Is your dog pawing at his or her ears? You may be wondering if it’s normal or a sign of otitis in dogs—otherwise known as an ear infection. Integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby takes you on a trip down the “ear-ie canal” to share the signs, symptoms, and treatment options for otitis in dogs.

Did you know that otitis (inflammatory disease of the ear) is one of the most common diagnoses made in small animal veterinary medicine? This fact may not be surprising to you, especially if your dog has had an ear infection in the past. Yet, no matter how common it is, it’s no fun when it’s your dog who’s uncomfortable.

By the end of this ultimate guide, you’ll have the comprehensive information you need to speak with your vet—and help your dear dog.

- Anatomy of a dog's ear canal

- What is otitis in dogs?

- What are the symptoms of otitis in dogs?

- How do dogs get ear infections?

- 3 factors that increase the risk of otitis in dogs

- How will my vet check for otitis in my dog?

- What are the treatment options for otitis in dogs?

- Is otitis in dogs preventable?

- How should I care for my dog's ears at home?

- What if my dog has recurring ear problems?

- Navigating otitis for your dog's health and happiness

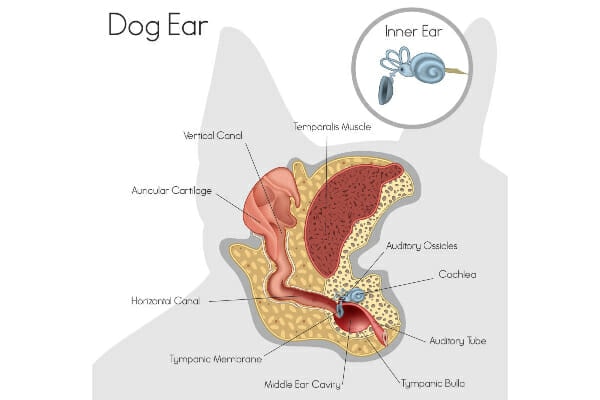

Anatomy of a dog’s ear canal

To understand otitis in dogs, first we need to take a trip down the “ear-rie canal.” Here’s a quick overview of the anatomy of your dog’s ear canal.

Your dog’s ear is composed of three segments: the external ear, middle ear, and inner ear.

The external ear

As a dog parent, you are probably most familiar with your dog’s external ear because you can see and touch it. The pinna (outer ear flap) is the part that pricks up when something catches your dog’s interest. It is also the velvety soft part that you can’t help but absentmindedly stroke while snuggling your pup.

Some dogs have upright pinnae (i.e. ears that stand up) and others have floppy pinnae (i.e. ears that hang down). And then some dogs seem to have ears that fall somewhere in the middle.

If your dog loves having his or her ears rubbed, you have probably noticed that there is a firm, tubular section at the base of the ear. This is the external ear canal. It is firm because it is made up of cartilage, which helps it keep its shape. Unlike humans who have a fairly straight ear canal, a dog’s ear canal is shaped like a “J.”

The external ear canal

This is a vertical portion, which you can see when you peer into your dog’s ear. Then the canal makes a sharp turn to become the horizontal ear canal. The horizontal canal ends at the eardrum. If you have ever watched your vet examine your dog’s ears with an otoscope, you may have noticed that he or she inserts the tip of the otoscope vertically at first. Then he or she has to turn it more horizontally to view the horizontal canal.

Your dog’s ear canal is also lined by skin. Yes, that’s right, skin. This explains why dogs who have issues with the skin on other parts of the body may also have ear problems like otitis. Skin is skin. Well, for the most part at least. The skin in the ear canals is a bit unique in that it contains glands that secrete a waxy substance known as cerumen. It is designed to trap dirt and debris in the ear canal and move it outward—a self-cleaning mechanism.

In addition to being adorable, your dog’s outer ears also serve some important functions. They act like a funnel to direct sound down your dog’s ear canal (and sometimes the pinnae look a lot like a funnel too). The outer ear also helps protect the eardrum and other sensitive structures in the ear.

