Stomach ulcers in dogs can be painful and sometimes even dangerous. To help you recognize them and know how to help your dog, integrative veterinarian Dr. Julie Buzby explains the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis for stomach ulcers in dogs.

Veterinary school is a pretty high-stress environment. So, it wasn’t exactly shocking when my friend Jill developed a persistent stomachache during finals week. By the end of the week she was doubled over in pain. When we saw her next, we were all shocked to find out that Jill’s severe stomachache was due to a stomach ulcer.

I never forgot how miserable and painful it was for her. It really stuck with me and left me with an extra helping of empathy for all of the beloved doggy patients I have diagnosed with stomach ulcers over my career. The good news though, is that just like my friend, most dogs diagnosed with stomach ulcers respond well to treatment and have a favorable prognosis.

What are stomach ulcers in dogs?

A stomach ulcer (i.e. gastric ulcer) is an area of the stomach lining in which the normal, healthy tissue has been eroded away. All stomach ulcers start out small and superficial, with damage to just the innermost layer of the stomach. Over time, the damaged area becomes inflamed and irritated. And in some cases, the ulcer can eat into the blood supply of the stomach, leading to significant bleeding.

If the damage progresses, the ulcer becomes larger, either in surface area, in depth, or both. As you would expect, the size, depth, and number of ulcers directly relates to the medical seriousness of the situation.

Superficial ulcers of just the innermost mucosal layers are uncomfortable. But they are much less dangerous if they respond to treatment. On the other hand, full thickness ulcers that erode all the way through the stomach, also known as perforating ulcers, are immediate life-threatening emergencies. This is the case because perforating ulcers allow the contents of the GI tract to leak out into the abdomen, causing sepsis. Sadly, perforating stomach ulcers can kill a dog.

Since ulcers can be life-threatening for dogs, it is best to try to catch them earlier rather than later.

What are the symptoms of stomach ulcers in dogs?

Symptoms of stomach ulcers in dogs can be rather vague and non-specific. Some potential signs of stomach ulcers include:

Nausea and vomiting or regurgitation

Dogs with stomach ulcers may vomit or regurgitate. If the vomited or regurgitated material contains either fresh blood or has a coffee-ground appearance due to the presence of digested blood, this is a particularly serious sign of stomach ulcers. And it warrants an immediate trip to see a veterinarian.

Additionally, dogs with stomach ulcers may show signs of nausea such as gagging, salivating profusely, or the dog licking his or her lips.

Decreased appetite

Dogs may lose interest in food due to nausea or discomfort associated with stomach ulcers.

Weight loss

Some conditions cause more chronic ulcers and can be associated with weight loss over time. The weight loss may be related to the underlying condition that caused the ulcer or to the decreased appetite from the ulcer.

Abdominal pain

Dogs with stomach ulcers may show signs of abdominal discomfort or pain such as restlessness, pacing, assuming a praying position, or seeming reluctant to move or lie down.

Black, tarry, or bloody stool

Stomach ulcers can cause gastrointestinal bleeding, resulting in the passage of dark, tarry stools that contain digested blood (i.e. melena). Or, less commonly, the dog may have stools containing bright red blood.

Weakness or lethargy due to anemia

Chronic blood loss from stomach ulcers can lead to anemia in dogs. Signs of anemia include weakness, being a lethargic dog, and pale gums.

Head to the vet if you see symptoms of stomach ulcers

It’s important to note that some dogs with stomach ulcers may only show subtle signs of illness or discomfort. And most dogs with stomach ulcers won’t display all the symptoms on the list.

Plus, since other underlying disease processes are a common cause of ulcers, clinical signs of the primary underlying disease may be present in addition to the signs of a stomach ulcer. And to further complicate matters, the signs on this list can be associated with conditions other than stomach ulcers.

If you suspect your dog may have stomach ulcers based on the presence of any of these symptoms, it’s essential to seek veterinary attention promptly. There can be many causes of ulcers, and the severity varies greatly. Therefore, the sooner the ulcers are diagnosed and treated, the better.

