DCM in dogs (i.e. dilated cardiomyopathy) is a condition where the heart muscle becomes weak and has trouble pumping blood through the body. Discover the causes, symptoms, stages, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis from integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby.

Your dog’s heart beats 60 to 150 times every minute, depending on their body size. Each contraction pumps oxygen-rich blood throughout the body and moves blood to the lungs to get “refilled” with oxygen.

So as you can imagine, if the heart can’t pump blood as effectively, as occurs in canine dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), this could be a significant problem.

What is DCM in dogs?

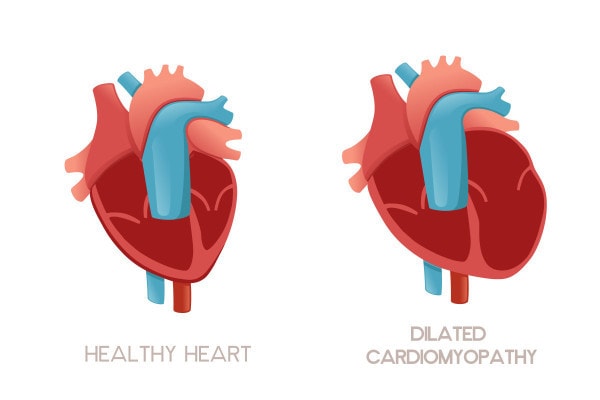

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in dogs is a heart disease characterized by two major changes to the heart—decreased ability to pump blood and enlargement of chambers, especially the left ventricle (i.e. bottom left chamber of the heart that sends oxygenated blood out to the body). It is the second most common heart disease in dogs.

The first thing that happens in DCM is that the heart muscle itself in becomes weaker. Thus, it can’t contract as strongly to send blood out of the heart and to the rest of the body. As a result, less blood leaves the heart with each heart beat. The increased volume of blood being “left behind” leads to dilation (i.e. enlargement) of the chambers of the heart, especially the left ventricle. And the walls of the heart become thinner and stretched out.

As these changes continue to progress, the heart becomes a less and less effective pump. And eventually the dog may go into congestive heart failure as a result of DCM.

Over time, the changes to the shape and size of the left ventricle can also affect the function of the mitral valve. This valve sits between the left atrium (i.e. upper chamber) and left ventricle (i.e. lower chamber). And its job is to ensure that blood only moves one-way (i.e. from atrium to ventricle). But when the left ventricle stretches and changes shape, this may alter the way the valve closes, leading to the valve leaking. This causes a heart murmur in dogs.

Additionally, the changes to the heart that occur in dilated cardiomyopathy can predispose a dog to abnormal heart rhythms. Unfortunately, some of these arrhythmias can be fatal.

What causes DCM in dogs?

There are two kinds of DCM in dogs—primary DCM and secondary DCM.

Primary DCM

Dogs with primary DCM usually have the genetic form. It is hereditary in certain breeds, yet not all at-risk dogs will develop active DCM. Dilated cardiomyopathy is a disease that predominantly affects large and giant breed dogs.

Dog breeds prone to DCM include:

- Irish Wolfhounds

- Great Danes

- Doberman Pinschers

- Newfoundlands

- Boxers

- Standard and Giant Schnauzers

- Cocker Spaniels

- Welsh Springer Spaniels

- Golden Retrievers

- Portuguese Water Dogs

However, primary DCM can also be idiopathic, meaning there is no identifiable cause. Or in some cases, it can be inflammatory (i.e. the immune system targets special cell receptors in the heart).

The average age at diagnosis is six years for most dogs with DCM. However, primary DCM can occur in dogs as early as puppyhood. One study found Portuguese Water dogs can show signs of primary DCM anywhere from one to six weeks of age. When the vet diagnoses the dog with DCM at such a young age, the disease progresses much more rapidly. And affected dogs typically die before 12 weeks of age.

Secondary DCM

Secondary DCM occurs as a result of damage to the heart from some other cause. While primary DCM tends to occur in purebred dogs and is rare in mixed breed dogs, any dog can be at risk for secondary DCM.

Some of the underlying causes of secondary DCM include:

- Infections (e.g. parvovirus and Lyme disease)

- Toxin exposure or certain medications (e.g. doxorubicin)

- Metabolic conditions (e.g. hypothyroidism in dogs, Addison’s disease in dogs)

- Taurine deficiencies (Golden Retrievers and Cocker Spaniels, or mixes of either breed, may have trouble metabolizing the amino acid taurine, which helps with heart function).

