Discover how one pony played a hero’s role in helping pioneer animal orthotics for all pets. Integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby recalls this true and poignant veterinary story along with helpful tips about canine orthotics and prosthetics.

Pioneering animal orthotics: A veterinarian’s story

The memory of a pony named Penny had been buried in my heart for so long that I might have lost it, had it not been for a commercial I saw recently.

The heartwarming commercial was for Orthopets, a company that fabricates custom dog braces, prosthetics, and orthotic devices for pets. It was then that I remembered Penny.

Penny (and the notion of animal orthotics) was born

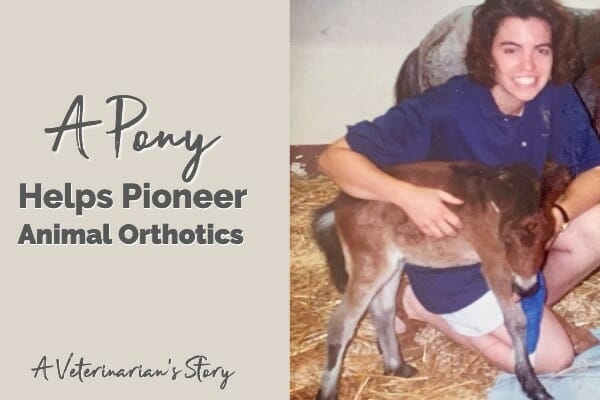

Twenty-five years ago, Penny (a newborn foal), Terry (an angel volunteer), and I (a vet student at the time) pioneered the notion of veterinary orthotics at the University of California Davis. I say this tongue in cheek, but Penny was indeed a pioneer, in more ways than one.

Penny was a horse, more specifically, a pony. She was the first of her breed to ever be born on U.S. soil. Her mother had been imported by a California family, and both the mare and Penny were deeply loved as family pets and valuable investments.

I was between my second and third year of veterinary school at the time, which made me, medically speaking, pretty much worthless. I had finished all my dissecting labs and microscope courses, but I had no hands-on knowledge and had never worked on actual patients.

Miraculously, I was accepted to UC Davis as a summer extern, working along senior students in their clinical rotations. This news made me as happy as I had been the day I had received my veterinary school acceptance letter.

Rounds and new responsibilities at UC Davis

Since my roommate for the summer was from the West Coast, she offered to pick me up from the airport. In her huge white Lincoln Continental that her aunt had given her, we drove down to Sacramento where we’d subleased a meager apartment.

I showed up for the first day of my veterinary externship with a stethoscope, a notebook which I had divided into 26 alphabetical sections, and a willing attitude. Like the senior students, I had my own “cases.” However, a veterinary resident oversaw each patient and case. They were the real veterinarians. My responsibilities included checking and recording my patients’ vital signs twice a day, administering prescribed medications, and reporting any concerns to the doctors, who were actively overseeing all affairs.

Daily life as a summer veterinary student extern

Every morning our team met for rounds at 8 a.m. Prior to that time, we completed each patient’s treatments. This meant that I arrived at the veterinary hospital around 6:30 a.m. each morning.

Rounds were my favorite part of my summer externship. The head of the department was a god in the field of equine medicine and a gifted teacher. To this day, I consider him the standard by which every veterinarian should be measured.

After rounds, the vet students and residents would sit around a small conference table and update the head of the department on our cases. He’d lead discussions about diagnoses and current research, and treatment plans would be updated accordingly. Every morning, I frantically scrawled in my notebook as we went over cases.

A pony foal presents at the vet teaching hospital

Midway through the summer, Penny presented to the veterinary teaching hospital at UC Davis. The foal was admitted because she had been born unable to use her legs. Specifically, her two front legs wouldn’t support her weight.

I don’t remember an actual diagnosis, but there was a problem with her tendons and ligaments. Penny simply didn’t have the structural support to stand. Typically, a normal foal stands and starts nursing within an hour of birth, so this was a critical situation for Penny.

I was delighted to be assigned the case of this pony foal. Not only because I appreciated the medical intricacies of her condition, but also because I just wanted to hug her!