The middle ear

The horizontal portion of the external ear canal ends at the tympanic membrane, commonly called the eardrum. This marks the start of the middle ear. The term eardrum is very fitting because as sound waves hit the tympanic membrane, it begins to vibrate, much like the surface of a drum does when you it hit it.

The middle ear also contains three tiny bones—the malleus, incus, and stapes. These bones touch the tympanic membrane on one side and the cochlea (a spiral-shaped, fluid-filled bony cavity) on the other side. The three bones move in time with the vibration of the ear drum. This allows them to transmit the sound wave to the cochlea of the inner ear.

All the components of the middle ear are contained within the tympanic bulla, a hollow cavity in the skull. The bulla will come into play later when we talk about ear surgery and middle ear infections. So remember this term.

The inner ear

Several structures—the cochlea, the saccule, the utricle, and the semicircular canals—make up the inner ear. As previously mentioned, the cochlea is a fluid-filled cavity. As the vibrations of the bones in the middle ear hit the cochlea, the fluid inside begins to vibrate too. This bends special hair cells in the cochlea, which turn the vibration into a nerve impulse. That nerve impulse is sent to the brain and sound is perceived.

The other components of the inner ear—the semicircular canals, saccule, and utricle—are part of the vestibular system. As such, they play a role in balance and equilibrium. The three semicircular canals are all oriented 90 degrees from one another, and each contains fluid. The saccule and utricle are also fluid-filled bony cavities.

As the dog’s head moves in space, the fluid in the these structures also moves. This bends hair cells, which turn that movement into a nerve impulse. When the nerve impulse reaches the brain, the dog can perceive the orientation and movement of the head.

Problems with these or other parts of the vestibular system can lead to old dog vestibular disease, a common affliction of senior pups which is similar to vertigo in humans.

What is otitis in dogs?

Now that we have a better understanding of the anatomy of the canine ear, let’s define otitis in dogs. The prefix “ot-” refers to the ear, and “-itis” means “inflammation of.” So, when you combine those, “otitis” technically means inflammation of the ear. Dogs with otitis often have an ear infection, so vets and dog parents frequently use the word in a practical sense to mean ear infection.

There are three main types of otitis, which are classified based on what part of the ear is affected.

- Otitis externa—inflammation (usually infection) of the external ear. This is the most common type of otitis.

- Otitis media—inflammation (usually infection) of the middle ear. Otitis media tends to happen when an external ear infection leads to rupture of the eardrum and spread of infection to the middle ear.

- Otitis interna—inflammation (usually infection) of the internal ear. Typically, this occurs when otitis media becomes severe enough to extend into the inner ear.

What are the symptoms of otitis in dogs?

Since our canine companions can’t speak to us to let us know that they are experiencing ear pain or discomfort, it’s important to observe them carefully.

Some common symptoms or clinical signs that your dog has otitis externa include:

- Head shaking

- Pawing at or rubbing the ears

- Pain around the ears

- Odor from the ears

- Abnormal ear carriage (i.e holding the ear in a funny position)

- Red ear canals

- Brown, red, yellow, or black ear debris

Dogs with otitis media may show some of the signs of otitis externa plus:

- Pain when opening the mouth

- Hearing loss

- Lack of appetite

- Head tilt

Dogs with otitis interna tend to show signs of vestibular disease, which include:

- Nystagmus (i.e. abnormal eye movements, usually from side to side but can be up and down or rotational)

- Head tilt

- Ataxia (i.e. a dog who is wobbly and off balance)

- Circling, usually in one particular direction

- Difficulty standing or walking

If your dog is experiencing any of the symptoms on these lists, it is important to get him or her to the veterinarian for an examination. Ear infections can be quite painful for dogs and could lead to hearing loss over time.

How do dogs get ear infections?

Some dogs may never have an ear infection or only a handful in his or her entire lifetime. Other dogs seem plagued by ear problems. Why? Let’s look at the three culprits behind ear diseases in dogs.

3 factors that increase the risk of otitis in dogs

Development of ear disease can be related to three factors: predisposing, primary, and perpetuating.

1. Predisposing factors

Some situations increase the risk of developing otitis.

