When there is a tumor on a dog’s paw, it may be malignant, benign, or not actually a tumor at all. So how do you tell the difference? Integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby answers that question and discusses three categories of lumps on a dog’s paw so that dog parents will know what to do if they find a tumor on their dog’s paw.

Tumors can appear almost anywhere on a dog’s body, including his or her paws. But the good news is that not all bumps on a dog’s paw are cancer. Some of them, while unsightly and sometimes uncomfortable for your dog, aren’t inherently dangerous.

The difficult part is that it can be almost impossible to tell which lumps on a dog’s paw are cancerous just by looking at them. So what should you do if you are doing your weekly 5-minute dog wellness scan and you notice a tumor on your dog’s paw? Make an appointment with your vet, of course!

How can the vet determine the origin of a tumor on a dog’s paw?

At the veterinary clinic, your dog’s vet will carefully examine the bump you found. Plus, he or she will do a complete physical exam on your dog to look for any other lumps or health issues. Then, he or she will most likely recommend some different diagnostics to figure out what kind of tumor is on your dog’s paw (or if it is even a tumor at all).

It would be amazing if all vets got a pair of “cytology glasses” during vet school so that we could look at a lump and immediately know what it is. However, we didn’t get that, or X-ray vision, or any of those other handy vet superpowers. But we did learn how to take a sample of cells from a mass and examine them under the microscope (or ask a veterinary pathologist to weigh in).

Usually, when it comes to suspected tumors, the vet will want to perform a fine needle aspirate, a biopsy, or both.

Fine needle aspiration

One of the quickest and least invasive methods of identifying the type of tumor is a fine needle aspiration (FNA). As the name would imply, the vet inserts a small needle into the mass several times to collect some cells. Then, he or she spreads the cells on a slide, stains them, and examines them under a microscope. (Or the vet may send the slide to a diagnostic lab for a pathologist to review.)

This can often, but not always, give the vet a good idea of what type of cells make up the mass. For example, mast cell tumors are usually easy to recognize because the cells often have distinct blue granules. Or, if the aspirate yields thick, cheesy material that is mostly cellular debris, the dog may have a sebaceous cyst.

However, the FNA doesn’t always reveal the identity of the mass. This can be the case because some masses don’t exfoliate well (i.e. it is hard to get cells out of them). Or the aspirate may contain cells or debris that don’t point to a definitive tumor type. Plus, some masses are just too small or too flat to accurately sample with a needle.

Biopsy

In situations where the FNA isn’t definitive, the vet may suggest moving to a biopsy. Additionally, if the vet removes a mass, he or she may also recommend sending it in for a biopsy. This is often the case even if the vet is pretty sure of the identity of the tumor based on the FNA.

Biopsies are so important because they allow the veterinary pathologist to look at a whole piece of tissue, rather than a collection of cells.

An FNA is sort of like blindly plunging your hand into a layer cake and pulling out a handful of crumbs. You can guess what kinds of cake it contains based on the crumbs. But you don’t know how the layers are arranged. And you don’t know if there is a chocolate layer and a vanilla layer, or if the two flavors are swirled together in each layer.

On the other hand, a biopsy is like cutting a full slice of the cake. You can see each layer distinctly and look at the filling between the layers. This gives you a much better idea of what the whole cake, and each layer, was really like.

Why do an FNA and a biopsy?

Now that I have made everyone hungry for cake, let’s wrap back around to tumors. The FNA is a valuable starting test because it is non-invasive. And it can funnel the masses into the “probably XYZ type of noncancerous tumor” category or the “most likely XYZ cancerous tumor” category. That information helps the vet find the best course of treatment.

Then, if the recommendation is to remove the mass, the biopsy gives the next level of information. It helps the vet definitively know the identity of the tumor (because sometimes it isn’t what the FNA suggested). And, in the case of some tumor types, the pathologist can grade and stage the tumor. This helps give an idea of the prognosis. Finally, seeing whole slices of tissue also allows the pathologist to determine if the surgery removed the entire tumor. All of this information will help the vet to further refine the treatment and monitoring plan.

What are the types of tumors on a dog’s paw?

Now that you have an idea of how the vet will arrive at a diagnosis, let’s take a look at three categories of lumps on a dog’s paw. We will start with the scary one, malignant tumors, to get it over with.

1. Malignant tumors on a dog’s paw

Unfortunately, some tumors on a dog’s paw are indeed cancer. These malignant tumors can be locally invasive in some cases. But many of them can also metastasize (spread) to nearby lymph nodes or important internal organs like the lungs.

