Mitral valve disease in dogs (i.e. a leaky heart valve) is quite common in our senior companions. To help you understand this condition, integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby explains the anatomy and physiology behind mitral valve disease. And she discusses the stages, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis for mitral valve disease in dogs.

A few weeks ago, Annabelle, one of my favorite Chihuahuas (other than my own of course), came to see me for her semi-annual senior wellness visit. She was her usually lovely self. And everything was checking out great on her exam until I placed my stethoscope on her chest to listen to her heart. Immediately I heard the soft but distinct “woosh” of a heart murmur.

Thankfully, her lungs sounded great and her dad hadn’t noticed any coughing, difficulty exercising, or other signs related to heart disease. But I still recommended a chest X-ray and echocardiogram to evaluate her heart. Based on the presence of a new murmur and the fact that Annabelle was a senior small breed dog, I was pretty suspicious she was in the early stages of mitral valve disease in dogs.

- What is mitral valve disease in dogs?

- How does mitral valve disease in dogs occur?

- What are the stages of mitral valve disease in dogs?

- What are the symptoms of mitral valve disease?

- How is mitral valve disease diagnosed?

- What is the treatment for mitral valve disease in dogs?

- What is the prognosis for mitral valve disease in dogs?

- Take heart and partner with your vet

- Has your dog been diagnosed with mitral valve disease in dogs?

What is mitral valve disease in dogs?

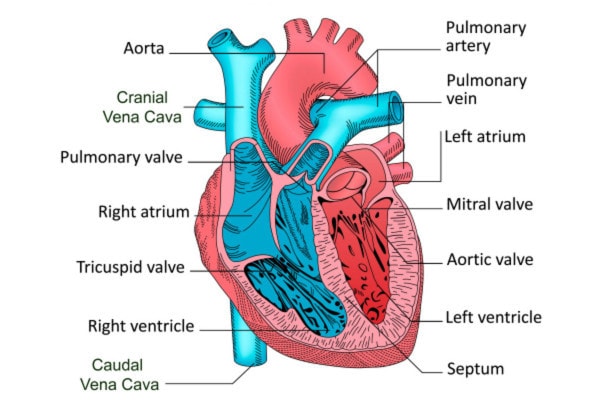

The term “mitral valve disease” refers to the degeneration, thickening, and subsequent leaking of the valve which separates the left atrium (i.e. top left chamber) and left ventricle (i.e. bottom left chamber) of a dog’s heart. The exact cause is unknown, but it is thought that there may be a genetic component.

Which dogs get mitral valve disease?

In general, smaller dogs (under 20 kilograms or 44 pounds) are more likely to develop MMVD. The following dog breeds are prone to mitral valve disease:

- Cavalier King Charles Spaniels

- Dachshunds

- Chihuahuas

- Cocker Spaniels

- Fox Terriers

- Mini Schnauzers

- Mini and Toy Poodles

- Pomeranians

- Whippets

- Yorkshire Terriers

However, larger dogs can also develop mitral valve disease. And they tend to have a faster disease progression compared with small to medium-size dogs.

Additionally, mitral valve disease is more common in males than in females. And it is typically diagnosed in older dogs, with an average age at the time of diagnosis of 10.7 years. The exception to this is Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, who tend to develop mitral valve disease significantly earlier in life.

How common is mitral valve disease in dogs?

Mitral valve disease is the most common heart disease in dogs, accounting for roughly 75% of cases of canine heart disease in North America. However, dogs can also develop tricuspid valve disease, which is the same condition, just on the right side of the heart instead of the left.

Tricuspid valve disease is estimated to occur in 30% of dogs who also have mitral valve disease. For the purposes of the article, we will mostly talk about mitral valve disease. However, many of the same principles hold true for tricuspid valve disease.

What are some other names for mitral valve disease?