- Genetics—This is one of the key predisposing factors. Some examples of how genetics may make a dog more likely to have otitis include the narrowed ear canals of the Shar Pei breed, the hairy ear canals of Poodles (or the increasingly popular Doodle dogs), and the long, floppy ears of Spaniels. These factors make it harder to get airflow to the ears and for debris to get out of the ear.

- Moisture— A warm, moist ear canal is a prime environment to cultivate the abnormal growth of yeast and bacteria. That is probably why vets tend to see more ear infections in dogs who spend a lot of time swimming, live in a humid climate, or have been bathed a few days ago.

- Trauma to the ear—Cleaning the ear canal improperly or using irritating agents to in the ear can cause more harm than good. This is why vets recommend using an approved dog ear cleaner and a soft cloth or cotton ball to clean the ears.

2. Primary factors

These are the conditions that initiate the inflammation within the ear canal. The most common cause of primary otitis in dogs is allergies, either to things in the environment or to food. Up to 50 percent of dogs with allergies manifest with ear involvement. Other primary causes include:

- Ear mites (much more common in cats than dogs) and other parasites

- Hypothyroidism in dogs (underactive thyroid)

- Cushing’s disease in dogs (a disease of the adrenal glands involving excess cortisol production)

- Foreign bodies (such as plant awns, which are small pieces of a plant like a foxtail)

- Other skin disorders

- Tumors

Bacteria and yeast often invade once one of these factors has set up inflammation in the ear canal. This makes the inflammation even worse. They are typically not capable of causing infection in a normal, healthy ear. Rather, the infection is secondary to whatever caused the initial problem.

3. Perpetuating factors

Sometimes there are additional factors that prevent the complete resolution of otitis in dogs. Repeated infections or longstanding infection can cause changes to the ear canals, which tends to make them thicker, stiffer, and narrower. This makes it harder for topical medications to get down into the ear canal, further reduces airflow, and impairs the self-cleaning functions of the ear. Tumors or polyps in the ear canal, while listed as primary factors, can also serve as perpetuating factors.

How will my vet check for otitis in my dog?

If you suspect your canine companion has an ear infection, it’s important to make an appointment with your vet so he or she can perform a physical examination on your dog.

At the appointment, your veterinarian will carefully check your dog over from nose to tail for any health problems. He or she will pay close attention to your dog’s skin because many dogs with ear issues also have skin issues. Additionally, the vet will look in the ear with an otoscope. This tool allows him or her to visually assess both the vertical and horizontal canals of the ears as well as the tympanic membrane.

Typically, a dog with otitis will have redness, inflammation, and debris in the ear canals. The vet is also looking for foreign material, tumors, or a ruptured or inflamed tympanic membrane. All of this information will help the vet determine the next steps for diagnosis and treatment.

Your vet may elect to do an ear cytology. This is a common and useful diagnostic test for otitis which involves swabbing the ear to obtain a sample. The ear debris is then rolled out on a slide, stained, and evaluated microscopically. This allows the vet to determine if there is yeast, bacteria, and/or other cells in the ears. He or she will choose appropriate antimicrobials based on this information.

Additional diagnostics

In chronic ear infections, some middle ear infections, or if your vet sees a bacteria on cytology that may be more complicated to treat, he or she may recommend an ear culture.

For dogs with otitis externa, your vet or vet tech will insert a sterile Culturette deep into the external ear canal to get a sample of the debris. If the vet suspects otitis media, he or she will typically obtain a sample from the middle ear during an anesthetized ear flush. Then the laboratory will identify the type of bacteria and determine which antibiotics it will or will not respond to well.

Dogs with suspected otitis media or interna may also need skull X-rays to look for abnormalities in the tympanic bulla (i.e. the bony cavity that houses the middle ear components). However, a normal bulla does not completely rule out those conditions because X-rays only show bone, not soft tissue. For this reason, advanced imaging such as MRI or CT are the best ways to evaluate the structures in and surrounding the middle and inner ear in dogs with otitis interna or media.

Why do all these diagnostics?