The most common types of malignant tumors on a dog’s paw include:

- Malignant melanomas

- Mast cell tumors

- Squamous cell carcinomas

- Basal cell carcinomas

- Soft tissue sarcomas

Let’s take a look at each type of cancer individually.

Malignant melanoma

Melanomas originate from pigmented cells in your dog’s skin. The good news is that the majority of these tumors are benign (i.e. melanocytomas). But, in about 10% of cases, the pigment cells can form a malignant melanoma instead.

This seems to happen more often in certain areas like the eyes, mouth, or paw. More specifically, a dog can develop malignant melanoma on the paw skin or paw pad or in the toe or toenail bed. Also, certain dog breeds, like the Scottish Terrier, Irish Setter, and Golden Retriever tend to be at higher risk for malignant melanoma of the paw.

Because they come from pigmented cells, melanomas tend to be a brown or black tumor on your dog’s paw that has a raised or domed appearance. However, there are a few cases where there is no obvious coloring (i.e. amelanotic melanomas). Or, sometimes the tumor may be flat and have indistinct margins. This is why testing any skin bump is so important!

Treatment for melanomas

If your dog has a suspected melanoma that is too small for an FNA, or if the FNA suggests the mass is a melanoma, surgical removal of the mass is typically the next step. Melanomas are a tumor type where the post-surgical biopsy is very important. Not only can it distinguish benign from malignant melanomas, but it can also evaluate the tumor margins.

The goal of surgery is to remove the mass with large margins. This makes it less likely that the malignant melanoma will come back or spread. However, this can be difficult on the foot because there isn’t a lot of extra tissue. Sometimes, if the mass is on the toe or in the toenail, the vet may recommend amputating the entire toe. This sounds extreme, but it helps provide good margins.

When complete surgical removal isn’t an option, the next best treatment may be radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Or, there is also a melanoma vaccine for dogs. It is mostly designed for dogs with oral melanoma but may work for melanoma on a dog’s paw too.

Unfortunately, it is estimated that by the time of diagnosis, the tumor has already spread in 30-40% of cases. And with treatment, the average survival time for malignant melanoma is a little over one year.

Mast cell tumors

Mast cell tumors (MCTs) in dogs are the most common type of skin cancer in dogs. So it would only make sense that they can occur on a dog’s paw.

Unfortunately, MCTs are also one of the most frustrating cancer types. They can appear out of nowhere and look like almost anything! On a dog’s paw, mast cell tumors can occur on the skin or under the skin.

Mast cell tumors can be low-grade and slow-growing or they can be high-grade and very aggressive. Most are solitary lesions that are round, raised, and red. But it is possible to have multiple lesions in some cases, and can they have a variable appearance. Occasionally, a more severely affected dog may show systemic symptoms, such as trouble breathing, poor appetite, weight loss, and vomiting or diarrhea.

Like other masses, an FNA is a good diagnostic starting point. However, poking a mast cell tumor can sometimes result in an allergic reaction. This happens when mast cells release the contents of their histamine-containing granules. Therefore, your vet may recommend giving antihistamines like Benadryl for dogs to decrease the risk of a reaction.

Treatment for mast cell tumors

If the mass is an MCT, surgical removal with wide margins is often the treatment of choice. However, it can be difficult to get sufficiently large margins on a dog’s paw. If the biopsy reveals the margins are incomplete, the vet may recommend amputation or radiation and chemotherapy.

Alternatively, there is also a new treatment, Stelfonta®, which is an intratumoral injection. It can be a great non-surgical option for mast cell tumors on a dog’s paw in some cases.

The exact prognosis for dogs with an MCT can vary significantly. If the tumor is low-grade and completely excised, it is unlikely to come back or cause further issues. But high-grade tumors, or those that are difficult to remove, have a worse prognosis.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Like in humans, squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) on a dog’s paw are thought to be caused by UV damage from frequent exposure to sunlight. Thin-coated dogs, or those with light-colored skin, are most likely to develop an SCC, particularly if they like to sunbathe. Unsurprisingly then, the most common breeds affected by cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma are:

- Pit Bulls

- Dalmatians

- Boxers

- Beagles

SCCs can be reddened and slightly raised, but do not often have a smooth, rounded shape like other tumors. Sometimes they can also be crusted, scaly, and plaque-like in appearance. And since SCCs are malignant, they can occasionally spread to local lymph nodes or to other organs like the lungs. That means you might see enlarged dog lymph nodes, trouble breathing, or other symptoms of cancer like weight loss and inappetence.