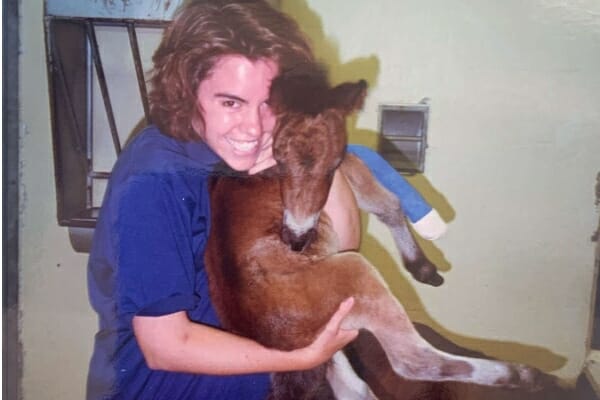

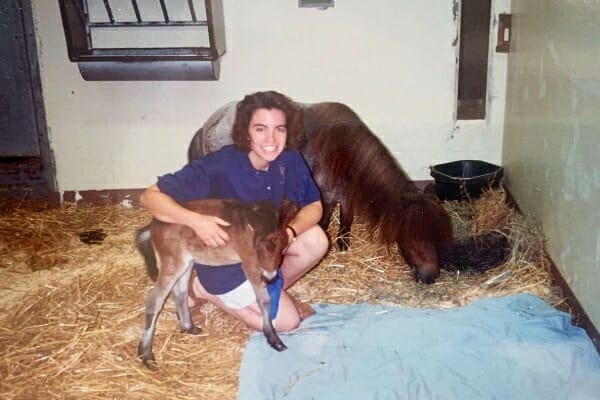

Penny weighed about 45 pounds and looked like a stuffed animal. I spent all my spare time in the stall with Penny and her mom, stroking them and willing Penny to be well.

I don’t remember what the official plan was for Penny, but she had been there a few days and wasn’t improving. Then the idea struck me. What Penny needed was leg braces! If her column of bone could be supported, maybe she could stand and walk on her own, and her soft tissue could develop normally. And if she could do that, maybe her legs would grow straight and strong and she would survive.

Connecting the dots…

I hustled over to the desk in the barn and began rummaging through the drawers for a phone book. At the time, I didn’t even know what the people who made custom crutches and braces for humans were called. Eventually, I found an appropriate local number in the yellow pages and called it.

I can only imagine what I might have said, but I’m sure I said it with pleading desperation. The receptionist put me through to Terry who was the co-owner of the company. Miraculously, Terry agreed to see Penny the next day and take a look at her legs.

Because it was such a long shot, I hadn’t consulted my veterinary superiors before making the phone call. Now I had to scramble to get permission from those in authority. They were perhaps skeptical, but still very supportive.

The physical examination

The next day a dark-haired man arrived in khaki pants and polo shirt, carrying his bag of tricks. I remember Terry being so genuinely kind that I didn’t even think to ask his motivation for helping us. Terry was very at ease greeting Penny and the mare, and he confidently began his examination.

He moved Penny’s joints through ranges of motion, took tools out of his bag and made measurements, and eventually made molds of the foal’s legs. Vet students filtered in and out of Penny’s barn while Terry did his work. Penny would have her braces within a few days.

It was during those interim days that the head of the department approached me and asked what financial arrangement I’d made with Terry’s company. In my business-naive mind, I had simply assumed any company would be thrilled to donate their time and services to help Penny.

A slow panic overcame me as I stammered to explain my logic. I assured him that I would call Terry and iron this out. In my mind, I practiced how that conversation was going to go. I couldn’t come right out and say, “Hey, I assumed you were doing this for free. I hope you feel the same!”

Making that phone call filled me with dread. Fortunately, relief quickly took its place. Terry assured me that he was doing his work gratis. And, even though I never knew my clinicians to be anything but self-assured and in control, I think they looked visibly relieved when I shared this good news with them.

Bracing for the future: Penny’s first steps

Terry returned for the fitting several days later. After he strapped on the braces, which held Penny’s front legs in extension, I carried her out to the grassy area in front of the barn. Another student led Penny’s gentle mother. A crowd had gathered for the unveiling of Penny’s “new legs.” I stood Penny up and stabilized her for a minute, afraid to let go.

After getting her balance, Penny took her first tottering steps. She was so small and fuzzy. She looked more like something you’d find on the shelf at FAO Schwartz than in a horse barn. But for the first time in her young life, Penny was—under her own power—moving as a horse should.

Things changed in a heartbeat

At some point, the department head moved in for a closer look and, kneeling down, gathered her to his chest. Instinctively, he began to examine her (for the first time). Had it been a movie scene, the orchestra’s robust song of triumph would have come to a screeching halt. He listened to her heart and found a heart murmur—a significant heart murmur.

I was the student on the case. Although I had listened to Penny’s heart many times, I never detected the murmur. I had been focused on the face of my watch, counting how many beats occurred in 15 seconds and multiplying by four. (That was my level of expertise.) The accountability fell on the resident veterinarian who was in charge of Penny. However, to this day, I feel bad about not detecting Penny’s heart murmur. (If you’ve ever felt guilt or pain from the past, please read my article: 3 Life Lessons for Dog Moms.)