Before we go any further, I want to clear up some terminology. You may also see mitral valve disease be referred to as myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD). The term “myxomatous” refers to thickening, so it is a good descriptor of what is going on. Alternatively, the condition may also be called:

- Mitral valve insufficiency

- Mitral valve endocardiosis

- Degenerative mitral valve disease

- Mitral valve regurgitation

However, mitral valve disease is NOT the same condition as:

- Mitral valve dysplasia (i.e. congenital malformation of the mitral valve which may cause the valve to leak)

- Mitral valve stenosis (i.e. congenital narrowing of the mitral valve)

- Valvular endocarditis (i.e. inflammation of the heart valves which may correspond with infection)

Unlike these conditions, mitral valve disease involves degeneration of the valve over time.

How does mitral valve disease in dogs occur?

Healthy heart valves are made of thin segments of connective tissue. But in mitral valve disease, the cells that make up the valve apparatus, as well as the framework around the cells (i.e. extracellular matrix), change. This leads to thickening and deformation of the valve and alterations in valve motion and closing.

The mitral valve leaks

Normally, when the mitral valve opens, blood flows from the atrium to the ventricle. Then the mitral valve tightly closes so that as the heart pumps, the blood will continue its forward motion out of the ventricle and to the body.

If the valve doesn’t seal completely, blood can shoot backwards into the atrium when the heart contracts instead of leaving the ventricle via the aorta (i.e. huge vessel that sends blood to the body). This backflow of blood is called mitral regurgitation. The resulting turbulent blood flow is what creates the “woosh” sound of a heart murmur. And having extra blood going back into the atrium can create issues for the heart.

The heart tries to compensate

Early on in the disease, the heart can still usually manage to function fairly well. But as more and more blood goes backwards instead of forwards, the heart must work harder to compensate. The left atrium and left ventricle may become enlarged due to the increased volume and increased work.

Plus, the body will activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) to retain sodium and water. This boosts the overall blood volume, which accomplishes the goal of getting enough blood out to the body. But it also further overloads the heart. (This bit of information becomes more relevant when we discuss treatment.)

The heart eventually fails

If the regurgitation continues to worsen or the dog has other complications (e.g. an arrythmia), the time may come when the heart is no longer able to keep up with moving blood through the left atrium and ventricle. Blood may start backing up in the vessels in the lungs (the location before the left atrium). And fluid will leave the blood vessels and accumulate in the lungs, leading to congestive heart failure in dogs.

This sequence of heart disease that eventually progresses to heart failure usually occurs gradually over time. However, it is possible for a dog to rapidly go into severe heart failure if they rupture one of the components of the apparatus that anchors the valve leaflets in place (the chordae tendineae and papillary muscles). Such an event would lead to massive regurgitation that the body doesn’t have time to compensate for.

What are the stages of mitral valve disease in dogs?

While we have discussed mitral valve disease as a continuum, it is also possible to break it into discrete stages. Doing so is helpful because it allows veterinarians and veterinary cardiologists to discuss mitral valve disease with the same language. And it means that each stage can have its own diagnostic and treatment guidelines. The stages of mitral valve disease in dogs, as set forth by the ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs are as follows:

- Stage A —The dog is at a higher risk of developing MMVD due to his or her breed, but the heart has not yet undergone any structural disease. This group would include Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and Dachshunds as well as other at-risk breeds.

- Stage B—The dog is asymptomatic but has structural heart disease (e.g. changes in the mitral valve and mitral regurgitation).

- Stage B1— There are no remodeling changes seen on imaging (e.g. X-rays or echocardiogram).

- Stage B2—There is evidence of heart remodeling (e.g. an enlarged left atrium noted on X-rays).

- Stage C—The structural heart disease is now severe enough to cause heart failure signs. Affected dogs are responsive to standard heart failure medications and doses.

- Stage D—The dog is in end-stage mitral valve disease. There are signs of heart failure, and there is no response to standard medications at the typical dose. Treating this stage may require hospitalization and/or intensive or novel therapies.

Additionally, there is also an unofficial stage that is not in the guidelines, Stage BC. Vets may use it to denote dogs who have structural heart disease and are coughing from compression of their main airways (i.e. bronchi) but are not in heart failure.