What is the role of stomach acid and GI anatomy in stomach ulcers?

Before we dive into talking about why stomach ulcers form, it is important to understand the role of stomach acid in normal healthy digestion. Inside your dog’s stomach are tiny glands called gastric glands. These glands are responsible for producing stomach acid, also known as hydrochloric acid (HCl).

If you know anything about hydrochloric acid, that might sound scary. My own personal memories of hydrochloric acid involve lots of personal protective equipment and emphatic warnings to use caution during my organic chemistry class. But in the stomach, hydrochloric acid is a vital contributor to healthy digestion. It helps kickstart digestion by breaking food into smaller nutrient building blocks the body can more readily absorb.

The body tightly regulates the production of stomach acid to maintain a balance. Special cells in the stomach monitor the pH levels and adjust gastric acid production accordingly. And acid production isn’t stable through the day, but instead ebbs and flows in accordance with your dog’s mealtimes.

Even with the careful regulation of acid production, you may still be wondering how an acid with as dangerous a reputation as hydrochloric acid can be present inside the stomach without causing damage. This is where GI anatomy and its multiple protective mechanisms come into play.

Layers of the GI tract

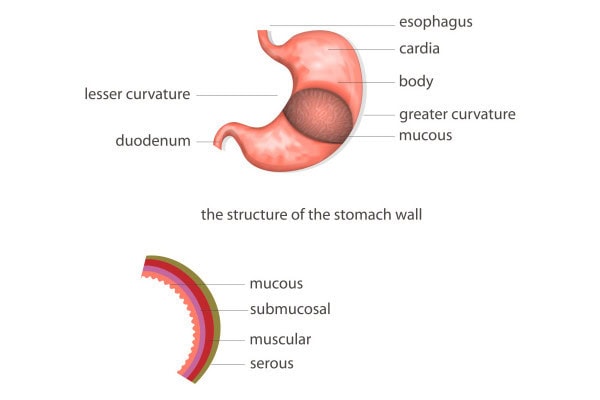

The same four layers make up the entire gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Each layer serves a specific purpose in the digestion and absorption of food. The detailed makeup of the layers differs somewhat based on the location within the GI tract, but the order and name of the layers remains the same throughout.

From innermost to outermost, the layers of the GI tract are:

First (innermost) layer: The mucosa

The innermost layer of the GI tract is called the mucosa. This layer is in direct contact with the food, stomach acid, and digestive enzymes. Specialized cells that produce mucus, enzymes, and other substances essential for both digestion and protection line the mucosa. And it also contains tiny structures called villi and microvilli. These finger-like projections increase the surface area for nutrient absorption.

Second layer: The submucosa

The submucosa contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves. And it serves as a support system for the mucosa. This is also the layer where absorbed nutrients are transported away from the GI tract to other parts of the body to be used for fuel.

Third layer: The muscularis

The muscularis, as the name implies, is the muscular layer responsible for the movement of food through the GI tract. It consists of two layers of muscle that contract and relax in coordinated movements, known as peristalsis. This wave-like motion pushes food through the GI tract.

Fourth (outermost) layer: The serosa

The outermost layer of the GI tract is the serosa. This thin, smooth membrane is composed of connective tissue that covers the entire external surface of the GI tract. The serosa offers extra support and protection.

Each layer works together to facilitate the digestion and absorption of nutrients from food. And all the layers, especially the mucosal barrier, play a role in protecting against gastrointestinal ulcers.

Protective mechanisms in the stomach and upper intestines

The stomach and the first section of the small intestine (i.e. duodenum) are the most acidic areas of the GI tract. And consequently they are the most common locations for GI ulcers. But they also have the most robust mechanisms to protect against damage from the stomach’s potent digestive juices, primarily hydrochloric acid. Some of these protective mechanisms include:

- Mucus—The mucosa, as its name implies, is coated with a thick layer of mucus. This mucous layer acts as a protective barrier, shielding the stomach lining from direct contact with stomach acid and digestive enzymes.

