Uveitis in dogs (i.e. inflammation of the uvea, a collection of structure inside the eye) can cause red, cloudy, or painful eyes. Integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby explains the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of uveitis to help you navigate this diagnosis with your dog.

You can tell a lot about what a dog is thinking by looking at his or her eyes. A hungry pup might stare you down while you try to eat your lunch as if the intensity of his or her gaze can coerce you into “accidentally” dropping a piece or two. Or an excited dog’s eyes might track your every move as you put your shoes on and grab his or her leash in preparation for a walk.

Your dog’s mood isn’t the only thing that his or her eyes can show you, though. Sometimes the appearance of the eyes can be a sign of a pet health problem. For example, if the eyes appear red, cloudy, or squinty, this may indicate your dear dog has uveitis in dogs.

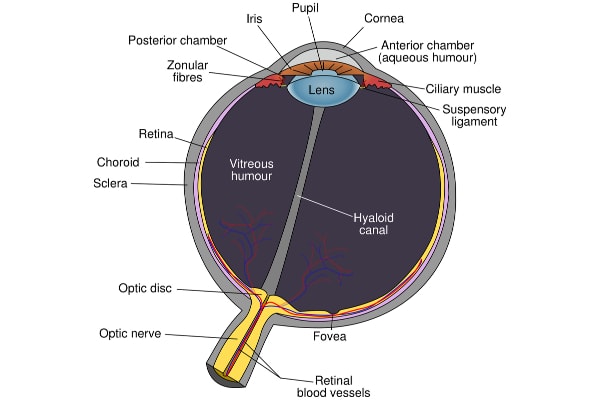

In order to explain what uveitis is, we need to start with a quick anatomy lesson.

Eye anatomy 101

The cornea (i.e. the front surface of the eye) is sort of like the windshield for the eye. Normally, it is completely clear and the surface is moist and a little shiny. Deep to that, you will see the colored portion of the eyes (i.e. the iris) with a black hole in the center (i.e. the pupil). Behind the pupil, there is a clear disc-shaped structure called the lens.

The lens changes shape in order to alter the way light hits the retina. This nerve cell layer is the innermost of the three layers that make up the back of the eye. The other two are the choroid, which is the blood vessel-rich middle layer, and the sclera, which is the outermost white portion of the eye.

Two chambers compose the front of the eye—the anterior chamber (in front of the iris) and the posterior chamber (between the iris and the lens). Aqueous humor, a clear watery fluid, fills both chambers. The portion of the eye behind the lens is filled with the jelly-like vitreous humor, which should also be clear.

What is uveitis in dogs?

Now that you have an idea of the anatomy of the eye, it is time to introduce one more structure—the uvea or uveal tract. It is made up of three parts (two of which you are already familiar with):

- Iris

- Ciliary body (which produces the aqueous humor)

- Choroid

Based on knowing that “itis” means inflammation, you can probably deduce that uveitis is an inflammation of the uvea.

Types of uveitis

There are three different types of uveitis—anterior uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis. Each type of uveitis is classified by which uveal structures are affected:

- Anterior uveitis—inflammation of the iris and ciliary body

- Posterior uveitis—inflammation of the choroid

- Panuveitis—inflammation of all three structures

Anterior uveitis in dogs is the most common of the three types while panuveitis is typically the most severe.

What causes uveitis in dogs?

Uveitis can be a tricky illness because there are so many different causes. Rather than list every single one, we will discuss some broad categories and group them based on whether they occur from outside the body (i.e. exogenous) or within the body (i.e. endogenous).

External causes

Exogenous causes of uveitis occur less frequently than endogenous ones, but they are still important to talk about.

Eye injury

It is possible for uveitis to occur secondary to an eye injury. For example, the delicate cornea can suffer a cut or injury known as a corneal ulceration. When corneal ulcers in dogs are deep enough to affect the inner parts of the eye, the uveal structures may become inflamed.

Damaging substances

Harmful chemicals such as pesticides and cleaners (especially very acidic ones) can trigger uveitis when they contact the eye. Also, sometimes UV radiation from sunlight can cause uveitis, even on overcast days. If your dog frequently spends time outdoors, he or she may need special goggles (i.e. Doggles) to protect his or her eyes.