- Nutritional disorders and eating a grain-free, legume-rich diet

Nutritional DCM

The last item on the list above, nutritional DCM, bears discussing a bit more. Over the past several years, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been investigating a link between grain-free, legume-rich diets and DCM in dogs. There was an increase in DCM cases reported among dogs of breeds who typically didn’t get primary DCM. And grain-free diets seemed to be the common denominator. Additionally, veterinarians noticed that discontinuing the grain-free diet helped reverse the changes associated with DCM in some dogs.

This lead them to propose that there was a nutritional link to the DCM. Experts originally thought that taurine deficiency was the primary problem, but some affected dogs had normal taurine levels. Thus, the investigation continues. It is possible there are multiple contributing factors to diet-associated DCM.

What we do know, though, is that the cases seemed to be associated with feeding non-traditional diets (both grain-free and grain-inclusive) that contain high amounts of peas, lentils, chickpeas, dry beans, white potatoes, or sweet potatoes. Until we have more information about how these diets can increase the risk of dilated cardiomyopathy, veterinary cardiologists recommend avoiding these foods. The best food to feed your dog is the one your veterinarian recommends.

What are the symptoms of DCM in dogs?

As DCM progresses and the heart becomes a less efficient pump, this will take a toll on the body. Some of the symptoms of DCM are related to the heart’s inability to supply the necessary amount of oxygenated blood to the body. And other symptoms of dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs occur because blood can back up into the lungs (or occasionally the body) while waiting to get through the heart. This leads to congestive heart failure.

Early symptoms of DCM in dogs

In the early stages of DCM, dogs may not show any clinical signs at all. Sometimes, unfortunately, the first indication that a dog had DCM is sudden death from a fatal arrhythmia. This is especially common in Doberman Pinschers and Irish Wolfhounds.

Symptoms of advancing DCM

As heart function continues to decline and the dog develops congestive heart failure, you may notice the following symptoms:

- Exercise intolerance—A dog who can normally play fetch or go for long walks may suddenly slow down or need to make more stops.

- Weakness or collapse—Your dog may look weak and wobbly or suddenly fall over.

- Being a lethargic dog—Decreased oxygen delivery to the tissues can lead to your dog being tired or sluggish.

- Lack of appetite—Dogs with heart disease in dogs may not feel like eating, especially if they are struggling to breathe.

- Increased respiratory rate—Your dog may be breathing fast, especially if fluid is building up in the lungs due to heart failure. Sometimes an increased resting or sleeping respiratory rate (above 30-35 breaths/minute) can be the first indication of worsening heart disease.

- Difficulty breathing—Your dog might be breathing hard, gasping, or looking like it takes more effort to breathe than normal.

- Blue or purple gums—When your dog isn’t getting enough oxygen, his or her gums will be blue or purple rather than a nice pink color.

- Coughing—Fluid in the lungs can also trigger a dog to start coughing and gagging, especially at night.

- Difficulty sleeping or getting comfortable—Your dog may be restless because it is hard to breathe, especially when lying down.

Seek veterinary care immediately if you see these symptoms

The best thing you can do is get your dog to your vet or make an emergency vet visit immediately should you see these symptoms. If you are wondering when to take your dog to the emergency vet, a good rule of thumb would be to consider emergency care anytime your dog is having trouble breathing, has collapsed, or you otherwise feel his or her condition is serious.

How will your vet diagnose DCM?

As part of the vet visit, your vet will perform a thorough physical exam, paying special attention to your dog’s:

- Heart rate, sounds, and rhythm—Dogs with DCM may have a heart murmur, or a “gallop” rhythm or other irregular heart rhythms. And they may have an elevated heart rate.

- Lung sounds and respiratory rate—Abnormal lung sounds such as crackles can indicate fluid in the lungs (a possible symptom of CHF). And dogs with CHF may also have an elevated respiratory rate.

- Femoral pulses—If your dog’s pulses are weak, this may also point to heart disease.

Additionally, depending on the severity of the dog’s symptoms and the results of the physical exam, the vet may suggest a variety of other diagnostic tests. Your family veterinarian can perform some of these tests. But others require referral to a veterinary specialist near you, namely a veterinary cardiologist.