- A built-in antacid—Certain cells in the mucosa also secrete bicarbonate, a natural antacid. It helps neutralize any stomach acid that makes it through the mucus and comes in direct contact with the stomach lining.

- Tightly connected cells—Specialized protein structures called tight junctions carefully connect the cells of the mucosa. These tight junctions create a leak-resistant barrier that prevents stomach acid from getting through the stomach wall and into surrounding tissues.

- Rapid cell turnover—The cells lining the GI tract are some of the most rapidly-dividing cells in the body. This means that new cells can quickly replace any damaged cells, which ensures the integrity of the stomach lining.

- A robust blood supply—The stomach is rich in blood vessels that deliver oxygen and nutrients to the stomach lining. This robust mucosal blood flow quickly clears away any acid that seeps past the protective mucus. And it allows for the rapid cell turnover and repair of any damaged areas.

- Shape shifting—This is perhaps the coolest protective mechanism of all. The epithelial cells lining the stomach can alter their shape to become flatter and more spread out. This allows them to quickly cover any small surface-level defects.

When protective mechanisms fail, stomach ulcers develop

Collectively, these mechanisms protect the stomach and small intestines from the corrosive effects of stomach acid. However, when something compromises these protective mechanisms, the stomach lining becomes more vulnerable to damage from stomach acid. And if the damage goes unchecked, stomach ulcers develop.

What causes stomach ulcers in dogs?

Gastric ulceration in dogs can occur due to a variety of factors. The commonality between them is that they disrupt the delicate balance between the protective mechanisms of the stomach lining and the corrosive effects of stomach acid. Here are some common causes of gastric ulcers in dogs:

Medications

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most commonly implicated cause of gastric ulcers in dogs. Veterinarians frequently use NSAIDs such as carprofen for dogs (Rimadyl®) for their pain relieving and anti-inflammatory properties. They work well, and most dogs don’t have any issues with taking them. However, a small percentage of dogs receiving NSAIDS, especially those with concurrent systemic disease or who are on high doses or a longer course, may develop stomach ulcers.

Additionally, corticosteroids, such as prednisone for dogs, can cause stomach ulcers. These medications have potent anti-inflammatory effects, and can be used to treat a wide variety of medical conditions. Like NSAIDs, corticosteroids can impair the integrity of the stomach lining and predispose dogs to gastric ulcers. Dogs should not take steroids and NSAIDS together because their concurrent administration compounds the risk of gastric ulcer formation.

Cancer

Cancers affecting the GI tract, such as gastric carcinoma, lymphoma in dogs, leiomyoma, and GI stromal tumors can all lead to ulcer formation. They do this by directly compromising the integrity of the stomach lining.

Plus, mast cell tumors in dogs can secrete histamine, a molecule which increases gastric acid secretion. Thus, mast cell tumors increase the risk of stomach ulcer development. Similarly, gastrinomas, a type of neuroendocrine tumor typically found in the pancreas, release gastrin. This is a key gastrointestinal hormone that is responsible for gastric acid secretion. Too much gastrin can also lead to stomach ulcers.

Stress or trauma

Trauma or injury to the stomach lining from swallowing foreign objects or ingesting caustic substances can cause localized damage and ulcer formation. And more generalized trauma that results in shock or low blood pressure can compromise blood flow to the stomach.

Even very strenuous exercise can predispose dogs to developing ulcers. For example, a study on gastritis and gastric ulcers in working dogs reported that 50-70% of unmedicated sled dogs have clinically-significant stomach ulcers after at least one day of a long training run, mid-distance race, or ultra-endurance race.

Systemic diseases

Gastrointestinal diseases like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD in dogs) and pancreatitis in dogs can increase the risk of ulcers. And underlying disease in other organ systems, such as kidney failure in dogs or liver disease in dogs, can indirectly predispose dogs to stomach ulcers. This is the case because these conditions alter the body’s normal metabolic processes that maintain the health and integrity of the gastrointestinal tract.