What are the symptoms of mitral valve disease?

As you may have noticed when we were discussing the stages of MMVD, dogs often start out being asymptomatic. The veterinarian hearing a heart murmur may be the first indication that anything is going on with your dog’s heart. However, as the mitral valve disease worsens, the dog may start becoming symptomatic.

One common sign is coughing, especially at night. For example, dogs with Stage BC disease will cough due to the enlarged heart compressing the airway. The cough occurs because anatomically, the main bronchi sit right above the left atrium. So as the left atrium enlarges, it may push on the bronchi, triggering a cough.

However, other dogs with mitral valve disease may have concurrent chronic bronchitis in dogs. This can also make them cough. Or dogs with advanced mitral valve disease may be coughing due to pulmonary edema and heart failure. Thus, a cough in a dog with MVDD can mean a variety of things.

In addition to a cough, dogs with worsening mitral valve disease may show other signs such as:

- Being a lethargic dog

- Exercise intolerance (e.g. not wanting to play, becoming tired quickly with “normal” exertion)

- Dog is breathing fast (i.e. tachypnea)

- Labored breathing or respiratory distress

- Collapse (i.e. syncope, which is not the same as seizures in dogs)

- Dog not eating

- Pale or blue gums

- Standing with neck outstretched and elbows pointed away from sides (i.e. orthopnea)

If your dog is showing some of the more mild clinical signs (e.g. lethargy, slight exercise intolerance, occasional coughing), you should schedule a regular appointment with your vet. But if your dog is turning blue, collapsing, or struggling to breathe, make an emergency vet visit immediately. Respiratory distress is always an emergency and can be a matter of life or death.

How is mitral valve disease diagnosed?

Depending on if your dog is stable or not, the diagnostic process and order may vary some. But in general, the following tests help gather more information and make a diagnosis of mitral valve disease:

Physical exam

As part of the examination, the vet will listen carefully to the right and left sides of the chest for a heart murmur in dogs. Regurgitation of blood through a leaky mitral valve can cause a murmur that is loudest on the left side of the chest. But other heart conditions can also cause a murmur, so a murmur isn’t diagnostic for mitral valve disease on its own.

The loudness of the murmur can, however, give some clues as to which stage of mitral valve disease a dog may be in. Heart murmurs are graded from I (softest) to VI (loudest). Usually a quieter murmur goes with less severe disease, and as the loudness increases, so does the stage. To be qualified as Stage B2 mitral valve disease, the murmur must be at least a III out of IV. And dogs with a stage V or VI murmur are more likely to be stage C or D.

In addition to listening for a murmur, the vet will also be evaluating the dogs heart rate and rhythm. Dogs with mitral valve disease sometimes have an increased heart rate as a compensatory mechanism. And occasionally they may have an arrythmia as well.

Finally, the vet will evaluate the lung fields on both sides of the chest for any crackles. This sound typically indicates that fluid is building up in the lungs due to congestive heart failure. However, dogs with early congestive heart failure may not have crackles, so normal lung sounds don’t rule out congestive heart failure completely.

Chest X-rays

The veterinarian will often recommend taking a series of chest X-rays. This is a useful imaging modality for several reasons. First off, it allows the vet to evaluate the size and shape of the heart. Dogs with 2A or lower mitral valve disease won’t have any noticeable cardiac changes.

But dogs in stage 2B and above may have an increased vertebral heart score (i.e. measurement of heart size that is useful for detecting heart enlargement) and an enlarged left atrium or ventricle. These findings can also be compared to future X-rays to track the progression of the disease.

Additionally, X-rays can be helpful for looking at the dog’s lungs. The vet may be able to determine if the left atrium appears to be compressing the main bronchi. And he or she can evaluate the lungs for signs of congestive heart failure (or other causes of coughing or respiratory symptoms like bronchitis or pneumonia).

Echocardiograph

It is recommended that every dog with a heart murmur have an echocardiogram (i.e. ultrasound of the heart). This test is well-suited for evaluating the function of the valves, size of the chambers, and the amount of blood that is regurgitating through the valve. Plus, in addition to diagnosing mitral valve disease, it can detect other cardiac problems.