Typically, a biopsy of the affected area is the best way to reach a definitive diagnosis. However, the vet may also recommend an FNA of a local lymph node if it is enlarged.

Treatment for squamous cell carcinoma

Surgical removal with wide margins is ideal, although radiation can help if the cancer is inoperable. Chemotherapy isn’t usually effective for squamous cell carcinomas. However, there are a few other treatment options.

A topical ointment called imiquimod has had great success in treating SCC in humans and cats, so it may be an option for dogs. Also, photodynamic therapy, which selectively kills cells exposed to a light-sensitizing agent, and cryotherapy (i.e. killing cancer cells by freezing them) may be effective.

Even though SCCs are malignant, the good news is that they are mostly locally invasive and have a low risk of metastasizing. Local therapy can be curative, and the prognosis is good with treatment. However, it is possible for dogs sensitive to UV damage to develop new SCCs in the future.

Basal cell carcinoma

In general, basal cell tumors can be benign or malignant. Thankfully, the benign type is most common in dogs, and malignant basal cell carcinomas are very rare.

Like melanomas, these tumors are sometimes pigmented or black in color. But other times they may be pink or flesh-colored. Basal cell carcinomas may become ulcerated and are typically a solitary bump or plaque. A combination of hereditary and environmental factors (e.g., sun damage) may play a role in their development.

Even if needle aspirate testing confirms a malignant basal cell tumor on your dog’s paw, the rate of metastasis is very low. Thankfully, surgical removal of the tumor is curative, and the risk of local recurrence is low with good surgical margins. Overall, this malignant skin tumor carries a good prognosis with treatment.

Soft tissue sarcoma

The term “soft tissue sarcoma” encompasses a variety of tumors that come from connective tissues (i.e. fat, muscle, fascia, etc.). They tend to be more common in middle-aged to older large-breed dogs with no particular breed predisposition.

One of the most concerning things about soft tissue sarcomas is that they can look and feel a lot like benign fatty tumors (which we will discuss soon). This is why having your vet perform an FNA on any new mass is so important! (If you need more proof of this, check out an article written by well-known veterinary oncologist Dr. Sue Ettinger entitled, “See Something, Do Something: Why wait? Aspirate!“)

Soft tissue sarcomas are usually slow-growing firm masses that may be moveable or attached to the underlying tissues. And they may occur on or under the skin. While they are typically more likely to be locally invasive, it is possible for soft tissue sarcomas to spread to the lungs.

Like many other types of cancerous skin tumors, surgery is the treatment of choice, and the margins should be wide to decrease the risk of regrowth. This may sometimes mean that amputation, or leaving the surgical site open to heal on its own (rather than suturing it closed) may be necessary to treat a soft tissue sarcoma on a dog’s paw. Alternatively, radiation therapy can be an option for tumors that are difficult to remove or have been incompletely removed.

Overall, the prognosis can be good for dogs with soft tissue sarcoma. However, it depends significantly on how well the surgery (and/or radiation) was able to control tumor growth in the area as well as the grade and size of the soft tissue sarcoma.

2. Benign skin tumors on a dog’s paw

The good news is that some types of tumors on a dog’s paw are benign. This means that they won’t spread to other areas of the body or be locally invasive. And they generally have an excellent prognosis.

Plasmacytomas and histiocytomas

Two common benign skin tumors that may appear on a dog’s paw are histiocytomas and plasmacytomas. Both are typically solitary, pink or red, hairless, and sometimes ulcerated masses. Plasmacytomas tend to occur in older dogs. And histiocytomas usually affect younger dogs (puppies or young adults).

While benign, surgical removal is the treatment of choice for plasmacytomas since they can still become large or ulcerated. However, cryotherapy or radiation are also options for plasmacytomas in areas such as the toe, where surgery is more challenging.

For histiocytomas, no treatment is necessary because they spontaneously resolve after two to three months and almost never return.

Lipomas

Lipomas in dogs are fatty tumors on a dog’s paw which originate from fat below the skin’s surface. This may sound strange because a dog’s paw doesn’t have as much subcutaneous fat as other places on the body. However, it is still possible for a dog to develop a lipoma under the skin near the top of the paw.

Since lipomas are benign and don’t tend to ulcerate or bleed, they usually don’t cause problems for a dog. However, if the lipoma is changing the foot conformation or making it hard for the dog to walk correctly, the vet may recommend surgical removal.