Infections

Bacterial infections, particularly infections with Helicobacter pylori, have been implicated in the development of ulcers in people. But a link between H. pylori bacteria and ulcers in dogs is less clear cut and more controversial.

Determining the cause of the stomach ulcers is important

Finding and addressing any underlying causes is crucial for effective treatment. Prompt veterinary attention is essential if you suspect your dog may have an ulcer, as early intervention can help alleviate discomfort, speed recovery, and prevent complications.

How are stomach ulcers diagnosed?

If you are concerned that your dog might have a stomach ulcer, your veterinarian will start by performing a thorough physical exam and taking a history. During the exam, you may notice your veterinarian checking your precious pup’s heart rate, gum color, and other dog vital signs. And he or she may palpate your dog’s belly to check for signs of pain or nausea.

While slightly unpleasant for your dog, the vet may also perform a rectal exam. This allows the vet to look for dark or tarry stool which could indicate GI bleeding. The rectal exam is a very worthwhile part of the exam process when there is concern for the presence of an ulcer.

Your veterinarian will also want to know how long any clinical signs have been present. And he or she will probably ask you about your furry family member’s dietary and overall health history. While discussing your dog’s history, it is important to share any recent medications (prescription or over-the-counter) you have administered to your dog.

Blood work

After the examination and history, your veterinarian will probably discuss performing some diagnostic tests. He or she will likely recommend starting with blood tests for dogs. This can be a great way to assess your dog’s overall health and detect any abnormalities, such as anemia or dehydration, which may be indicative of stomach ulcers.

However, patients with ulcers can have chronic, low-grade blood loss that is not overtly apparent on their complete blood count (CBC). So it is important to note that some dogs with stomach ulcers may have completely normal lab work.

Imaging

The next diagnostic step generally involves imaging. X-rays are not very good at detecting stomach ulcers, so abdominal ultrasound tends to be the imaging modality of choice. Ultrasound can sometimes show changes in the stomach wall due to an ulcer. And it can also assess the dog for signs of stomach masses or cancers that increase the risk of ulcers.

If there are concerns about other systemic illnesses, such as inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis, or liver or kidney disease, ultrasound can provide useful information about those conditions too. Finally, ultrasound can help look for fluid or gas in the abdominal cavity that would be evidence of perforating GI ulceration in dogs.

Often, your veterinarian may have a high suspicion of gastric ulcers based on the presence of compatible clinical signs, exam changes, and/or abnormalities on imaging and lab work. This allows him or her to potentially begin treatment without having a definitive diagnosis.

Endoscopy or exploratory surgery

However, if the goal is to reach a definitive diagnosis, the best way to do so is with direct visualization of the stomach or intestinal ulcer. This can be done either during a scoping procedure or when opening up the stomach during an exploratory surgery. These procedures are the gold standard for canine ulcer diagnosis because many times the vet cannot see an ulcer on ultrasound even though one is present.

Endoscopy involves inserting a flexible tube with a camera (i.e. endoscope) into the stomach to look at the stomach lining. This scope is often long enough to reach into the first portion of the small intestine as well.

Exploratory surgery is essentially what it sounds like. The veterinarian will surgically open the dog’s abdomen and carefully evaluate the abdominal contents for any visible or palpable abnormalities.

Endoscopy is less invasive than surgery, but still requires general anesthesia and specialized training for the veterinarian performing the procedure. On the other hand, exploratory surgery is more invasive. But it has the advantage of potentially allowing the vet to surgically remove a perforated ulcer or stomach cancer at the time of diagnosis.

Working from a tentative rather than definitive diagnosis is ok too

Some dog parents make the understandable decision not to pursue these more intensive diagnostics. Instead, they prefer to work with their veterinarian based off a tentative diagnosis. This involves beginning treatment with medications aimed at reducing stomach acid production and protecting the stomach lining. If the dog’s symptoms improve following treatment, it may further support the suspected diagnosis of stomach ulcers.