However, not all general practice veterinarians are equipped to perform echocardiograms. This means that the dog may need to be referred to a veterinary cardiologist. Or a traveling ultrasonographer may need to come to the practice to perform the echocardiogram.

Blood pressure measurement

The vet may recommend checking your dog’s blood pressure. This helps establish a baseline for what is normal for your dog. And it allows the vet to detect hypertension in dogs (i.e. high blood pressure).

Electrocardiograph

In order to assess your dog’s heart rhythm, the vet may recommend an electrocardiograph (ECG or EKG). Most dogs with mild MMVD don’t have arrhythmias, but they do occasionally occur in larger dogs or more severe disease.

NT-proBNP

In some situations the vet may recommend a blood test called NT-proBNP. This test measures a biomarker that, when elevated, suggests that the heart muscle is being stretched (as would happen with regurgitation from mitral valve disease).

The veterinarian will work with you to determine which of these tests are appropriate for your dog’s situation. As alluded to, there may be situations where the vet starts the cardiac work-up in-house and then refers your dog to a veterinary cardiologist for further testing or treatment.

What is the treatment for mitral valve disease in dogs?

After diagnosing your dog with mitral valve disease, the veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist will formulate a treatment plan based on your dog’s symptoms and disease stage.

Stages A and B1

Dogs with stages A and B1 mitral valve disease don’t need any medications or special foods.

Stage B2

However, for stage B2 dogs, research has indicated that the medication pimobendan (Vetmedin®) can delay the amount of time it takes for mitral valve disease to progress to end-stage heart failure. Plus, some veterinarians recommend an ACE inhibitor like enalapril for dogs to counteract the activation of the RAAS system (which we discussed earlier). These dogs may also benefit from a low sodium and moderate protein food.

Stage C

Some stage C dogs may require hospitalization in order to get their congestive heart failure under control. While in the hospital, they may receive oxygen therapy, pimobendan, and diuretics like furosemide (Lasix®). Plus, if needed, the vet may administer sedatives to decrease anxiety, medications to regulate blood pressure, or other medications.

At home, dogs with stage C heart failure usually continue to take diuretics (e.g. furosemide and/or spironolactone) plus pimobendan and enalapril. Some may also need medications to control heart arrhythmias or coughing.

Stage D

By the time dogs reach stage D, their heart failure isn’t responding to the medications and/or doses used for Stage C. Sometimes these dogs can be hospitalized and treated with diuretics and other intensive or novel treatments. And they may also be able to go home on higher doses of furosemide and pimobendan, or other diuretics or medications.

However, at this point (if not before), dog parents may also need start thinking about when to euthanize their dog. Talking to the veterinarian and using a quality of life scale for dogs can sometimes provide clarity in this situation.

What about valve surgery?

Since people can have mitral valve surgery, it only makes sense that dog parents may wonder if it is an option for canine MMVD. As it turns out, there are a few specialty centers and teaching hospitals that are performing surgical repair of a dog’s mitral valve. However, the surgery is extremely expensive and is not widely available at this time.

Are there natural treatments for mitral valve disease?

Additionally, some dog parents may be interested in natural or holistic treatments. While there aren’t any supplements or foods that can prevent or treat mitral valve disease, there are some natural ways to support the heart.

As mentioned earlier, the best dog foods for mitral valve disease are diets that are low in sodium and low in phosphorus. They should also contain a moderate amount of protein, and ideally a low fat content. Some pet food companies have veterinary diets specifically made for heart health. Or, you can look for a recipe for a veterinary nutritionist-approved homecooked diet for dogs with heart disease.

Additionally, omega-3 fatty acids for dogs, such as those found in fish oil, can prevent inflammation at the level of the heart. And they can reduce the risk of arrhythmias. Therefore, dogs with heart disease can benefit from an omega-3 supplement.

How can I care for my dog with MMVD?