3. Tumor look-alikes

Sometimes a bump can pop up on your dog’s skin that isn’t truly a tumor (i.e. not formed by disordered and uncontrolled abnormal cell growth). These tumor look-alikes can be things like:

Sebaceous cysts

If a dog’s hair follicles or pores become blocked, a sebaceous cyst in dogs may form on the paw. These masses may be on or under the skin and typically have a smooth pink, white, or bluish surface. Sometimes a sebaceous cyst may rupture, releasing a grey to white cheesy material. They can also start bleeding, especially if the dog traumatizes the cyst somehow.

Treatment depends on what the cyst looks like. If it is small and not bothering your dog, your vet may recommend keeping an eye on the cyst (once he or she has performed the FNA to confirm that it is indeed a sebaceous cyst). In other situations, such as when the cyst is inflamed, infected, or keeps breaking open or bleeding, surgical removal is the best option.

Interdigital cysts

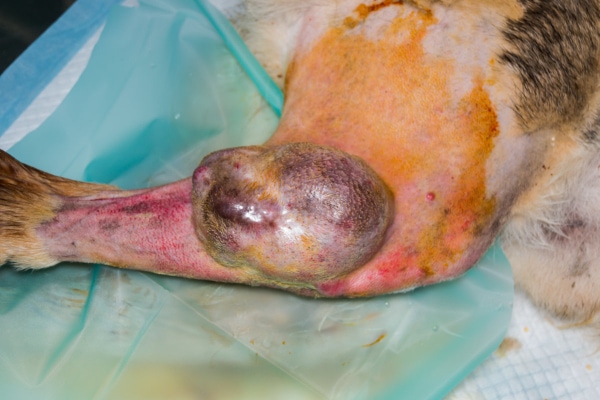

Another paw bump of concern is interdigital cysts in dogs. As the name would imply, they typically form between the dog’s toes. And interdigital cysts are thought to occur when trauma to the hairy skin between the digits leads to irritation, inflammation, and dilation of the hair follicles. The resulting firm, painful, red to purple, itchy nodules can be a solitary lesion, or dogs may have one cyst between each toe. Sometimes these cysts may even rupture and bleed.

Interdigital cysts tend to be most common in large breeds, dogs with wide paws, or those who have other skin conditions like allergies or demodectic mange. Treatment usually involves addressing any concurrent skin disease and infection, plus using anti-itch and anti-inflammatory medications. Surgical removal of the cyst is also an option, but vets typically reserve this for cases that don’t respond well to therapy.

Skin tags

A skin tag is a generalized description of any small, discrete nodule that appears on the skin. They can appear on the tops, sides, and bottoms of a dog’s paws, or even between the toes. Skin tags are seldom bothersome unless they become large and/or ulcerated and infected.

However, cancerous tumors on a dog’s paw can also look like skin tags, so ensure you let your vet perform an FNA on any new or concerning masses rather than chalking them up to “just skin tags.”

As an aside, dog parents can also sometimes mistake an attached and engorged tick for a skin tag. This is understandable because ticks bury their heads in the skin, and their round smooth body can look a lot like a tiny flap of skin.

Foxtails or other foreign objects

Sometimes a new lump on the paw that showed up rapidly may be the body’s reaction to a foreign object lodged in the paw. For example, foxtails in dogs, or other grass awns, can pierce the skin and become lodged between a dog’s toes or paw pads. This can create a painful area of soft tissue swelling which may become red and inflamed.

The veterinarian will often sedate your dog to find and remove the foreign object. Then he or she may prescribe antibiotics to address any infection and pain medications to keep your dog comfortable.

Abscesses

Along the same lines, dogs can also develop a walled-off pocket of pus (i.e. an abscess) on their paw if a puncture wound, or other trauma, seeds the area with bacteria. Typically, an abscess will pop up quickly and may be swollen, painful, warm, and inflamed.

The veterinarian will typically aspirate the swollen area to confirm the presence of bacteria, white blood cells, and purulent debris. This is also a good way to rule out a tumor. Then, depending on the situation, the vet may open and flush the abscess and/or start the dog on pain meds and antibiotics.

Don’t wait and see—do the FNA

After reading the description of all these different tumors (and tumor look-alikes) you can probably better understand why I said that it is difficult to determine if a lump is benign or malignant by its appearance alone. After all, most skin masses are somewhat raised and pink/red or pigmented!