The good news is that the medications used to treat ulcers are generally quite safe. Yes, diagnostics are important to assess the dog’s overall health and rule out other potential causes of gastrointestinal symptoms. But with a high suspicion of ulcers, you and your veterinarian can pursue empiric therapy without major concerns that the treatment itself will cause further harm.

What is the treatment for stomach ulcers in dogs?

If your veterinarian suspects or confirms that your precious pup has an ulcer, he or she will work closely with you to tailor a treatment plan that best addresses your dog’s specific situation. Generally, the treatment for ulcers is two-fold.

One aspect involves administering a medication that reduces gastric acidity. And the other is supportive care, which is aimed at protecting the stomach lining and addressing any underlying causes. Here’s an overview of the treatment approach your veterinarian might recommend:

Medications to reduce acid production

To decrease acidity in the stomach, your veterinarian will mostly likely put your dog on a proton pump inhibitor or a histamine receptor antagonist.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole for dogs (Prilosec®) or pantoprazole are the most effective medications to decrease acid secretion and treat ulcers. They work by binding to and blocking the receptors needed to create stomach acid.

Histamine (H2) receptor antagonists

Drugs like famotidine (Pepcid®), cimetidine (Tagamet®), or ranitidine (Zantac®) are histamine receptor agonists. Vets may use them to inhibit the secretion of stomach acid and alleviate symptoms. H2 receptor antagonists work by blocking histamine receptors on the cells that line the stomach. This decreases the amount of acid released into the stomach.

You might think that two kinds of antacids would be better than one. But there is no benefit to combining an H2 blocker and a proton pump inhibitor. And this combination may even decrease how well the PPI works, so normally veterinarians pick one or the other.

Medications to protect the stomach lining

Sucralfate (Carafate®) is known as a cytoprotective medication, meaning it protects the cells of the stomach by forming a barrier over ulcerated areas. This promotes healing and can also reduce discomfort and irritation. Sucralfate works best as a liquid slurry and you must give it at a separate time from food or other medications.

Changes to other medications

If a dog with suspected stomach ulcers was on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or corticosteroids, discontinuing these medications or using alternative pain management strategies may be necessary.

General supportive care

The vet may also recommend various other medications or therapies to help your dog feel better.

- Medications to treat nausea and vomiting—The vet may prescribe antiemetic medications like maropitant (Cerenia® for dogs) or ondansetron (Zofran®) to treat vomiting and nausea associated with stomach ulcers.

- Pain medications—Since ulcers are painful, pain medication can be warranted to relieve abdominal discomfort or pain. However, the vet will stay away from NSAIDs due to their link to ulcer formation.

- Intravenous (IV) fluids—The vet may administer IV fluids to dehydrated or vomiting dogs, or dogs who are unable to maintain an adequate fluid intake on their own.

- Appetite simulants and nutritional support—Many dogs affected by stomach ulcers have a decreased appetite. Thus, the vet may add an appetite stimulant for dogs to help encourage them to eat. If appetite stimulants don’t work, then occasionally the dog may need a temporary nasogastric or esophageal feeding tube for ongoing nutritional support.

Addressing the underlying cause

As we have discussed, most ulcers come with some predisposing factor or underlying cause. Identifying and addressing those factors is necessary to hasten recovery, prevent recurrence, and promote long-term quality of life.

Natural treatment for dog stomach ulcers

While I understand the desire to use natural treatments when possible, stomach ulcers can become dangerous and are painful. Thus, following your vet’s advice regarding administering medications like acid-reducers is generally the fastest way to help ulcers heal.

However, there are some things you can do to help support your dog’s digestive system. Bland diets for dogs are great for dogs with digestive ailments because they are easy to digest and gentle on the stomach. Plus, dogs may benefit from probiotics. These “good bacteria” help support healthy digestion.