Within hours, a team from the radiology department showed up at Penny’s stall with their $250,000 mobile ultrasound unit. A board-certified cardiologist examined the foal’s heart as she lay cooperatively on a padded gurney. The conclusion was not good. Penny had a severe congenital heart defect.

Blindsided

I was still naively celebrating the victory of her mobility. I never expected the news that would follow.

The owners were contacted and the decision to euthanize was made. I remember the resident telling me that I didn’t have to be the one to do it, but I was the frontier boy in Old Yeller. I knew I had to be the one.

Soon after, someone handed me a syringe of thick pink syrup. Penny had an IV catheter in place, so there was no technical expertise required. I don’t remember anyone else in the stall with us. It was quiet and my focus was completely on Penny.

I took some time to say my peace, and then inserted the needle in the IV port to inject the solution. I could accomplish that while blinded by tears.

A gift from Penny’s family

On my last day at the vet school that summer, the department head handed me a wrapped present. It was a veterinary handbook that he had authored on equine neonatal medicine. He had thoughtfully inscribed it, which was a gift in and of itself, but he told me the book had been purchased for me by Penny’s family.

I returned to Kansas State University, completed my final two years of veterinary school, and have now practiced veterinary medicine for over two decades. As I grew my family, I transitioned from predominantly equine medicine to exclusively small animal medicine.

Sometimes a new client will pay me a tremendous compliment by saying, “That is the most thorough exam my dog has ever had.”

The truth is, I couldn’t practice veterinary medicine any other way. A little pony, who lived but a few days, taught me that life lesson.

Animal orthotics today

While Penny’s story still brings tears to my eyes 25 years later, I find solace in knowing that her spirit lives on through the role she played in pioneering the field of veterinary orthotics and prosthetics.

Today, animals of all kinds receive orthotic and prosthetic devices that dramatically improve their quality of life. At one time or another, some of the senior dogs under my veterinary care have worn devices for medical conditions including canine elbow dysplasia and degenerative myelopathy. In fact, ToeGrips® dog nail grips (my company’s flagship product) are an assistive device that fit on a dog’s toenails to restore mobility on hardwood floors and smooth surfaces.

5 more quick facts about animal orthotics and prosthetics for dogs

- Prosthetics refers to devices that “replace” a missing limb. Orthotics refers to devices that “enhance” the use of a limb or body part. (Knee braces are one example of an orthotic device.)

- Cranial cruciate ligament tear, achilles tendon rupture, and carpal hyperextension are a few of the common canine conditions where orthotics or prosthetics may help.

- The benefits of orthotic and prosthetic devices for dogs range from restoring a dog’s active lifestyle to preventing the decision to euthanize.

- Your veterinarian can help you determine whether your dog is a candidate for orthotic or prosthetic devices.

- For more information about animal orthotics for dogs, please read my articles: Can Orthotics and Prosthetics Help My Pet? and How Veterinary Rehabilitation Medicine Uses ToeGrips® Dog Nail Grips.

Afterword…

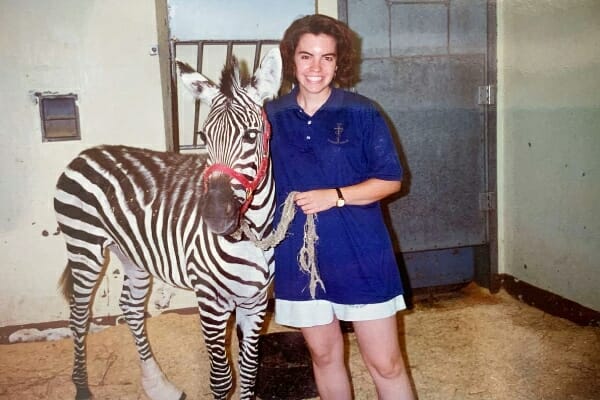

Terry McDonald, the kind volunteer who fitted Penny with braces, practices at Anchor Orthotics and Prosthetics today. He’s been an angel to both people and pets for over 28 years, continuing to provide care for humans and animals—cats, dogs, alpacas, and of course, horses. Additionally, he has developed custom braces for the UC Davis Veterinary School of Medicine.

Dr. Julie Buzby, the vet student who didn’t give up, practices today in South Carolina and founded Dr. Buzby’s Innovations—a small, family-owned business focusing on senior dog care and mobility. She still loves all creatures great and small.

We welcome your comments and questions about senior dog care.

However, if you need medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, please contact your local veterinarian.