When your dog seems prone to get ear infections all the time, it can be easy to wonder why the vet wants to do a cytology and/or culture plus otoscopic exam each time your dog has otitis. After all, can’t you just use the same medication that worked before and skip the vet visit?

Unfortunately it isn’t that simple. Sometimes a dog will have one type of bacteria in the ear one time and a different bacteria or perhaps yeast the next time. If you whip out the old tube of ear meds you used the last time and try to treat your dog with it again, that particular medication may not be effective against the new infection.

Additionally, perhaps with the last infection the eardrum was intact and your dog just has otitis externa. However, the next time the eardrum could be ruptured and your dog could have otitis media too. As you will soon see, treatment for these two conditions is not the same. Plus, certain topical ear meds intended to treat otitis externa can get into the middle ear and damage it if the eardrum (which is the barrier between the two portions of the ear) is ruptured.

So please don’t just reach for any old tube of ear meds you have lying around if you think your dog has an ear infection. Instead, make an appointment with your vet.

What are the treatment options for otitis in dogs?

After examination of the ear and receiving any lab results, your vet may recommend any number of treatment options depending on the type of infection.

Therapy for otitis externa

The mainstay for otitis externa is topical therapy with an antibiotic, an antifungal, or combination of both medications. The exact medication will depend on whether your dog has only bacteria, only yeast, or bacteria and yeast in his or her ears.

Cytology can’t tell the vet the exact identity of the bacteria. However, knowing the shape (i.e. round circles called cocci or capsule shapes called rods) helps predict which antibiotics should be effective.

For example, most cocci are susceptible to the same antibiotics. However, rod shaped bacteria are more difficult to treat. In some cases, your vet may decide to try an antibiotic that should be effective against rods. Alternatively, your vet may recommend an ear culture to get more specific information about which antibiotic is best for that particular bacteria.

Most topical ear medications also contain an anti inflammatory—usually in the form of a steroid. This can help reduce pain and swelling in the ear, which in turn makes your dog more comfortable. Reducing the swelling also helps open up the ear canal a bit to make it easier for the medication to distribute throughout the canal.

Many ear medications are drops or ointment that you need to apply in the ear once or twice a day. After you put the medication in the ear, ensure you rub the base of the ear well to help distribute the medication. This isn’t always easy for dogs with painful ears or those who don’t like having their ears handled. The good news is that there are now a few long-lasting medications that the vet or vet nurse can put in the ear at the clinic. With those options, you don’t need to apply any ear meds at home.

Additional medications

In some cases, your vet may recommend oral medications to further combat the pain and inflammation or oral antibiotics or antifungals for severe cases. Since many dogs have underlying allergies which tend to lead to ear infections, the vet may also prescribe allergy medicine for dogs or recommend other measures to help control allergies.

Therapy for otitis media

If your dog has otitis media, the vet may elect to flush the ear well under general anesthesia and then apply an antibiotic directly into the bulla. Often, the eardrum is already ruptured in dogs with otitis media, which gives the vet easy access to the middle ear. If the eardrum is intact, the vet may perform a myringotomy. This procedure involves making a hole in the eardrum. He or she may also decide to put your dog on an oral antibiotic, antifungal, or steroid to further help reduce infection and inflammation.

Dogs with otitis media may often have otitis externa too. In that case, the vet also will typically prescribe a topical ear medication that will be effective against the otitis externa without harming the components of the middle ear. Not all medications are safe to use in dogs with a ruptured eardrum. This is one of the reasons why visualizing the eardrum during the otoscopic exam is so important.

Treatment for otitis interna

Since most dogs with otitis interna also have otitis media, the treatments described for otitis media also apply here. Additionally, since signs of vestibular disease are common in dogs with otitis interna, the vet may also recommend supportive treatment such as anti-nausea medications. He or she may also discuss how to feed a dog with vestibular disease or some tips and exercises for dogs with vestibular disease.