With all this discussion about medications, supplements, and foods, I understand that caring for a dog with mitral valve disease can feel a bit overwhelming. But I know you can do it! To help provide some guidance and support, I’ve compiled the following tips:

Medications

- Give all medications as directed and do your best to not accidentally skip any doses. Especially by the time the dog is in stage C or D, the heart medications are critical for helping reduce fluid in the lungs and improve heart function.

- Pay attention to when your dog needs medication refills so you don’t accidentally run out.

Monitoring

- Get in the habit of monitoring your dog’s sleeping respiratory rate. You can do this by counting the number of times your dog breathes (inhale plus exhale is one breath) in 15 seconds then multiplying the number by four. Most normal dogs have a sleeping respiratory rate of less than 30 breaths per minute. If you notice that your dog’s sleeping breathing rate is above 30, or it has changed from his or her normal baseline, reach out to your vet. This could be an indication that your dog’s heart disease is progressing.

- Keep all follow-up appointments with your vet and allow him or her to perform the necessary diagnostics to determine the status of your dog’s MMVD.

- Reach out to your vet whenever you have questions or notice a change in your dog’s symptoms. You know your dog better than anyone, so you are the best person to detect subtle changes.

Precautions related to exercise and environmental conditions

- Be mindful of how you exercise your dog. Regular exercise is still good for many dogs with MMVD, but you have to be a bit more careful about how long you walk or how strenuous the exercise is.

- Pay attention to the ambient temperature and humidity. Dogs with heart disease may have more trouble breathing when it is hot or humid. And they are at increased risk of becoming an overheated dog or, worse yet, developing life-threatening heat stroke in dogs. Therefore, it is advisable to take measures to keep your dog cool in the summer (and other warm times of the year).

What is the prognosis for mitral valve disease in dogs?

The outlook for dogs with MMVD varies greatly depending on the stage, severity of the murmur, and other factors (e.g. presence of an arrythmia, degree of atrial and ventricular enlargement, NT-proBNP levels, dog size, etc.).

However, overall, dogs who are in stages B1 and B2 have a median survival time (MST) of 588 to 649 days, depending on the study. This means that 588 to 649 days after the diagnosis, 50% of dogs are still alive.

One study indicated a MST of 220 days for dogs with stage C disease. And Stage D disease, as you may imagine, has the worst prognosis, with a MST of 52 days.

On the other hand, in a study of 92 dogs who had mitral valve surgery, the MST was 825 days, 771.3 days, and 733.6 days for Stages B2, C, and D respectively.

Remember though, these are just average survival times. This means that some dogs will live longer than these numbers predict while others may succumb to their disease relatively quickly. Your vet or veterinary cardiologist may be able to give you a better idea of what to expect for your dog’s particular case of MMVD.

Take heart and partner with your vet

Mitral valve disease is common in senior dogs, but knowing that doesn’t make it any less stressful when it’s your dog receiving the diagnosis. Hopefully though, the information I have shared, plus your discussion with the veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist, can help you better understand what is going on with your dogs heart.

While there is always that scary possibility of heart failure in the future, many dogs with mitral valve disease can have a great quality of life, especially in the early stages. And the medications we have available now can often help prolong the time until the onset of heart failure and manage heart failure effectively for a period of time. So don’t lose heart. Instead, enjoy spending time with your dog and work closely with your vet to optimize your dog’s care.

Has your dog been diagnosed with mitral valve disease in dogs?

Please share his or her story below.

I have a 13 years old Pomeranian mix girl. She’s got great appetite, sleeps great, is very active, loves her walks and her play time. In 2023 the vet found a stage 2 heart murmur but said nothing needed to be done. In June of this year, a different vet said the murmur seemed almost a stage 3 and suggested having a consultation with a cardiologist. She was referred and I couldn’t get her in until the end of October. I am very nervous as the vet mentioned the possibility of Mitral Valve Disease and I have read early diagnosis is key. Is there any chance that she could be stage C or more without any symptoms? I guess I am looking for reassurance that it is okay to wait a couple more months to get her specialty care. Thank you.