This means it isn’t a good idea to take a “wait and see” approach to lumps and bumps. Especially on a location like a paw where surgery is more challenging due to the lack of extra skin, identifying and removing masses while they are small is the way to go. Plus, the sooner you catch a malignant mass, the less time it has to invade the surrounding tissues or spread to other locations.

Therefore, if you just found a tumor on your dog’s paw, or there is one that has been there for a while without being tested, please make an appointment with your veterinarian. The cost of the FNA and/or biopsy is worth the peace of mind that comes from knowing the identity of the tumor. That information allows you to work with your vet to create a plan to address the tumor. And in the end, that translates to giving your pup a good quality of life for as long as possible.

Did your dog have a tumor on his or her paw?

Please comment below.

My American eskimo started to limp a bit more than a month ago and only 2 weeks ago we found the lump under his paw pad (the vet didn’t see when we first took him for a examination). Long story short, a vet said it looked like a cyst, performed a cytology and saud it was most likely a cyst. She recommended surgical removal. On the day of the surgery, when we brought him home, only upon reading the post op instructions we found out the surgeon amputated ou dog’s toe. Now, questioned about that he said he did it because when the mass is located close/attached to the nailbed 2 out of 3 times it’s cancer. We were shocked with the treatment, the lack of communication, the diference in diagnostic and now we are waiting for the biopsy that we requested, once we learned the surgeon decided to treat it as a malign tumor. i have pictures and videos and would love another opinion.

Dear NB,

I understand your concern and confusion over how things have played out with your pup. I am sorry for the breakdown in communication with your vet and the stress it must have caused. Unfortunately, I am not able to offer specific conclusions or advice just from reviewing pictures and video. Also, at this point the toe has already been removed and I’m not sure what other course of action could be taken. I hope the biopsy results will help to clear things up and offer a diagnosis that can be successfully treated. Praying for answers and a clear path forward. Best wishes to you and your sweet boy.

my dog has a small dark gray lump on the top of of his front paw

Hi Rose,

That definitely sounds like something you should have checked by your veterinarian. Best wishes to you and your pup!

Hey! My golden retriever of 6 years had a black coloured lump like structure on her feet in between the toe nails. I had taken her to a hospital but was told it was not an issue but by the day passes the lump is getting bigger and i am really concerned about this. So it will be a grateful if you give any advice regarding this matter.

Thankyou

Hi Jolly,

I am sorry your pup has this strange lump on her foot that seems to be growing. Unfortunately, without examining her myself, I can’t make specific conclusions or recommendations. It is always ok to get a second opinion. Especially when you have had the issue evaluated by a vet but are left with unanswered questions and lingering concerns. Hoping you can get the answers you need to ensure your girl remains happy and healthy. You are doing a great job advocating for her well-being. Keep up the good work!

Hey my 8 year old german Shepard has a brownish pinkish mass on his right back paw. He does not seem bothered by it but just curios what it could be. It is around the same size of an eos circular cap. Please let me know what you think it is. Thanks!

Hi Adelina,

I understand your concern for your Shepherd and this mass that has appeared on his paw. Unfortunately, without personally examining it, I can’t make specific conclusions or recommendations. Your best bet is to schedule an appointment with your vet and let them do some testing. They can aspirate the lump and get some information by looking at the cells under a microscope. Hoping there will be clear answers as to how you should proceed. Wishing you all the best and praying for a positive outcome.

My 4 year old English Springer Spaniel has a red swollen mass beside her middle nail on her left and on her right front paws. On Friday there was nothing when I filed her nails and on Sunday the mass appeared. I noticed the left mass bled profusely after she was playing. I then took her to the vet on Monday and he has done an aspiration biopsy, which we are waiting for the results. The vet did say there was alot of blood during the aspiration and he hopes he was able to get a good result. It just seems so weird that he happened so fast and also that it is on both paws in the same area?

Hi Francie,

I am sorry your young dog is having issues with these masses on both front paws. I agree it is very strange and am not sure what the cause could be. Was your vet able to get any good information from the cytology sample they sent off for testing? Hoping for definitive answers and a clear path forward. Feel free to leave an update and let us know what you find out.