Taurine levels

If your dog is on a grain-free, legume-rich diet or is a breed that is prone to taurine deficiency, the vet may recommend testing blood taurine levels.

NT-proBNP

Another blood test for dogs called an NT-proBNP can help determine if there is a problem with the heart. When there is any stretching of the heart walls or an enlarged heart, levels of NT-proBNP (a special type of heart-related protein) in your dog’s blood will increase.

ECG or Holter monitor

The vet may want to perform an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) to assess your dog’s heart rhythm. The ECG allows him or her to detect arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation or ventricular premature complexes (VPCs). Additionally, a Holter monitor, which records a continuous ECG over a day or more, can be helpful. It may pick up arrhythmias that a shorter ECG could miss. And it gives the vet an idea of how often the irregular heart rhythm is occurring.

Chest X-rays

Chest X-rays (i.e. radiographs) allow the vet to get an idea of the size and shape of the heart. Plus, they are a great way to pick up signs of congestive heart failure such as pulmonary edema.

Echocardiogram

An ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) is the best way to diagnose DCM. It allows the veterinary cardiologist to evaluate the size and function of each heart chamber, the thickness of the walls of the heart, and the flow of blood through the valves and great vessels.

Genetic testing

There is a genetic test for the mutations linked to DCM available for Portuguese Water Dogs, Doberman Pinschers, Standard and Giant Schnauzers, Welsh Springer Spaniels, and Boxers.

Screening for DCM in at-risk breeds

Since we know there is a genetic link, it is possible (and recommended) to screen at-risk breeds. This can help catch early DCM before the dog becomes symptomatic. Starting at the age of three to four years, veterinary cardiologists recommend all at-risk breeds should have yearly Holter monitor readings and echocardiograms. If this is not possible, NT-proBNP testing coupled with X-rays and an ECG can be helpful.

What are the stages of DCM in dogs?

Based on the information the vet gathers, he or she can classify your dog’s DCM into a particular stage. There are four stages of dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs. The stages are based on the human staging system for DCM, and they are similar to the stages used to characterize mitral valve disease in dogs.

- Stage A—These dogs are not affected by DCM but are at risk for it due to the presence of the gene that causes DCM or due to being one of the at-risk dog breeds.

- Stage B—There are structural and/or electrical changes present in a dog’s heart, but there is no congestive heart failure (CHF).

- Stage C—Same as stage B but now there is evidence of CHF.

- Stage D—End-stage DCM in dogs. The CHF that is present is no longer responsive to standard treatments.

What is the treatment for DCM in dogs?

Once the veterinarian diagnoses your dog with DCM and determines the stage, he or she will discuss the treatment plan with you.

Nutritional DCM

In cases of nutritional dilated cardiomyopathy, switching away from a grain-free diet or grain-inclusive non-traditional diet can partially or completely reverse the changes associated with DCM. However, some dogs, especially those with evidence of CHF, will require heart medications too.

Early DCM

In early dilated cardiomyopathy (i.e. evidence of DCM on echo but no clinical signs of DCM yet), your veterinarian may prescribe a medication called pimobendan (Vetmedin®). This recommendation is based on the PROTECT Study. It showed that pimobendan extended the time to onset of CHF and increased survival times in Dobermans with subclinical DCM. Pimobendan helps improve the strength of the heart pumping and dilates blood vessels. This makes it easier for blood to travel to the rest of the body.

Additionally, the medication benazepril may also help slow the disease process in early DCM.

Clinical DCM

Dogs who are showing symptoms of DCM can also benefit from pimobendan. Plus, the vet may prescribe diuretics (e.g. furosemide or spironolactone), especially if there is fluid in the lungs. And he or she may also decide to put your dog on an ACE-inhibitor such as enalapril for dogs or benazepril. Additionally, some dogs may also take anti-arrhythmia medications like amiodarone or mexiletine.

End-stage DCM

Dogs with end-stage DCM or severe congestive heart failure may require hospitalization and oxygen support. Sometimes it is possible to get them stabilized enough to go home on oral medications. But in other situations, you may need to make the difficult decision to euthanize your dog with heart failure. DCM in dogs isn’t painful per se. But struggling to breathe is very distressing for a dog, and congestive heart failure is akin to drowning. This means sometimes the kindest thing may be to set your dog free.

