If you’ve found a new lump or bump on your dog, cyst vs. tumor may be the next question in your mind. How will you know the difference? And what might it mean for your dog? To help put your mind at ease, integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby breaks down how to differentiate a dog cyst vs. tumor and outlines some of the more common types of skin lumps in dogs.

You find an unfamiliar bump on your dog’s skin. Your mind races. How long has it been there? Is it painful? Is it benign or malignant (cancerous)? Is it a harmless cyst or a potentially dangerous tumor? How worrisome is this?

All of these are valid questions, and ones your veterinarian can help answer.

Dog cyst vs. tumor

While I wouldn’t describe any new growth as “normal,” some certainly are more worrisome than others. Cysts are most often benign, whereas a cancerous tumor may potentially be life-threatening. So what’s the difference?

Cysts are hollow pockets of tissue that are filled with liquid or other material. And tumors, whether benign or malignant, are comprised of solid tissue that forms from abnormal cell growth. Both types of lumps can occur anywhere on the body and can vary in size.

Let’s take a look at both in more detail, starting with cysts.

What are cysts in dogs?

Cysts in dogs (i.e. masses made up of a cavity that contains liquid or semi-solid material) can be very small, or they can grow quite large. They typically appear on, in, or under the skin of the head, neck, trunk, and eyelids, or in between the toes. Cysts are not contagious between dogs, and they do not spread to other parts of the body the way cancer might.

What are the types of cysts in dogs?

There are five main categories of cysts in dogs:

1. True cysts

True cysts form in glands and have a lining that secretes fluid. The more fluid the cyst lining secretes, the larger the bump. Often, true cysts are associated with sweat glands and tend to occur around the eyes or in the ears of the dog. They form a lump that is translucent and dark or bluish and may leak yellowish material.

2. Follicular cysts

Follicular cysts, also called epidermoid cysts, form in hair follicles and are common in dogs, especially Boxers, Shih Tzus, Schnauzers, and Basset Hounds. This type of cyst can contain fluid or a more solid caseous (i.e. cheesy) material. Follicular cysts are prone to inflammation and may become infected.

One common type of follicular cyst is an interdigital cyst in dogs. These cysts develop between the toes and are often a consequence of allergies, obesity, or breed-related factors. As part of the disease process, the affected hair follicle becomes inflamed and may rupture. The resulting itchiness makes the dog prone to licking the paws, which in turn perpetuates the infection and inflammation.

3. Sebaceous cysts

Another common type of cyst, sebaceous cysts in dogs, are associated with the sebaceous glands (i.e. oil glands) near hair follicles. These cysts are usually filled with a greasy substance called sebum, and may have a bluish or white appearance. Sebaceous cysts form when excess sebum builds up, potentially due to blockage of the gland opening. Like follicular cysts, sebaceous cysts are prone to infection. Plus, they may break open or bleed.

4. Dermoid cysts

Dermoid cysts are congenital (i.e. occur during development). However, they may not become obvious until the dog is 9 to 12 months of age. Unlike other types of cysts, dermoid cysts are rare in dogs. But when they do occur, they are more common in Rhodesian Ridgebacks and Kerry Blue Terriers.

5. False cysts

False cysts differ from true cysts because they lack a secretory lining. Instead, they develop secondary to bleeding and trauma to the area. False cysts are common in dogs, and they typically contain dead liquefied cells that resulted from the initial injury. Generally, false cysts tend to have a dark appearance.

What is the treatment for cysts in dogs?

The treatment for cysts varies based on the type, size, and location of the cyst. If the cyst is small and not causing any problems for the dog, it may not require treatment at all. Often, the vet will recommend simply monitoring a cyst. Or if it becomes infected, your vet may prescribe a course of antibiotics.

However, in some cases the cyst is problematic for the dog. It may be in an uncomfortable location, such as happens with some cystic dog eyelid masses. Or it may have ruptured or grown very large. In those cases, the vet might recommend having the cyst surgically removed.

What are tumors in dogs?

On the other hand, tumors are solid masses made up of cells that started dividing abnormally. They can be benign or malignant. While it would be impossible to cover every type of cancer or every benign tumor that occurs in dogs, we can highlight some of the tumors that are commonly mistaken for cysts.