Hi,

Our 197 pound Great Dane has a large mass in between her toes & the vet says that she would not be able to remove because of being able to stitch together the skin in that area. She put her on pain killers & antibiotics for two weeks. Nothing has changed. The mass has broken through the skin & bleeds terribly. Because it is at the bottom of her foot and walking/jumping, we are constantly changing bandages. They did a fine needle aspiration & couldn’t confirm 100% that was not some type of malignant cells. She just turned seven & the vet said amputation would not be a choice due to her size. We are possibly looking at getting another opinion but have read numerous comments about not being able to remove due to lack of skin. She does not seem to be in pain. Otherwise she is a happy, energetic pup! I wish I could do more for her. 🙁

Hi Deb,

I am sorry your big girl is having issues with this mass between her toes. This location does make surgery very tricky, and I can see why you are concerned and looking for answers. I do think a second opinion would be good, but I highly recommend you ask for a consultation with a specialist. They can give you all the detailed information on testing and treatment options and allow you to make a confident informed decision for your pup. I am glad your girl seems to be feeling well and is still enjoying life. Wishing you all the best as you navigate this unknown path. Feel free to let us know how things are going if you have a chance.

My five-year-old sheep poo has a swollen toe on her his paw. Yvette that I took her to unfortunately did not have the necessary facilities to identify what’s going on. Her opinion is that it could be cancer that he needs to get the toe amputated. I am taking him to a different vet that has x-ray facilities as current vet suggested so that the x-rays can be done and she suggest x-rays of his chest as well. Makes me sad because my little boy is not as happy as he could be.

Dear Melissa,

I am sorry your boy is facing this uncertain future. I am glad you are planning to visit another vet to get some imaging done. Hoping you received favorable results and praying all is well. Feel free to leave an update and let us know what has happened in the last few weeks. Best wishes to you and yours.

my 11 year old miniature poodle has what seems to be an enlarged dew claw. it appears when his dew claws were removed after birth, maybe a digit on his left was not removed completely?? The spot where his dew claw would be on his left paw has always been a bigger bump than his right. It appeared irritated in 2018, swollen for a very short period of time then went down to regular size yet still bigger than right paw. just in the past two months it has become larger and feels solid, not like an abscess. it moved with his digget and does appear to be localized there. we have surgery scheduled to remove the “mass” on March 21, 2024. it is not painful, warm, no discharge and seems to be again surrounding the digit bone that may not have been removed during dew claw removal. No x-rays have been done just waiting on surgery.

Hi Maria,

I am sorry your senior guy is dealing with this odd issue with his dewclaw. I have seen where tissue that was left behind after dewclaw removal started growing a bit of toenail that ended up having to be surgically removed. I am curious to know what your vet will find during the procedure! Praying your boy will do well with anesthesia and make a quick recovery. Feel free to leave an update and let us know how things go. Best wishes to you both!

my 12.5 year old standard poodle has been obsessively licking his back paw and it looks much better after antibiotics. But I have to do xrays because even though the redness and swelling looks better, he is still relentless about licking and biting it. I’m worried that it might be a toenail bed type of cancer because there is not visible lump and his toenail seems to be pushed slightly to the side..

I hope we’ve caught it soon enough. The waiting is killing me.

Hi Susan,

I am sorry your senior guy is dealing with this unknown illness. I understand your concern and think it is good you are planning to pursue other testing options. Hoping the x-rays will offer some answers and there will be a clear path forward. Wishing you both the best!

My 11 y/o Pomeranian has a fleshy mass on the bottom of his paw pad. FNA produced nothing. his hair is falling out, he’s lost several pounds, an area near his throat has turned black. another vet did blood work and even a T4, Low normal thyroid that he feels is not bad enough for meds. They want $4500 to remove the mass and biopsy. But it seems to me that if all these other symptoms are not thyroid related, then a simple cyst or lipoma is not going to cause all these additional symptoms. why pay thousands if cancer can cause these other issues… are they milking me here or is there some truth to cysts causing all these other issues?!

Hi Monet,

I am sorry your little guy is having so many issues and you are left with more questions than answers. Of course, without examining your dog myself, I can’t make specific conclusions, but I don’t think the mass on his paw is related to the other symptoms. If I had to guess, your vet probably doesn’t think the two are related either. The reason for recommending the mass removal is the location. It will be hard to surgically remove the mass and leave enough tissue to completely close the wound/void that is left behind. The longer you wait to have it taken care of allows for the potential that the mass could continue to grow. At a larger size it could prevent your pup from being able to walk and also make removal impossible. I would hate for a benign growth to lead to the end of your dog’s life just because it was allowed to progress for too long. As far as the other symptoms are concerned, it does sound like more investigation may be needed. Has your vet tested your boy for Cushing’s disease? It was just the first thing that came to mind. Here is a link to another article with more information: Cushing’s Disease in Dogs: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Medications