Surgical treatment for ear problems

Occasionally, your dog will experience an ear issue that does not resolve with medical treatment. This is where ear canal surgery may end up being a good option for your pup. Your vet may recommend surgery for:

- End stage ear canals—With chronic ear disease, the skin of the canal begins to thicken and scar. This leads to irreversible narrowing of the canal opening and eventually calcification. Sometimes this gets to the point where the ear canal feels like a huge solid rock under the skin. In end stage ears you also may not be able to find the opening of the ear canal because it is obscured by large amounts of bumpy tissue.

- Ear canal tumors—Sometimes dogs will have a tumor that grows in the ear canal. Regardless of whether the tumor is benign or malignant, the presence of the tumor can make a dog more likely to have otitis.

- Narrow ear canals—When a dog’s ear canals are unusually narrow, either due to genetics or due to chronic inflammation, it can be difficult to clean the ears and apply topical medications appropriately.

The two main ear canal surgeries are the lateral ear resection and the total ear canal ablation and bulla osteotomy (TECA-BO).

Lateral ear resection

To perform a lateral ear resection, the vet will remove the outer (i.e. lateral) portion of the vertical ear canal down to the point where it turns to form the horizontal canal. This makes the remaining ear canal a straight line, similar to the type of ear canal humans have.

For some dogs, that will allow better airflow to the ear canal and easier cleaning and treatment. However, it is important to note that the procedure is not intended to treat otitis on its own. It just makes otitis easier to manage. Depending on the location of an ear canal tumor, it can sometimes also be used to facilitate tumor removal.

Total ear canal ablation and bulla osteotomy

A TECA-BO has the potential to significantly improve quality of life for dogs with painful, constantly infected, end stage ears. It can also be useful for addressing some ear canal tumors.

This procedure involves removing the entire vertical and horizontal ear canal. At the same time, the surgeon will also open up the bulla enough to clean out all infectious debris and scrape out the epithelial lining. This addresses any middle ear infection and greatly decreases the risk of a draining tract developing from the bulla to the outside world.

Some possible complications of a TECA-BO are:

- Temporary or permanent damage to the facial nerve which runs very close to the ear canal and bulla

- Vestibular syndrome

- Post-op infections

- Development of a draining tract from the middle ear

- Cosmetic changes in ear carriage or appearance

Technically, a TECA-BO does have the potential to decrease hearing. However, most dog parents don’t report a significant change. Plus, hearing tests (brainstem auditory evoked potentials) tend to be similar before and after a dog has a TECA-BO. This is probably because dogs with end stage ears have such significant damage to the ear that hearing was already adversely affected.

Is otitis in dogs preventable?

After reading this much information about otitis, it is only natural to wonder if there are ways to prevent otitis. The answer is “maybe.” Like we discussed earlier, some dogs are naturally going to be more prone to ear infections because of genetics, underlying allergies, or other health problems.

You can’t change your dog’s genetics or cure allergies. However, there are ways to help control the effects of these factors. For example, routine ear cleaning, when done right, can be a great way to reduce the risk of ear infections. And working with your vet to keep your dog’s allergies under control can also make a big difference.

Other cases of otitis may be a bit more preventable. These tend to be the random cases that pop up shortly after a bath or swim or are related to poor ear cleaning technique. Knowing how to properly take care of your dog’s ears can go far in avoiding those instances of otitis.

How should I care for my dog’s ears at home?

Plan to clean your dog’s ears on a regular weekly schedule. Also, clean them after bathing or swimming. I recommend the following routine:

- Flush the ears with an ear cleaner solution (for example, MalAcetic by Dechra) and allow it to go down into the canals to reach the horizontal ear canal. Do not use alcohol or other substances that are not designed specifically for cleaning a dog’s ears.

- Gently massage the base of the ear for a minute or two to break up debris and wax in the canal. Then allow your dog to shake his or her head. This will bring the fluid carrying debris up from the deeper canal to the external surface.

- Next, gently wipe the fluid away with cotton balls, gauze squares, or soft fabric (like a clean, old T-shirt). You may carefully use Q-tips to wipe debris away from the visible crevices. But do not put Q-tips down into the canal as this packs down the wax and debris. Also, avoid wiping the ears with rough paper towels or other abrasive materials.