Types of tumors that could look like cysts

Some common tumors that may resemble cysts include:

Mast cell tumors

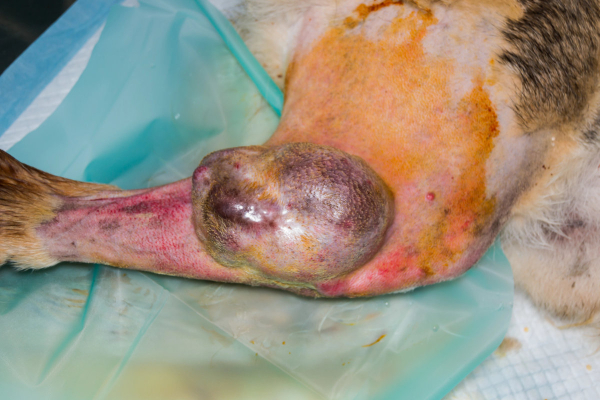

Mast cell tumors in dogs (MCTs) are the most common type of skin cancer in dogs. They can occur anywhere on the body, and may be on the skin (i.e. cutaneous) or just below the skin (i.e. subcutaneous).

The challenging thing about mast cell tumors is that they can have variable presentations. MCTs can be soft, firm, big, small, raised, hairless, ulcerated, discolored, etc. There is really no way to diagnose an MCT just by looking at it. And they may look like cysts or benign tumors.

It is important to know that mast cells, which are part of the immune system, are filled with histamine granules. Therefore, squeezing or otherwise aggravating a mast cell tumor may cause the mast cells within to degranulate, releasing large amounts of histamine. This can cause anaphylaxis (i.e. a serious allergic reaction).

Histiocytomas

Cutaneous histiocytomas are pink, round, raised, and sometimes ulcerated lumps primarily seen in young dogs. They can look a lot like mast cells tumors, so it is common for people to wonder if they are dealing with a mast cell tumor vs. histiocytoma in dogs.

However, unlike mast cell tumors, histiocytomas are benign tumors that generally do not require treatment or removal. Instead, the dog’s own immune system eliminates the mass. Once they spontaneously regress, histiocytomas usually do not recur.

Melanomas

Dogs can get melanoma just like people. These masses can occur on a dog’s skin—usually on the trunk or near nail beds. Or melanoma can cause dog mouth cancer. Typically, melanoma on the skin is benign, whereas nail bed and oral masses are more likely to be malignant melanoma.

Melanoma in dogs may be darkly pigmented or pink in color (amelanotic melanoma). One very exciting fact is that veterinary oncologists have created a melanoma vaccine for dogs that is useful for treatment (but not prevention) of oral melanoma.

Squamous cell carcinomas

Squamous cell carcinoma is a rare form of skin cancer in dogs. It is most common in light-skinned, short-haired dogs, especially those with a lot of sun exposure. These masses can be raised, firm, and ulcerated. Additionally, dogs may develop squamous cell carcinoma in their mouth.

Blood vessel tumors

Small, dark red to black, circular masses on a dog’s skin may be tumors of the blood vessels. These can either be benign (i.e. hemangioma in dogs) or malignant (i.e. hemangiopericytoma). Because these tumors have variable appearances and can be hard to distinguish from each other, generally the vet will make the diagnosis based on biopsy results.

Adenomas or adenocarcinomas

Not all growths from sweat glands or sebaceous glands are cysts—tumors are possible too. Benign glandular masses are called adenomas, and malignant masses are called adenocarcinomas. Generally, these masses are small (although adenocarcinomas may grow larger as they progress), irregularly-shaped, and may be ulcerated. It is easy to mistake sebaceous adenomas for warts, skin tags, or cysts.

Lipomas

Lipomas in dogs are benign, fatty tumors frequently found in middle aged to older dogs. You can often feel them just under the skin, and they can develop in any location or be any size. Since they are benign, usually the vet will not recommend removing lipomas unless they grow in areas that cause discomfort or other difficulties for your dog.

Like most masses, you or your vet cannot diagnose a lipoma based on sight or feel alone. If your dog has a soft subcutaneous mass, do not assume it is a lipoma, even if he or she has developed lipomas in the past. Although lipomas are benign, there are a number of malignant masses such as soft tissue sarcoma that can look and feel just like them!

Skin tags

As the name would imply, skin tags on dogs are an abnormal growth of skin which can be fairly flat, or longer and have a stalk. Usually, they are either black or pink and feel like skin. These masses are benign and generally don’t cause problems unless the dog is catching them on something or irritating them.

Mammary masses

Both male and female dogs can develop mammary masses, but they are most common in intact females or females who were spayed later in life. Approximately 50% of mammary masses in dogs are benign and 50% are malignant. Affected dogs tend to have one or multiple masses in the mammary chain which can have a variable appearance. Some are smooth and palpable under the skin while others are red, ulcerated, and painful.