I understand your concern and hope you can find the answers needed to keep moving forward. Wishing you all the best and praying for a positive outcome.

hello. My 17.and a half year old.dog has a pink growth on his front paw. vet tried Clavasepti for 10 cleared up between toes redness.but mass is still geowing some since. it is red/pink. called back today to see next steps. they may want to put him under to remove mass, at 17.5 years old I am a bit worried about putting him under. if it is not cancerous, should I leave it or try and have it removed. would be goodnif they could.freeze and remove without sedation. thoughts. thank you

Hi Joe,

I understand how anesthesia can be scary, especially with a senior pup. But age alone should not be a reason to avoid anesthesia. As long as your dog doesn’t have any other medical concerns that would put him at higher risk, I would recommend you consider surgery as an option. You may not know if this growth is cancerous or not until it is removed and sent to the lab for evaluation. Here are a couple articles with more information:

1. Is My Dog Too Old For Anesthesia?

2. Is My Dog Too Old for Surgery?

Hoping you can get the answers you need to be comfortable with any decision you make for your sweet boy. Wishing you both the best.

Hello!

I think my dog has a tumour on the base of her tail that was ulcerated. It smells and won’t stop bleeding. Her paws are also swollen and won’t stop bleeding – more ulcerated tumours? I took her to the vet a few weeks ago and they gave her antibiotics and gabapentin. Her globulins were high and proteins normal. No liver disease or diabetes either. Not much changed after her medication finished. We are going back in three days for a follow up. Any advice? Thank you!! (She is 11 years old and 5 months; a morkie)

Hi Brittany,

I am sorry your senior girl is suffering with these ulcerated tumors. Unfortunately, without examining her myself it is hard to make specific conclusions and recommendations. With there being several tumors in many locations, it does have me worried that this could be an aggressive form of cancer. Were you able to get your pup in for her recheck with your vet? Hoping you can get some answers quickly and praying for a positive outcome.

My dog is 12 yr old female rottie mix. She has a lump on her lip, the local vet said it’s a cyst but if removed, it could come back. My dog now has a lump on her thumb toe, it’s red, usually seems wet. She licks at it, even tho I try to stop her.

Just tonight I noticed it’s swelled more, I dabbed it with paper towel and it seemed to go down. Any idea,

Hi Kayla,

I understand your concern with this new lump that has appeared on your dog’s dewclaw. Without examining it myself it is hard to make specific conclusions. Since you mentioned it changes in size, I am worried it could be a mast cell tumor. I think it would be best to have your vet check it as soon as possible. They may want to aspirate the lump to get an idea of what kind of cells it contains. I am hopeful you can get some answers and find the best way forward. Wishing you and your pup the best of luck.

My 9yr old lab has a swollen middle toe with weeping lesions and the toenail has fallen out. The vet has told me that it is cancer and is recommending amputation of the toe. She also discovered 3 enlarged lymph nodes and and did a lab test (cytology). some coughing present. If I thought she could have a healthy and normal life for a few more years I’d be okay with treatment. But I worry that it could be a life of recurring pain and repetitive procedures. I don’t want that for me or the dog.

Dear Mark,

I am so sorry your senior Lab is in this tragic situation. I agree, if it seems the cancer has already spread (lymph nodes and/or lungs), then I would probably choose hospice care or euthanasia for my own pup. I hope you can get the answers you need to make a choice with which you can be confident and find peace. Bless you and your sweet girl.

Thank you for this information – very helpful! My Labrador (almost 7 years old) developed a mass on top of her back paw and I had it surgically removed 10 months ago. It was the size of a pea. The biopsy confirmed it was a benign tumor of the follicle (this is how my vet described it). The surgery required intubation. Now, a mass has redeveloped next to the scar from the first surgery. Is this common?

Hi Michele,

Yes, unfortunately this can be common. If a dog is genetically prone to developing a certain type of cyst or mass, then they are likely to have them continue to develop over the course of their life. It is probably just a coincidence that this new tumor is close to where the last one was located. Is your vet recommending surgical removal of this new mass? Hoping this one is also benign, and can be easily managed.

I have a American cocker spaniel who has a tumor on his back toe he is 11 years old and don’t want him to have surgery i would prefer to leave well alone any would appreciate your views

Hi Sandra,

I understand your concern about surgery and your senior dog. It is ok to forgo surgery and choose the path of palliative care if that is what will bring you the most comfort and peace. I usually prefer surgery if I think there is a good chance at a favorable outcome and extended quality and quantity of life. This is not always the case and each dog’s specific circumstances can change what is recommended. With the help of your vet, I hope you can find the answers you need to make the best decision for you and your sweet boy. Wishing you both the best.