Additionally, a small amount of plain low-fat yogurt or canned pumpkin for dogs can also sometimes be helpful. Just ensure both of these foods are free of xylitol (i.e. birch sugar), which is toxic to dogs. Only use regular canned pumpkin, not pumpkin pie filling. And keep in mind that not all dogs can digest the lactose in yogurt well, so it could potentially cause some GI upset.

Partnering with your veterinarian

A close working relationship with a veterinarian you trust is so important as you start treating your dog for a stomach ulcer. Treatment requires a comprehensive approach tailored to your individual dog’s needs and underlying causes. So who better to partner with than your vet.

By working closely with your veterinarian to develop and implement an appropriate treatment plan, you are giving your beloved canine companion the very best chance of achieving a successful outcome.

What is the prognosis for stomach ulcers in dogs?

The prognosis for gastrointestinal ulcers in dogs can vary depending on several factors. They include the severity of the ulcers, if the underlying cause is found and able to be treated, and the overall response to treatment.

Generally, the prognosis is favorable for dogs with mild or superficial ulcers that have not penetrated deeply into the stomach or intestinal wall.

Conversely, severe ulcers that have caused significant damage to the GI tract may have a poorer prognosis. This is especially the case if complications such as perforation or hemorrhage occur. Perforation and the resulting sepsis from leakage of GI contents into the abdominal cavity are particularly dangerous complications that necessitate an emergency vet visit and emergency surgery. Unfortunately, these complications also carry a relatively grave prognosis.

The prognosis also hinges on identifying and addressing underlying factors contributing to GI ulcers. For example, if stomach cancer or the advanced stages of kidney disease in dogs cause an ulcer, then the prognosis is worse than if the ulcer was caused by a short-term course of medication that can be discontinued.

Additionally, dogs who are otherwise healthy may have a better prognosis compared to dogs with concurrent medical conditions. And dogs who respond well to treatment have a better prognosis than those who don’t.

For most dogs, ulcers don’t recur. But some dogs may experience chronic or recurrent GI ulcers, especially if underlying predisposing factors are not addressed.

Work with your vet

While you may not have control over your dog’s response to treatment, you can ensure he or she receives all recommended medications. This is a great way to help your dog feel as good as possible as soon as possible. Plus, you should keep up with veterinary check-ups during and after your dog’s stomach ulcer diagnosis. These follow-up visits allow your veterinarian to monitor your dog’s condition and make any necessary adjustment to the treatment plan.

It can be hard to see your dog in pain and not feeling like him or herself. But rest assured, by working with your vet and keeping a close eye on your dog at home, you can give him or her the best chances of recovering well from stomach ulcers and never looking back.

Did your dog have stomach ulcers?

Please share below.

I just want to say thank you for your very informative article.

Hi Stacy,

I am glad you found the article to be helpful and informative. Thank you for the great feedback!

This information was very helpful to me,and very interesting. I learned a lot about the ailments and issues with my dog. Thanks for all the inside tips and fixes.

Hi Teresa,

Thank you for the kind words and positive feedback about the article. Wishing you and your pup all the best!

My 7 year old Rottweiler underwent bilateral TPLO and developed a gastric ulcer from the post op NSAID he was prescribed. We are on week 2 of omeprazole and sucralate and have been giving him canned food. He normally eats a raw diet. He hasn’t vomited for a week until today after having a bit of raw food. At what point can I put him back onto his normal diet? He has probably lost about 10lbs already and I don’t want him to lose anymore weight. Also his nutrition is important for the healing process of his knees.

Thank you for any insight.

Hi Corrinne,

I am sorry your boy is having GI issues since starting NSAIDs after his knee surgeries. I understand your concern about his diet, and I agree that nutrition can play a big role in how the body recovers. It is hard for me to say when it will be ok for him to resume his regular diet. I don’t know if he has developed a sensitivity to something in the raw ingredients or if his body will always require a GI sensitive food moving forward. Each dog is different and there are too many factors to predict if and when this switch will be safe. How are things today? Hoping you have been able to stop the medications and praying the TPLO recovery has gone smoothly. Feel free to leave an update if you have a chance. Best of luck to you and your big guy!