Internal causes

More cases of uveitis tend to be the result of events or diseases that are occurring within the body.

Infections

The most common cause of uveitis in dogs is various types of infections. These can be:

- Viral infections like distemper

- Bacterial infections such as leptospirosis and Brucella canis

- Fungal infections like blastomycosis and histoplasmosis

- Tick-borne diseases in dogs like Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis

- Parasitic infections like toxocariasis (i.e. roundworm infestation)

While uveitis itself is not contagious, some of these infections can spread from one dog to another.

Systemic diseases

High blood pressure (i.e. hypertension in dogs) and systemic diseases like diabetes mellitus can also contribute to uveitis. Dogs with diabetes mellitus are at increased risk of developing cataracts in dogs, opacities that form within the (normally) crystal-clear lens. In advanced cataracts, proteins can leak from the diseased lens and cause lens-induced uveitis. By that same token, high blood pressure can worsen protein leakage from the lens.

Eye diseases

As previously mentioned, corneal ulcers and cataracts (which have a variety of causes) may trigger uveitis. Plus, other intraocular problems like lens luxation (i.e. a lens that has moved from its normal location) or retinal detachment can also incite uveitis.

Congenital disorders

Golden Retrievers, and occasionally other dogs, can suffer from a congenital disorder called Golden Retriever pigmentary uveitis (GRPU). It is not known exactly why it occurs, but young Golden Retrievers may suddenly develop fluid-filled cysts behind their irises. The cysts may become larger or increase in number. Eventually this causes the pressure within the eye (i.e. intraocular pressure or IOP) to increase.

Increased eye pressures are referred to as glaucoma in dogs. Unfortunately, this secondary glaucoma (i.e. glaucoma occurring secondary to a medical condition) can cause blindness long term.

Miscellaneous conditions

- Autoimmune disorders like uveodermatologic syndrome can trigger uveitis when a dog’s body creates antibodies (i.e. immune system proteins) that target cells inside the eye.

- Tumors that form within the eye such as uveal melanoma can start out causing uveitis. Then they may progress to more intense illness as the tumor becomes larger and/or destroys structures within the eye.

- Cancer in other parts of the body, such as lymphoma in dogs can also trigger uveitis.

What are the symptoms of uveitis in dogs?

As you can probably gather from this list of causes, dogs with uveitis can have a range of symptoms. Some are related to the uveitis and others are related to the underlying cause.

Uveitis symptoms in dogs can manifest in very subtle ways, and they may vary based on the intensity of the uveitis. In some cases of uveitis, you may notice:

- Mild redness of the conjunctiva (i.e. hyperemia)

- Redness that affects the whites of the eyes (i.e. episcleral injection)

- Eye discharge

- Excessive squinting (i.e. blepharospasm), which can indicate the eye is painful

- The eye appears smaller and more sunken in due to a drop in intraocular pressure

- Elevated or prominent third eyelid (i.e. triangle of tissue in the inner corner of the eye)

- Constricted pupils

- Light sensitivity (i.e. photophobia)

- Cloudiness in the anterior chamber (i.e. aqueous flare) or cornea (ie. corneal edema)—most of the time, uveitis results in aqueous flare, but corneal edema is possible because disorders that cause corneal edema can sometimes also lead to uveitis.

- Blood or pus in the aqueous chamber, which may settle to the bottom of the chamber

If the uveitis is secondary to a systemic problem, you will likely see bilateral uveitis. This means that the uveitis impacts both eyes instead of just one. You might also see clinical signs that accompany the condition that caused the uveitis. Those symptoms can range from swollen lymph nodes in dogs to lameness, vomiting, tremors, or increased thirst in dogs.

There are also some instances where you will see other (and perhaps vague) clinical signs before you see any ocular changes. This is why many veterinarians agree that uveitis can be challenging to diagnose and difficult for dog parents to spot.

How is uveitis in dogs diagnosed?

If your vet suspects your dog could have uveitis, he or she will probably start the diagnostic process with a good nose-to-tail physical examination. Part of that involves using an ophthalmoscope to evaluate the inside of the dog’s eyes. Based on the ophthalmic exam, your veterinarian may be able to reach a preliminary diagnosis of uveitis.

