“Do dogs have knees?” is a fairly common question among dog parents. The short answer is—yes! But we don’t plan to stop there. Integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby dives into canine anatomy to answer that question in more detail and explains some common knee problems in dogs.

You’ve probably seen entertaining photos of dog parents who resemble their dogs. Dogs and their humans do share a lot in common! Of course, dogs are obviously built differently than we are, but we do share some anatomical traits.

Which brings me to a couple of questions that I get a lot from curious dog parents about their pups’ bodies: “Do dogs have knees?” and “Do dogs have knee caps?”

In short, yes, dogs do have knees. They have two knees, two knee caps, two elbows, two wrists – just like us! Let’s take a look at some canine anatomy.

“Do dogs have knees?” and other anatomy questions answered

Dogs have the same bones and joints we have in our arms and legs. However, these bones and joints have different functionality in dogs since they walk on four legs and we walk on two.

Starting from the bottom up, dogs have digits, just like we have fingers and toes. Their “thumb” is the dewclaw, and the remaining four toes are numbered 2 through 5 from medial to lateral (i.e. inside to outside of the paw).

Unlike humans, the part of dogs’ feet that touch the ground (i.e. the weight bearing surface) is primarily these digits. Essentially, dogs are walking on their toes.

Dogs’ hind legs do have metatarsal bones, just like we have in our feet. However, they do not touch the ground the way ours do. This is somewhat comparable to us walking on tip-toe. The anatomy is similar in the front legs. The toes or digits are what dogs walk on and the metacarpal bones go up the leg. In contrast to dogs, human metacarpal bones are what we have in our palms.

Leg anatomy

Moving up the dog’s leg from the toes, we can follow the metatarsal and metacarpal bones to the ankles and wrists. Yes, dogs do have ankles and wrists! In dogs, the ankle joint is referred to as the hock or tarsus, and the wrist joint is the carpus.

Dogs also have two knees and two elbows. The bones above the carpus in dogs are the same as in human arms—the radius and ulna. These bones make up the forearm. The elbows are located at the upper ends of these bones. In the hind leg, the tibia and fibula extend from the hock to the knee (i.e. stifle). Above the elbow is the humerus, and above the stifle is the femur—the same bones that make up our upper arms and thighs.

What bones and structures make up a dog’s knees?

Dogs’ knees have many of the same structures as ours. The tibia/fibula and femur create a hinge joint where they meet. Ligaments and muscles are responsible for holding the joint together. If you feel the front of your dog’s knee, you should feel a small bump of a bone. This is his or her kneecap (i.e. patella). The patella is a small bone that provides an anchor for the quadriceps muscles of the thigh via the patellar ligament. The ligament attaches to the front part of the tibia and pulls the leg straight as the quadriceps contract.

There are also important structures inside the joint capsule, which is behind the patella. The meniscus, a layer of thick cartilage, covers the end-on surfaces of the femur and tibia. This cartilage lubricates the joint, acts as a sort of shock absorber, and helps facilitate pain-free movement.

The ligaments of the knee

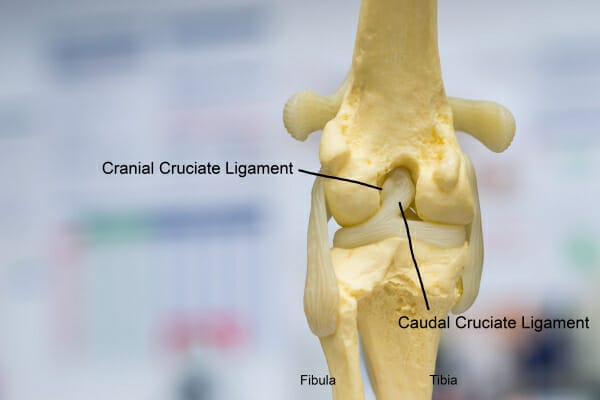

Inside the knee joint are two very important ligaments that criss-cross between the femur and tibia called the cruciate ligaments. In humans, these are referred to as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). Since we stand upright, our anatomical directional terms are slightly different than the ones we use for dogs.

As such, these same structures in dogs’ legs are called the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL or CrCL) and caudal cruciate ligament (CaCL). These ligaments stabilize the knee to prevent the tibia from moving forward and backward in relation to the femur. “Drawer” is the term for this movement. You may have heard of a drawer sign test. It is the way veterinarians and physicians assess the integrity of the cruciate ligaments.

The medial and lateral collateral ligaments run down the sides of the knee. They stabilize the joint from the outside, preventing too much sideways movement, and keeping the hinge function of the joint on track.

What are some common knee problems in dogs?

Unfortunately, knee issues in dogs are quite common. There are two broad categories these problems typically fall under—congenital issues (i.e. those present from birth) and knee injuries.