Hi there! My baby was just diagnosed with an ulcer and kidney stones after she threw up blood one morning. We took her to the vet where they gave her some fluids and meds through an IV. We are 3 days out from this happening and have been on the omeprazole and sucralfate. She hasn’t thrown up since and hasn’t had any diarrhea but her stools have been black. Is this a color change Bacău’s do the med? Or is her ulcer still bleeding into her stomach. What can I do to help?

Hi Grace,

I am sorry your pup is dealing with these severe GI issues. Neither of those medications should cause the feces to turn black. I am very worried that this is indeed due to bleeding into the GI tract (probably the ulcer). Please make sure your vet is aware of this new change as they may need to do a follow up exam ASAP. Praying for healing and a positive outcome for your sweet girl. Best of luck to you both!

Hi Dr. Busby,

My 12 year old 15lb boarder terrier has not been feeling well. After multiple visits to the Vet and the Animal Hospital they believe she has stomach ulcers. She had been on NSAIDS for a while so I wonder if that was the cause. She is off that now. She has been on Omeprazole and Sucralfate for the last 2 weeks. She seemed to be doing better but she really has no appetite so it’s been really hard to get her to eat. She will not eat her dog food. Almost everything I have tried doesn’t work so I’m having to give her boiled hamburger and chicken. The boiled chicken stopped working so now I’m trying rotisserie chicken and even lean steak. Do you think that is making it worse? I’m not really sure what to do and I’m concerned that her not eating is going to make this worse.

Hi Denise,

I am sorry your girl is having so much trouble with her stomach. I understand your concern and applaud you for taking such an active role in advocating for her health and well-being. Without examining her myself, it is hard to make conclusions and offer specific recommendations. If you are not already working with a specialist, it may be time to ask your vet for a referral to internal medicine. Also, your pup may need more in-depth testing such as lab work or even an abdominal ultrasound. Hoping you can get the answers you need to get things back on track. Praying for healing for your sweet girl and wishing you all the best.

hi dr. busby,

our sweet little girl, emma, is anemic and has lost some weight. we are 2 weeks into diagnosing and treating her–she is a 6 year old toy poodle. our vet believes she has stomach ulcers, and put her on iron and omeprazole 2 weeks ago. today she added sucralfate (as a liquid slurry) to her treatment regimen. we are hopeful as she does seem to be improving since we started with the meds 2 weeks ago, and her bloodwork was a little better today.

my question centers around your comment that the sucralfate should not be administered with any food or other medications. i asked our vet today (before i found your article tonight) and she said to give the omeprazole and sucralfate together before breakfast, and then just the sucralfate before dinner. i read where the coating that is achieved with the sucralfate can prevent or cause problems with the dog absorbing other medications and that’s why it should be given on its own. does that also apply to omeprazole, or is it ok to give them together in the morning?

lastly, i read that a common side affect of sucralfate is constipation. what’s your advice to combat that if it does become a problem for her?

thank you for your well-written and informative articles. AND for allowing questions and providing answers!

patti & benny

Hi Patti,

I am sorry Emma is having these GI issues and understand your concern for her well-being. From my experience and research, I would always advise my clients to give the sucralfate alone and not combine it with any other medications (including omeprazole). But there may be information available that I am just unaware of that says this combination is ok. If constipation becomes an issue, your vet may recommend a laxative or something as simple as adding a spoonful of pumpkin to your girl’s diet. Hoping she will start to improve and praying for a full recovery.

My 4 yr old Great Pyrenees had a ruptured ulcer. She spent 8 days in the small animal hospital. After an endoscopy, they found multiple ulcers but no underlying cause.

Hi Melissa,

I am sorry your big girl has endured this painful condition. I understand how hard it can be when you are left with more questions than answers despite your vet’s best efforts to get a diagnosis. How is your pup doing today? Hoping the ulcers have resolved and she is back living her best life. Best wishes and take care!