Natural ways to support heart health

There are some potentially useful supplements for dogs with DCM. Supplemental taurine is helpful for dogs who have a suspected or diagnosed taurine deficiency. And dogs such as Dobermans or Cockers may benefit from a carnitine supplement.

Coenzyme Q10 supplementation has been shown to help with human cardiovascular health, though data is lacking in veterinary medicine. Omega-3 fatty acids for dogs, however, are proven to have anti-inflammatory effects and promote heart health in dogs.

What is the life expectancy for dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy?

The prognosis for dogs with DCM can vary depending on the age of the dog, the type of DCM, the severity at time of diagnosis, and other factors.

In general, dogs who receive a DCM diagnosis at a younger age tend to have a poorer prognosis. Additionally, poor prognosis is linked to:

- Certain changes on ECG (prolonged QRS complex)

- Poor ability to pump blood out of the heart (i.e. decreased ejection fraction) and restricted flow through the mitral valve on echocardiogram

- The presence of ascites (i.e. abdominal fluid build up, causing a pot-belled dog appearance)

- The class of congestive heart failure

- Higher total bilirubin levels on blood work

Additionally, Dobermans may be more prone to sudden cardiac death if they have a severely dilated left ventricle (i.e. severe volume overload) or atrial fibrillation. And noting spontaneous VPCs (ventricular premature complexes) on an ECG is linked to sudden death in Irish Wolfhounds.

Overall, the prognosis for dogs with nutritional dilated cardiomyopathy is better than for dogs with primary DCM, assuming the dog survives the first few weeks after diagnosis. It is possible for the heart to return to normal (or closer to normal) with diet change, but this can take months.

Sadly, dogs who have DCM and CHF generally only survive about 3 to 12 months. And three out of four Dobermans with CHF will succumb to their disease within three months of receiving the diagnosis.

How can you prevent DCM in dogs?

Unfortunately, primary (breed-related) DCM isn’t entirely preventable. However, using good breeding practices such as screening prospective parents of at-risk breeds for DCM before breeding can help decrease the chances of DCM. And having your at-risk breed screened for dilated cardiomyopathy regularly can help you catch it early.

On the other hand, secondary DCM is somewhat more preventable. To decrease the chances of your dog developing DCM, avoid feeding non-traditional diets with high amounts of legumes or potatoes unless specifically directed to do so by your vet. And ensure your dog receives all necessary and risk-based vaccinations and is on an effective tick preventive.

Work with your vet

If your dog has been diagnosed with DCM or you have a breed that is at a higher risk for DCM, the best thing you can do is to work closely with your vet and follow his or her instructions. For a dog with DCM, this may mean giving all medications as directed, making a diet change (if needed), and keeping all follow-up appointments. Or for an at-risk breed, this may involve consulting with a veterinary cardiologist and starting a DCM screening program if indicated.

In the midst of the appointments, medications, and worry, it is also important to remember to take time to enjoy your dog. Unfortunately, especially when it comes to primary DCM, tomorrow isn’t guaranteed. But you have today. So why not carve out some time to spend with your dog. Being with your dog is good for your heart, and for your dog’s heart too.

Has your dog been diagnosed with DCM?

Please share his or her story below.

My Buster was diagnosed with DCM 10/16/2024 and he succumbed to the devastating effects of this disease on 2/2/25. His would have been only 4 years old on 3/29/25. I rescued him when he was 15 months old. He was a good boy, big boy, 96 lb Boxer. I’m so broken hearted 💔. Had I known about DCM I would have rescued him anyway. 2 1/2 years of he being in my life left a huge hole. I loved him 😢 I wished I had answers as to why and what causes this disease. If it’s irresponsible breeding then that needs to stop! I would love to know.

Dear Janie,

I am so sorry for the loss of your beloved boy. While I know you would have done anything to give him more time, I am certain he knew how much he was loved and that the two years he spent by your side were full of joy. You are correct that DCM is genetic in Boxers and their breed carries a high risk for heart disease (and cancer). I hope with time the grief will begin to fade, and your heart can find peace. May Buster’s memory stay with you always and continue to be a blessing in your life.

Dear Dr. Buzby, I cannot tell you how much I appreciated you responding about my loss of Buster. Through the tears, I do know that he knew I loved him and I rescued him for such a time as this. I pray a special blessing over you and what you do for all our fur babies and for the pet parents who love them so.

God bless 🙏❤

With a grateful heart~

Janie Munroe