Patellar luxation

Medial patellar luxation (MPL) is typically a congenital issue that primarily affects small and toy breed dogs, such as Yorkies, Pomeranians, Chihuahuas, etc. In this condition, the kneecap slips out of place toward the inside of the leg. It may or may not spontaneously correct depending on the severity of the condition. Patellar luxation most commonly presents as dogs “skipping a step” or intermittently holding up the affected leg(s) when walking or running.

Dogs can also suffer from lateral patellar luxation (LPL) where the kneecap moves to the outside of the leg. This is more often the result of an injury rather than being a congenital issue like MPL.

Your veterinarian can diagnose a patellar luxation based on the physical exam and imaging such as an X-ray. Depending on the severity, your veterinarian may recommend medical or surgical treatment.

Cruciate ligament tear

A CCL tear (otherwise known as a torn ACL in dogs) is one of the most common orthopedic injuries I see. It typically happens in larger breed dogs such as Labs, German Shepherds, and Pit Bulls. They may have a partial or full tear. You may have heard of athletes suffering from ACL tears—this is the same injury for dogs.

However, it doesn’t always happen in exactly the same manner. Athletes tend to rupture their ACL suddenly. On the other hand, dogs may have hidden degeneration of the CCL that predisposes it to rupture. As such, it may look like the dog acutely tore the CCL running, jumping, playing fetch, etc. but in reality the stage had been set for that injury for a long time.

Similar to patellar luxation, the veterinarian can usually diagnose a CCL tear with physical exam, the drawer test, and X-rays or other imaging. Treatment may depend on the individual dog’s situation, but typically a surgical procedure such as TPLO surgery for dogs gives the best outcome.

Meniscal tear

Just like people, dogs can have tears in their menisci from trauma of some sort. Landing wrong after jumping up to catch a frisbee may be enough to damage the sensitive knee cartilage. Meniscal tears are also very commonly associated with CCL tears. Cartilage is very difficult to assess on X-rays, so advanced imaging like MRI or arthroscopy in dogs (scoping the joint with a small camera under anesthesia) may be necessary to make a diagnosis. The veterinarian may recommend medical or surgical treatment for meniscal tears.

Collateral ligament tear

The collateral ligaments on the sides of the knee can be injured as well. However, this type of injury is far less common than a CCL tear. It could result from an injury such as another dog crashing into a dog’s knee during play. Additionally, the collateral ligament could tear due to significant trauma to the knee (i.e. a fall, dog fight, or being hit by a car). In these cases, the damage often involves several knee structures.

As with the other orthopedic problems, the veterinarian can often diagnose a collateral ligament tear on a physical exam and imaging. Treatment depends on the severity and effect of the tear but may involve medical or surgical therapy.

Fractures

Just like any other bones, the bones of the knee can also break. Outside of an underlying health issue such as a bone tumor, this would require significant trauma. Your veterinarian can diagnose a fracture on X-rays. Due to the location, a cast or splint is rarely effective. Thus, surgical repair is typically the treatment of choice.

How can I help my dog who has a knee injury?

Realizing your dog may have a knee injury can be distressing and leave you wondering what to do. First, taking your dog to the vet promptly is the most important thing you can do. This will not only get you closer to a diagnosis, but your vet can provide any necessary pain relief for your pup.

It’s important to remember that many human over-the-counter pain relievers are toxic to our dogs. The answer to the question “Can I give my dog Advil” is “No!” so please don’t give your dog anything from your medicine cabinet without consulting a vet first!

Depending on what’s going on with your dog, your vet will make recommendations to help. Veterinary medicine has come so far, and we have many options available to help our furry friends! Options may include:

- Referral to a veterinary orthopedic specialist

- Surgery (performed by your family veterinarian or an orthopedic specialist)

- Prescription pain medication like NSAIDs, tramadol for dogs, or gabapentin for dogs

- Weight loss to take pressure off joints (find your dog’s body condition score to determine if he or she may need to lose weight)

- Acupuncture

- Laser therapy for dogs

- Physical therapy

- Joint supplements for dogs like Dr. Buzby’s Encore Mobility™ hip and joint supplement

- Prescription diets to improve joint health or aid in weight loss

- Traction aids like non-slip mats or, even better, Dr. Buzby’s ToeGrips® dog nail grips

- A period of activity restriction to facilitate healing

Your veterinarian will tailor the treatment recommendations to your dog and his or her specific condition. But as always, don’t forget to add in your own regimen of therapeutic snuggles!

Yes, dogs have knees!

I hope that in reading this article, you have gained a better appreciation for the complexity of a dog’s knee. It is a pretty amazing and useful joint, but unfortunately it is also one that dogs seem to injure frequently. So, if your dog does end up having some knee problems, be sure to stay in close contact with your vet. He or she can help you find the solutions that work best for your pup.

And if you are ever a contestant on a trivia show, perhaps you will get the question “Do dogs have knees?” Then you can answer with an emphatic and confident “Yes! They have two knees—one on each back leg!”

What questions do you have about dog knees?

Please comment below.

We welcome your comments and questions about senior dog care.

However, if you need medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, please contact your local veterinarian.