Hi Laeti,

I understand your concern for your senior girl as you wait for your appointment with the cardiologist. Without examining her myself, it is hard to offer specific conclusions about the stage of her disease. I think you may be confusing the grade of the murmur (grade 1 to 6 with 6 being the worst) with the stage of mitral valve disease (stage A to D). A murmur can occur at any of the valves in the heart. The mitral valve is just one of these but is the one most commonly affected with a murmur. Since your girl does not have any symptoms other than the murmur, I would assume she is a stage B, but again the specialist will confirm this for you. As long as her condition remains stable, and you are not seeing any new symptoms emerge, I think it will be fine to wait another month for the appointment with the cardiologist. Hoping your girl is still feeling well and living her best life. You are doing a great job taking care of her. Praying for a positive outcome and keep up the good work.

Hello my baby (11 years old) was diagnosed with CHF with a heart murmur and MVD. She is doing pretty well on her meds. However we were looking into the TÈER procedure. Do you happen to know if this procedure is done in Florida, other that UF, as they are completely booked?.

Thank you in advance!

kathy

Hi Kathy,

I am sorry your senior girl is living with this difficult condition. I am glad she seems to be doing well on her medications. Unfortunately, I don’t have any information about where this procedure is offered. Your vet should be able to look up other specialists in your area/state and find out if they will perform this surgery with a referral. Hoping you can get an appointment soon and ensure your pup gets the care she needs. Best wishes to you both!

My dog went from a stage two heart murmur to a stage four within a month. And the electrocardiogram showed an enlarged heart and enlarged atrial valve. I don’t really understand what this means. They put him on medicine because he has a severe cough.Pimobendan and cerenia. I don’t know the name of this disease is prognosis or how long his survival rate could be. I’m terribly worried because my other dog has endocardiosis and I’ve been struggling to keep him alive for the past three years.

Hi Jodie,

I am sorry you are facing this scary situation with your pup. Without knowing all the details and playing a personal role in your dog’s medical care, it is hard to offer specific conclusions and advice. This could be dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) but again, I can’t know for sure. Please reach out to your vet and make sure they know you need more information and that you are not clear about what is happening. Be honest and transparent and ask for details. You can also ask for a consultation with a veterinary cardiologist if needed. Praying for strength and comfort as you navigate this difficult path. Bless you and both of your boys.

My Dog Taschi was diagnosed with a Heart murmur and was placed on medication. She was at first diagnosed with a 6 out of 6 murmur, but the Cardio Doctor who did some tests said that she was a 4 out of 6 which gave me some hope. She is a Lhasa Apso, and interestingly my Tibetan Terrier was also diagnosed with a murmur as well. He is a year older than Taschi but according to various Vets who have seen him the murmur ranges from 2 to 4 out of 6. I will pursue a closer diagnosis for Ceba when I can get the funds for another Cardio exam. At one point this past summer while at an emergency visit with Ceba for a possible toadstool consumption, I read an article in the AVMA journal about several grain-free dog foods that were causing severe heart valve problems, and I immediately started switching out what I was feeding to a dog food that contained Taurine. I would like to read more about this connection between grain-free food and heart valve problems. Would you have any articles available…or is this a fairly new observation? Please let me know when you have an opportunity to read about my experience.

Hi Karyl,

I am sorry both of your pups are dealing with heart issues. It may not have been related, but I think it is wise you have discontinued the grain free diets out of an abundance of caution. Yes, the grain free diets and heart disease issue is still fairly new. A link between the two was suspected a few years ago but the cause remained unknown. We didn’t know if the heart disease was from a lack of grain or due to the inclusion of other carbohydrate sources that were being used to replace the grain. It has only been in the last year or two that scientists have started investigating a link with the amino acid Taurine. It seems as though the biggest issue is with grain free diets that contain pea products such as pea protein, pea fiber, etc. Of course, all this is still being investigated and it is possible they will find out different/new information as time goes on. Rest assured once we have concrete accurate information backed by research, we will be sure to pass that along to our readers!