And many, many more

Keep in mind that the masses listed above are just some of the types of tumors that dog parents can more commonly confuse with cysts. But this is far from an exhaustive list of masses in dogs.

What is the treatment for tumors in dogs?

The treatment for the various tumors we discussed varies depending on the tumor type. It may be fine to monitor benign tumors and only remove them if they start to cause problems. But if the tumor is cancerous, surgical removal is typically the treatment of choice. Plus, the vet or veterinary oncologist may recommend chemotherapy, radiation, or other adjunctive therapies in some cases.

How does the vet determine if the dog has a cyst vs. tumor?

By now you have probably picked up on the fact that it can be confusing to differentiate between a potentially cancerous tumor and a harmless cyst just by looking at the bump on your dog. Thus, there are two common procedures the vet may use to distinguish between a cyst and a tumor and to possibly obtain a more specific diagnosis—a fine needle aspiration and a biopsy.

Fine needle aspiration (FNA)

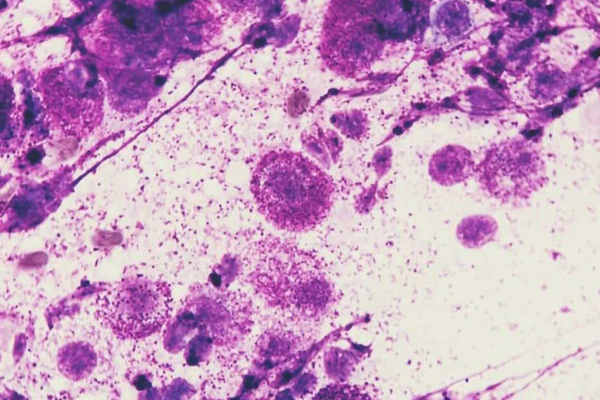

A fine needle aspiration is a fairly simple test that involves poking a small needle into the mass to collect some cells. The vet then spreads those cells onto a glass slide for microscopic evaluation.

Sometimes your veterinarian will look at those slides “in house.” Depending on the type of mass, he or she may be able to reach a diagnosis relatively quickly. However, other types of masses are harder to diagnose. So your vet may send those slides to a diagnostic laboratory for review by a veterinary clinical pathologist.

In some cases, even a clinical pathologist can’t definitively identify the type of mass on an FNA. Or your vet may feel that an FNA is not in your dog’s best interest. In those cases, the next step is often to biopsy the mass.

Biopsy

You may be familiar with humans having biopsies for a mass. As it turns out, the procedure is very similar for dogs. One major difference is that dogs don’t always understand that we are trying to help them, so they may or may not sit still enough for the vet to collect a sample while awake.

Thus, depending on the dog and the mass, the vet may perform the biopsy using local anesthesia, sedation, or general anesthesia. Your vet can help you determine which is most appropriate for your dog.

There are a few different types of biopsies your vet may perform:

- Excisional biopsy—This involves removing the entire growth plus variable margins of healthy skin around the mass.

- Punch biopsy—The vet uses a special tool to take a circular piece of the skin and mass. Usually the goal of a punch biopsy is to obtain a representative sample of tissue, but not necessarily the entire mass.

- Needle-core biopsy—This involves using a large-gauge needle to obtain a sample from a mass. The procedure is similar to an FNA, but obtains a larger tissue sample (though still a smaller sample than other biopsy techniques).

- Wedge biopsy or incisional biopsy—The vet will use a scalpel to cut into the tumor itself to remove a deep tissue sample.

No matter how the vet obtains the tissue, he or she will most likely send the sample to a diagnostic laboratory for histopathology. The lab will examine sections of the submitted tissue under a microscope to try to determine exactly what type of mass the dog has. As this can take time, it may be several days to weeks before you receive the biopsy results.

What should I do if I find a lump on my dog?

If you take nothing else from this article, remember this. Any new lump or bump warrants an exam with your vet. If the mass is not painful, ulcerated, or draining, it is probably not an emergency, but you should call your vet promptly to set up an appointment.

Depending on the situation, your vet may find a fine needle aspiration or biopsy to be the best first diagnostic step. He or she may be able to perform the FNA during that initial appointment. However, if your dog needs a biopsy, the vet will probably do so at a follow-up appointment because biopsies often require heavy sedation or anesthesia.

