s not anxious or afraid. The doctor who came in to see Dusty was fantastic. He got right down to Dusty’s level, he gave him some good ear rubs, he talked with him like he was an old friend coming to visit, and not just another dog that came in through the door. He very subtly was performing an exam by engaging in normal dog/human interactions, like “can you shake? Good boy!”, and getting almost nose to nose with him and “look at those big beautiful eyes, you’re such a sweet boy!”. Each thing was to check a medical component, but to Dusty it was just love and attention. He was checking for nervous reflexes, and how his eyes responded to light. He was feeling his joints, and checking his muscle tone. He asked me some questions to get an overall picture and timeline of his Lyme history. I explained it all, and answered his questions. The doctor told me he was very concerned that the Lyme disease had effected his central nervous system as well as his kidneys. He was lacking some of the basic reflexes that aren’t usually accompanied with the rigidity of symptomatic Lyme. His eye response to light was abnormal, his heart rate was very high, even though he wasn’t very active, and his breathing was irregular. He could tell Dusty was trying to wag his tail with all the attention but it took all his energy and he’d eventually breathe in deep and then sigh. He told me he could try to put Dusty on something other than the Doxycycline, to see of it made a difference in his mobility, and that it may give us a little more time, but he wasn’t confident that the overall outcome would change. He left the decision up to me, and I told him I wanted to do what was best for my sweet boy. It would be cruel to make him suffer just to give us a few more weeks with him. It would be harder on my kids too. We could all see that he was definitely suffering. I made the decision to keep him from suffering anymore. We’ve had more than 12 wonderful years with him. He was born in our home, and we have gotten to love him every single moment of his life. He’s always been by our side, trying to make us feel better when we’re having a rough day and we owe it to him to let him pass in peace, not in pain. It was hard, but it was the right thing to do.

Dear Amy,

Your words have truly touched by heart. It is clear Dusty was dearly loved and such a vital part of your family. I am sorry his health declined so suddenly and left you having to make this difficult decision. I agree, saying goodbye was the most loving option and only way to give your sweet boy peace and freedom from his suffering. I hope with time your heart will heal and your family will be comforted knowing Dusty lived a wonderful life. May his memory live on and be a source of joy as you continue life’s journey. ♥

My dog was diagnosed with probable SLE (Lupus) in July after a mysterious illness, which was put into remission with Prednisone. He had weaned down to 5mg Prednisone per day when he was bit by a tick. I sent the tick for testing, it was an adult female deer tick, positive for the bacteria that causes Lyme, attached for 100 hours. I’ll get him tested for Lyme soon (at 30 days after the tick was removed). How might Lyme disease interact with Lupus and Prednisone?

Hi Mary,

I am sorry your pup has been through so much over the last few months. It is hard to know for sure how two different disease process with affect each other. I would be worried about the immune system becoming stimulated and think you should be monitoring for a possible lupus flare. Hopefully you can get the test results soon and start the appropriate treatment if needed. Feel free to leave an update as new information comes to light. Best wishes and good luck!

My dog tests positive pretty much every time he goes to the vet plus another tick borne infection. His ab levels are pretty high. This is in spite of routine vaccinations and flea and tick treatment. I’m in NJ and deer ticks are everywhere. I haven’t been able to get a urine specimen as requested despite trying. He has no overt symptoms of kidney disease. My vet typically gives him a round of antibiotics. Is that necessary in an otherwise healthy animal. What’s the recommendation for a situation such as this?

Hi AJ,

I am glad your dog hasn’t had any kidney changes and no symptoms of the disease are apparent at this time. There are no specific guidelines whether to treat an asymptomatic dog or not. Most of it is veterinarian preference. Your vet is probably trying their best to keep the infection dormant, so your pup doesn’t have to deal with painful symptoms. If you want an expert opinion or still have lingering questions, my best advice would be to schedule a consult with a specialist. They can let you know if other treatments should be pursued or if yearly routine monitoring is best.

How potent is the first dose of the boehringer Lyme vax given to a dog? How long is it effective?

Hi C.B.,

Every Lyme vaccine that is currently approved for use requires a second “booster” vaccine to be administered about 3 weeks after the first dose. Without this second dose of vaccine, the immune system is not properly stimulated, and the dog is not fully protected.

Can the lyme vaccine cause kidney disease/failure in dogs?

Hi M,

Kidney failure is not something I would normally be concerned with when vaccinating a dog for Lyme. As with any medication or vaccine, there is always the potential for an adverse reaction. This is why each dog’s individual risk factors for Lyme should be carefully weighed to determine if the vaccine is a good choice.