When diagnosing anterior uveitis specifically, the vet watches for:

- Swelling of the iris (i.e. iris bombe)

- Discoloration of the iris

- Aqueous flare (a hallmark sign)

- Miosis (i.e. constricted pupils)

- Corneal edema

- Blood or pus in the aqueous chamber of the eye

When trying to diagnose posterior uveitis, the vet may use the ophthalmoscope to look for:

- Decreased reflectivity of the tapetum (i.e. the shiny part in the back of the eye that gives your dog “glowing” eyes in all of your flash photos)

- Bleeding or swelling in the back of the eye (especially from the retina)

- Distended blood vessels

- Retinal detachment

- Optic nerve atrophy

Also, the veterinarian may potentially measure your dog’s intraocular pressures with a tonometer. If the IOPs are low, this makes a diagnosis of uveitis very likely.

To help look for evidence of systemic disease, your vet may recommend blood and urine testing, X-rays, chest or abdominal ultrasounds, biopsies or other tests. Your vet will select the appropriate tests based on your dog’s history, symptoms, and physical exam findings.

Referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist

Sometimes there may be situations where your vet recommends having a board-certified veterinary ophthalmologist evaluate your dog’s eyes. These veterinarians have undergone years of specialized training that focuses on eye conditions. Plus, an ophthalmologist has access to specialized tools that help him or her examine the individual structures of the uvea.

What is the treatment for uveitis in dogs?

With so many varied causes and symptoms, and since it is such a diagnostic challenge at times, you’re probably wondering, “Can uveitis be cured?” The good news is that in most instances, it can! And like most health issues in veterinary medicine, successful treatment of uveitis in dogs will depend on finding and addressing the underlying cause.

Since uveitis can be a painful condition, your vet may recommend topical and oral medications to reduce inflammation and relieve pain. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatories like diclofenac and flurbiprofen are great options.

Or, if the vet thinks a steroid would work better, the uveitis medication of choice might be prednisone for dogs or dexamethasone. However, those topicals can cause a corneal ulcer to worsen. This means your vet will not prescribe them in cases of suspected or known ulcers.

Typically, the vet will only recommend oral antibiotics when the dog has a systemic infection (e.g. Lyme disease in dogs, leptospirosis, etc.). The vet may prescribe immunosuppressive medications if he or she diagnoses a dog with an autoimmune disease or has ruled out other causes of uveitis.

For cancer patients and dogs with severe uveitis, treatments might not work in the beginning. If your vet has exhausted most medical options, he or she might talk to you about surgical options such as repairing a corneal tear or removing the eye in its entirety (i.e. enucleation) to make your dog more comfortable.

If the opposite eye is healthy, submitting the enucleated eye for testing may help determine a definitive diagnosis. Plus, it may give your vet the information needed to prevent disease in the opposing eye.

What is the prognosis for uveitis in dogs?

Dogs with uveitis may show improvement in 24 to 48 hours from the start of treatment. However, it may take five to seven days for any cloudiness in the eye to disappear. You will need to bring your pup back to the vet every one to four weeks to ensure that treatment is working. These visits may involve repeating tests, rechecking the IOPs, or using other methods to track the status of the uveitis and the underlying condition.

Overall, the prognosis is going to depend on the underlying cause, the severity of the uveitis, and how fast treatment is started. Unfortunately, cases of severe uveitis (especially panuveitis) may result in secondary glaucoma or permanent blindness.

Talk to your veterinarian

Uveitis can be painful for dogs and concerning for dog parents. Thankfully, mild to moderate cases may respond well to treatment, especially when the uveitis is caught quickly. If you think something is “off” with your dog, don’t hesitate to make an appointment with your veterinarian.

Sometimes uveitis and its underlying cause can be a bit difficult to pin down. So be patient with your vet or the veterinary ophthalmologist as he or she works through the diagnostic process. Remember that you are all pursuing the same goal—a happy, healthy life for your dear dog.

Do you have experience with uveitis in dogs?

Please comment below

Our dog has been diagnosed with uveitis and is being treated but does sunlight hurt their eyes

Hi Debbie,

Most dogs do experience sensitivity to sunlight when dealing with uveitis. You may see them squinting or avoiding bright light. This is a great question! Thanks for asking.