The goal of at-home ear cleaning is to make the environment less favorable for microbial growth and decrease inflammation by keeping the ears clean and dry. For more ear cleaning “do’s and don’ts” along with a step-by-step tutorial, please read my article: How to Clean a Dog’s Ears. You’ll become an ear-cleaning pro in no time!

What if my dog has recurring ear problems?

As a rule of thumb, dogs may have one “free” ear infection in their life. If otitis recurs frequently, it’s important to find the underlying cause. Long term, the only way to resolve otitis is to get to the root of the issue. I can’t emphasize this enough. The actual ear infection is only the tip of the iceberg.

Most recurrent ear problems are a manifestation of a generalized health condition. So if your dog keeps getting otitis, it is important to consult with your veterinarian. He or she can help come up with a plan to find and address the underlying problem. The end result will be a happy, healthier dog.

Chronic otitis in dogs

I am passionate about not only treating otitis but also getting to the root of the issue for several reasons. First off, otitis is probably pretty miserable for most dogs. Imagine having an intensely itchy and painful ear. It wouldn’t be fun at all.

Second, chronic ear infections can lead to the changes in the ear canal that we discussed earlier. The more infections a dog gets, the more the ear canal becomes narrowed and thickened, and the more ear infections the dog may get. This cycle will potentially continue to repeat for the rest of your dog’s life. Sometimes that may lead to deafness or end stage ears. And if nothing else, it leads to less comfortable days for your pup.

I do want you to know, though, that sometimes you can do everything right and still end up with a dog who has chronic otitis. So don’t feel guilty if your dog needs a TECA-BO, goes deaf, or seems to have one infection after another. I have met some very dedicated dog parents over the years who did every single thing I ever suggested. Yet their dogs still had major ear issues. So do what is in your power to help your dog, but don’t obsess over what you can’t control.

Navigating otitis for your dog’s health and happiness

At the end of the day, otitis in dogs is common. But that does not mean your dog has to suffer silently. There are solutions. By being an observant pet parent and speaking with your veterinarian if you suspect your canine companion has an ear infection, you’re well on your way to giving your dog the happiest, healthiest life possible. You, your dog, and your vet can make a great team!

What questions do you have about otitis in dogs?

Please comment below.

Hi I just read your article after searching on the internet for puppies born without an ear canal. My 4 month old cockapoo had an experience the other night where he walked like he was drunk. He has been completely fine since but when inspecting his ears I have noticed he has no ear canal in his right ear. We have noticed since we brought him home at 8 weeks of age that he has trouble picking up where sounds are coming from. He has shown no signs whatsoever of an ear infection. Can a dog be born this way and live like this?

Hi Randy,

Yes, it is possible for a dog to be born with just about any congenital abnormality you could imagine. I don’t see any reason why the lack of an ear canal would be life threatening. With that being said, I highly recommend you have your pup evaluated by a veterinarian. Sometimes when one birth defect is present, there can actually be others present that are hidden or just not as noticeable. It would be a good idea to let your vet do some investigation and make sure no other issues are found that would be of concern. I am hopeful your little guy will lead a long and full life. Best wishes!

Very interesting and comprehensive article.

I recently adopted a lab who came from a hoarding situation. We thought he was deaf but it turned out he had a severe ear infection in both ears. Fortunately after a couple of months of treatment from an excellent vet, he is able to hear.

Hi Sandra,

Thank you for the kind words about the article. I am glad to hear that your rescue dog is well and happy. It sounds like you have a good relationship with your veterinarian which I hope will serve you well for years to come. Best of luck to you and yours!

I found your website looking for ways to help my getting older dog and saw this blog post about Otitis. I checked around for the product you recommend, Oticalm, but it is seems to be no longer available. Would you recommend another product and I’d encourage you to update your blog post to keep it current.

Thanks for your obvious care and love for dogs and your very informative website.

Dear Eric,

Thank you for catching this; I do need to update this blog! But in the meantime, the ear cleanser that I prefer is called MalAcetic by Dechra. However, I always recommend following your veterinarian’s instructions for the treatment and medicating of your dog. Thanks!