My dog is 15 years he has this growth on his paw that smells and bleeding. My vet said it’s a mass, and is infected bc it’s ulcerated. I been to numerous vets. I want to remove but it can only be removed and then treated as a wound because the growth is too large they can’t sew it closed. I attached a picture. Can you give any advice?

Thank you

Danielle

Hi Danielle,

I am sorry you are dealing with this problematic mass on your senior dog’s paw. Unfortunately, the picture did not come through, but even so, I wouldn’t be able to give you specific medical advice without examining your dog myself. I have had situations with my own patients where a mass was too large and did not allow for complete closure after removal. Have you spoken with a specialist? I am not sure what the best course of action would be for your pup. I hope you can find a way to ensure he is happy and pain free. Wishing you all the best. Bless you both.

Great info in this article! I had a dog that was diagnosed with a follicular hamartoma on her paw that we believe occurred because she was wearing boots to increase traction on slick floors. This was before we learned of ToeGrips. Since she needed to walk on slick floors daily, We are so grateful you developed ToeGrips–it made all the difference for us– especially since boots were harmful to her feet.

Hi Sherri,

This makes my heart so happy! I am glad to hear that ToeGrips were able to give your girl the traction she needed to be confident and feel safe in her own house. Thank you for the feedback. Best wishes to you and your pup. ♥

Thank you for your advice I can’t seem to attach the picture. I didn’t do surgery cause I scared he wouldn’t survive. I been cleaning it every day and wrapping it. The growth continues to grow bleed and smell. He eating still. I don’t know if be is in pain. I will leave him alone for now.

Dear Danielle,

It worries me that the growth has a smell. This is usually a sign of dead tissue and/or infection. Even if you cannot pursue surgery, it may be a good idea to have your vet take a look at the wound and possibly prescribe some antibiotics. They can also evaluate your pup’s quality of life and let you know if he is in pain. Keeping you in my thoughts and wishing you the best.

When we adopted Oliver he was kind if puny and had stomach issues. We had tried multiple diets and tried to eliminate allergies. Then when our boy was about a year old he became lame after playing with his best dog friend. He developed 2 small pustules and it was thought that he possibly had a grass awn. Minor surgery was performed and he did not heal as he should have. He ended up with MRSA and we were referred to both GI and Derm. We were able to save his paw (toe) , but a few months later he had a large spontaneous mass develop on his neck. A biopsy was done and he has Sterile Panniculitis. He is well now and will be 5 in October. Just thought you might find this interesting.

Hi Kelly,

That is very interesting! I am sorry Oliver has been through so much over the past 5 years. Glad you were able to get some answers and have a clear path forward. Thank you for sharing your story with our readers. Wishing you and your boy the best for many happy years ahead!

My dog has a sore on paw pad, round red bump, it bled badly & has had it for 15 days, been to vets after it bleeding so badly it would not stop, they bandaged, told no walk, change it every 2 days, bleed is minimal now and on pain relief. Has had 5 vet checkups said continue. My concern is it is not a cut, its a lump like a cyst or corn. Even though bleed is minimal the lump still is so obvious. Surely steroid cream or lump needs to be removed as it will never heal? My dog is a 13yo golden retriever with no other health conditions known. I have pictures before and current.

Hi Melissa,

I am sorry your dog is having so many issues with its foot. I understand why you are concerned and looking for answers. Unfortunately, without examining your dog myself, it is hard to know what to recommend. If you feel like you are not getting the appropriate level of care and attention, it is ok to get a second opinion. Your vet may have been giving the lump time to heal a bit so they can investigate further. Either way, please let your vet know you have lingering concerns and make sure they are aware you are interested in taking the next step with treatment such as surgery. I am hopeful you will find a way to get this issue resolved. Wishing you both the best and praying for a positive outcome.

My 12 year old Golden Retriever had a split toe nail. At first I thought he probably did that jumping off the bed. Then I noticed the split traveling up towards his toe. I took him to the vet and she immediately sent us to a surgeon. They removed the toe and it turned out to be Melanoma. He is now receiving the vaccine treatment.

Hi Martin,

Wow, I am sure that diagnosis was quite a shock. What a blessing you caught it early and your vet acted quickly to have it removed. Hoping the vaccine therapy will be successful and extend your sweet boy’s life. Wishing you both the best for many happy days ahead.