Once the vet has the results of the FNA or biopsy, he or she will work with you to devise a plan. Sometimes that is monitoring the mass. Other times it is surgery or referral to a veterinary specialist near you such as an oncologist.

Stay calm and work with your vet

If you find a lump on your dog, do not panic! I know this is easier said than done, but try to remind yourself that not all masses are bad news. Many skin bumps in dogs turn out to be cysts or benign tumors. By getting your dog to the vet promptly after discovering a mass, and working closely with your veterinarian, you can get some answers and give your dog the best chance for a good outcome.

Did your dog have a cyst vs. tumor?

Please comment below.

Gabby is a basset- black lab mix she developed a lump on her back a year ago and I have been monitoring it. It has grown to the size of a half- dollar in circumference and approximately 2” in height Started out as hard , now is soft . The fur is disappearing on top and I noticed some drainage. Called my vet, in the meantime I pressed on it and through a pencil size hole gushed greenish-white exudate , mostly thick fluidity with Peebles size white opaque chunks. When the vet called back I reported the above and he said most likely a sebaceous cyst. I drained it as much as possible until only a pale pink, possibly blood, fluid was expressed. . I’m using a non rinse antiseptic foaming solution to keep the opening from scabbing and giving Gabby an antibiotic , according to my vet’s directions. There is a penny size hard lump surfacing on her rib area . Do I follow protocol from present lump ? Barbara

Hi Barbara,

I am sorry Gabby is having these issues with her skin. Without knowing for certain that the new lump is also a cyst, I can’t recommend any type of specific treatment. There are certain kinds of tumors that if squeezed or damaged in any way, they can release several harmful substances into the body and cause a potentially life-threatening reaction. Your best bet is to have your vet take a look at this new lump and get an aspirate to evaluate under the microscope. Hoping for clear answers and favorable results!

My dog has soft movable lumps on her chest and abdomen. She doesn’t seem to have pain when they are probed. My vet attributes them to her cushings disease. She was started on trilostane the first week of July. She was tested 2 weeks after for trilostane’s effectiveness. I’ve been told it is working. My veterinarian thinks it may help to reduce the lumps in time. Do you have any suggestions here?

thank you, Sarah

Hi Sarah,

I am sorry your girl is dealing with the effects of Cushing’s disease. Without examining her myself, I can’t say for sure if the lumps are cause for concern. I always think it is best to get an aspirate of any new lumps and have them evaluated under the microscope (either in clinic or sent out for a pathologist to review). An aspirate can offer lots of information about the possible type of tumor and if it seems aggressive or benign. I hope you can get the answers you need to find a clear path forward. Wishing you and your sweet girl the best of luck!

Recently found a lump on my dogs neck. Took him to my vet and he did an aspiration and this results came back inconclusive. The vet then did a biopsy and the lump burst, so it turned into a removal. The vet thought the lump had grown since the original visit. I was glad that it burst while he was with the vet. Waiting on the results of the biopsy. Hoping it’s not cancerous!

Hi Melissa,

I am sorry your boy is dealing with this unknown lump on his neck. I am glad the surgery was successful and hope the pathologist’s results will be favorable. Feel free to leave an update and let us know how things are going. Best wishes to you and your sweet boy!

Our 13 year old standard poodle has developed what we are told by our vet is a benign lypoma. It is quite large and appears to be still growing. It is on his back and grown to be about the size of a slightly flattened tennis ball. Our vet has aspirated clear fluid from it and looked at it herself under the microscope. It moves around and is not solid and does not appear to bother him when touched. She does not want to remove it as she is hesitant to sedate him for fear of the side effects of the anesthesia and worries that he might not come out of it. Aesthetically, it is pretty unattractive. But it seems to be best to leave it given the possible side effects of trying to remove it. Save for a terrible set of teeth that our vet is also afraid to sedate him to have them cleaned and weak hind legs due to acl injuries years ago, he is in good spirits, eats well and voids well and loves to go on short walks. Should we be doing anything else to assure a correct diagnosis?

Hi Trish,

I understand your concern for your senior guy with this large mass on his back. I am not sure there is any other testing that can be done to get a definitive diagnosis without needing anesthesia or heavy sedation. If you wanted to consider pursuing surgery, your vet could offer referral to a specialty hospital where the anesthesia would be performed by a board-certified anesthesiologist. They have lots of experience with complicated cases and may be able to decrease the risk. Of course, if you decide to focus on quality of life instead, it is ok to monitor things at home and work with your vet to provide palliative care. Hoping you can get the answers you need to choose the best path for your sweet boy. Best wishes to you both!